How can one state simultaneously experience more than two months of soaking storms and floods AND desiccating drought and wildfires? Here’s a story about stubborn weather patterns that divided California in half and refused to budge. Part Two (see page 2) explores recent research from the scientists who are trying to explain these recurring weather whiplash anomalies.

We frequently highlight the startling contrasts between the relatively wet slopes and valleys facing the Pacific (cismontane California) versus our true deserts on the continental rain shadow (transmontane) sides of California’s major mountain ranges. Since this is NOT our focus here, you can surf back into our website or check my book to find those stories. In most years, a more gradual transition usually develops between wetter Northern California (closer to the path of winter’s storms) and relatively drier SoCal (where resilient high pressure often veers storm tracks to the north). But as 2024 evolved into 2025, that annual pattern became historically dramatic, as if the ancient mythological Mediterranean Gods Zeus or Jupiter had conspired with Mother Nature to build a massive wall between north and south.

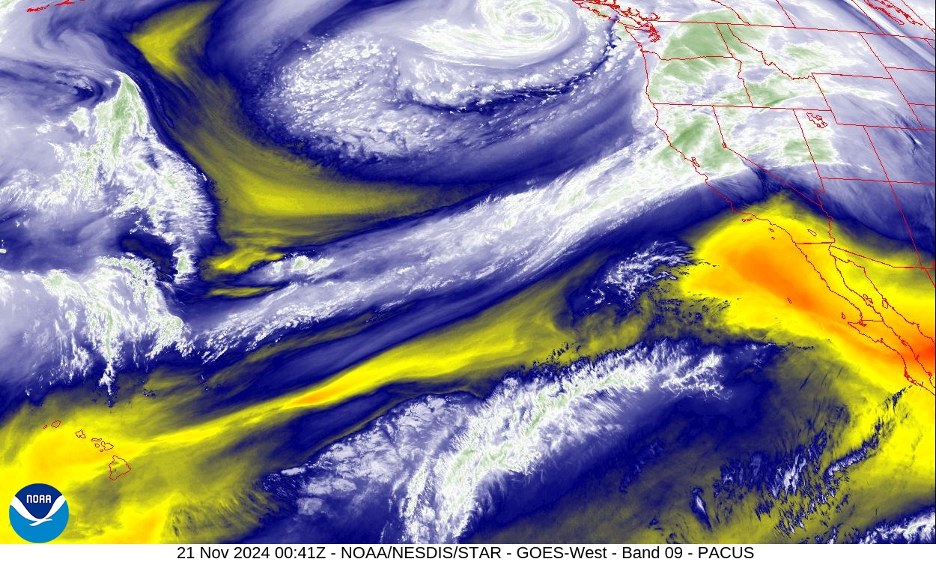

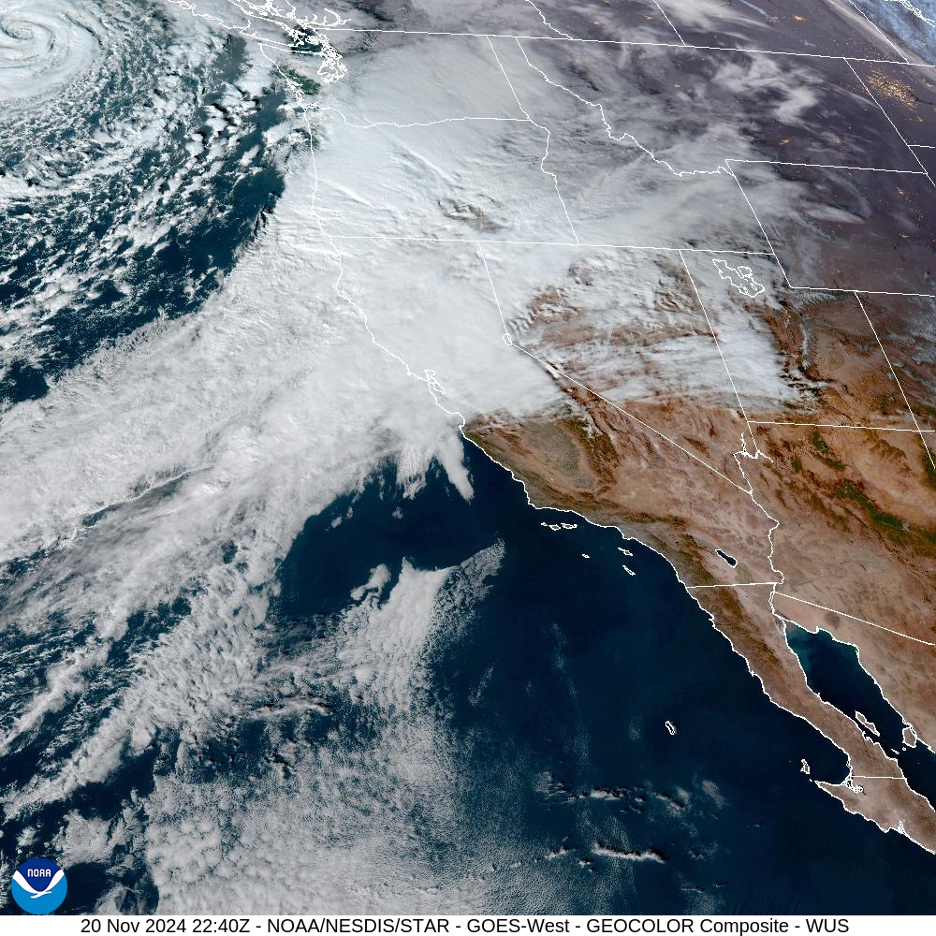

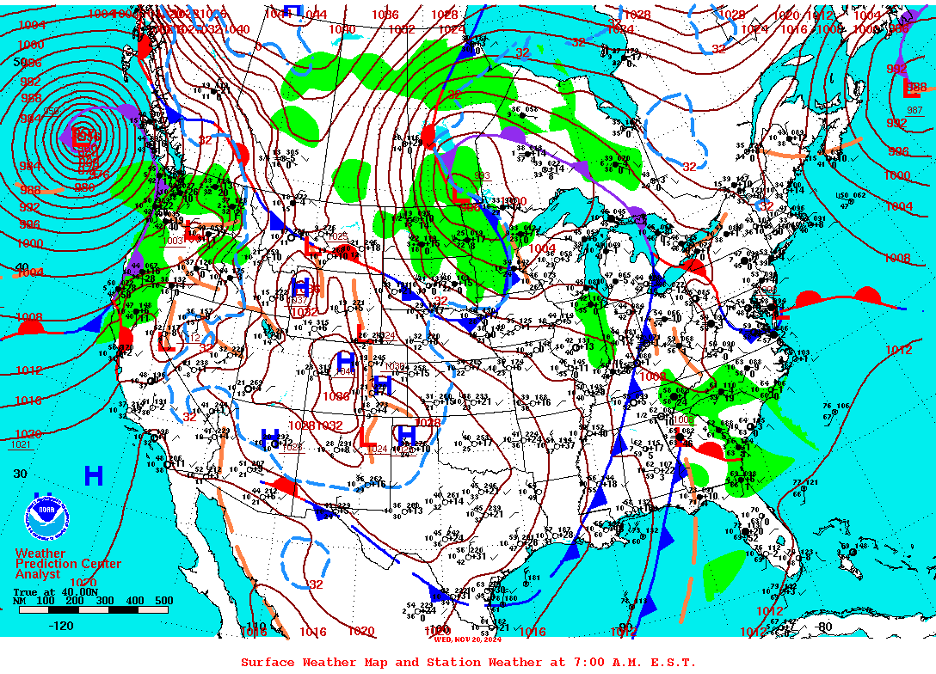

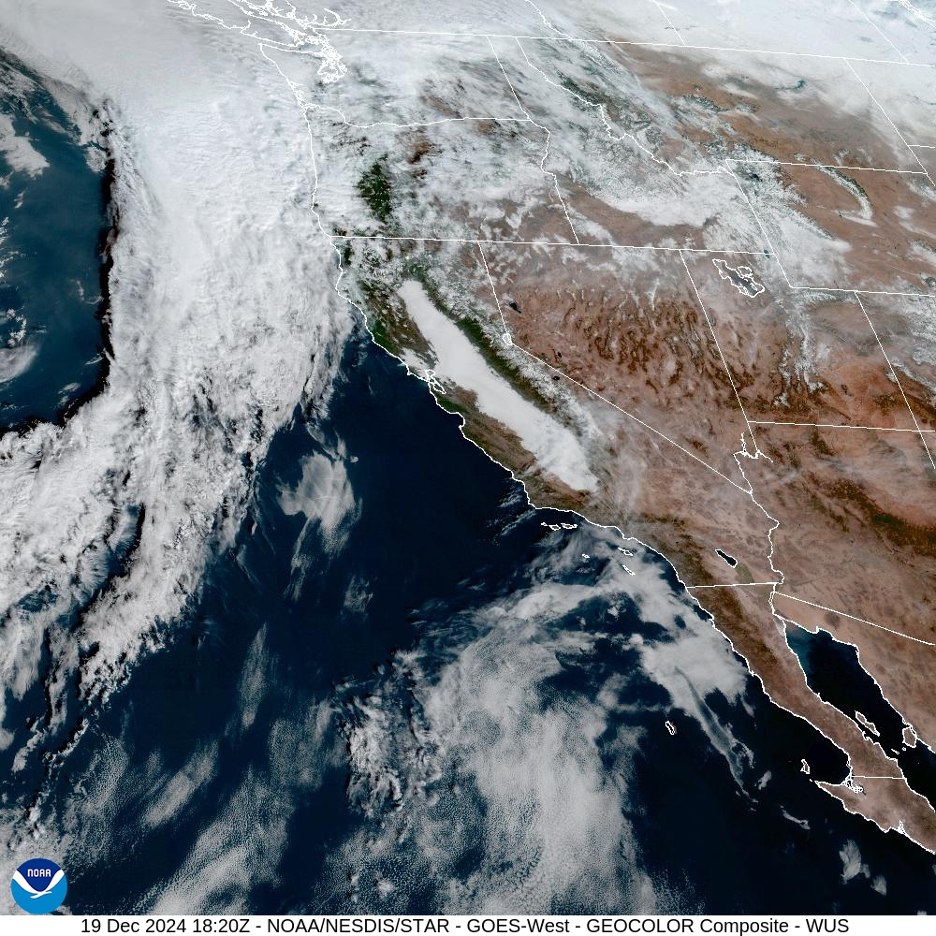

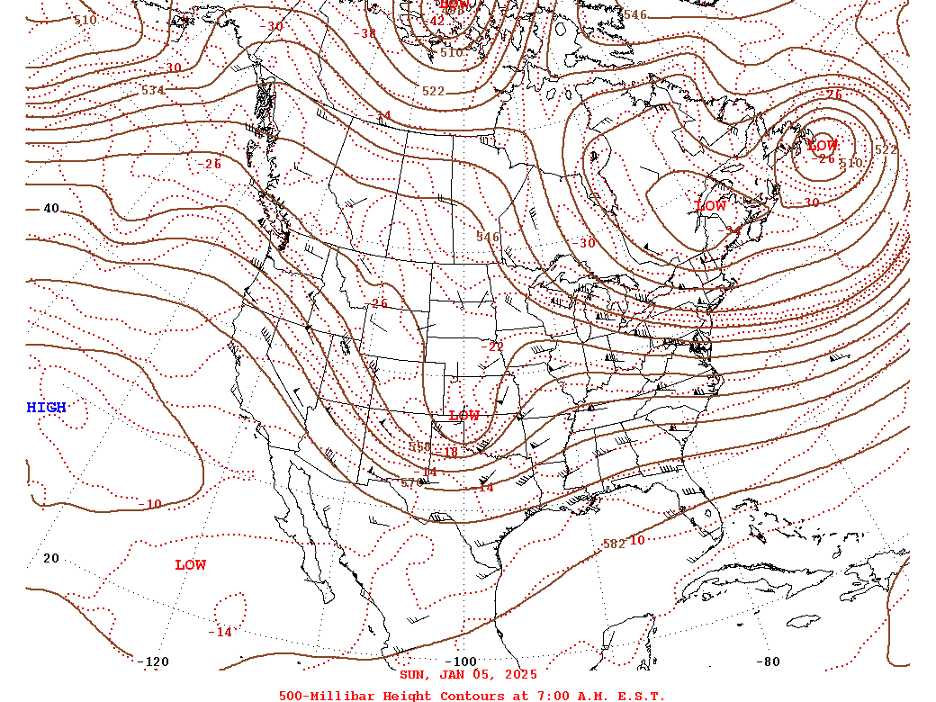

Winter’s rainy season roared in early like a lion in the north, renewing concerns about flooding. But the storms were no-shows in the south, extending summer’s drought and fire season well into the new year. California’s fickle bipolar weather patterns developed in November and December, 2024 and expanded into January. Jet streams, storm tracks, and soaking atmospheric rivers raced off the North Pacific and made their annual gradual migrations into the Pacific Northwest and toward Northern California early in the season. But by the time they crept farther south into Central California, they encountered unseasonably resilient high-pressure ridges that blocked their progress so that storms were instead ejected north and east, leaving Southern California dry under the high.

Late autumn and early winter’s exceptional meteorological boundary between wet Northern and dry Southern California could be drawn roughly along a line from the central coast near Big Sur, then east across the San Joaquin Valley and southern Sierra Nevada. Locations far north of this line, especially up past the Bay Area and near the Oregon Border, were getting clobbered by powerful winter storms that included classic atmospheric river deluges. When an early-season atmospheric river barreled through Northern California and targeted Sonoma County in November, 2024, several weather stations recorded more than one foot of rain in less than three days. But the storms couldn’t penetrate into resistant high pressure that dominated south of our imaginary boundary. From November well into January and the traditional rainy season, weather fronts repeatedly died out as they approached and then navigated the Transverse Ranges, particularly south of Santa Barbara.

As 2024 came to a close, persistent weather forecasts included rain for several consecutive days and even weeks in the north, but fair and dry weather in the south. Though we expect Northern California to easily win in the annual rainy season water wars, this season’s abnormal pattern seemed to be on steroids. By the start of 2025, seasonal rainfall totals (in the three+ months since Oct. 1) ranged from more than 50 inches on Pacific slopes near the Oregon Border to widespread totals of less than 0.25 inches along the Southern California coast. Located on those wet Pacific slopes near Oregon, Gasquet recorded more than 125 inches of rain for the 2024 calendar year, while some SoCal coastal weather stations had accumulated around 1/10th of an inch since the last spring! Weather headlines on the northwest coast emphasized flood stages on local streams and rivers while residents of the south coast were warned of dangerous drought, red flag warnings, and wildfire conditions that threatened well into January.

As if to demand attention, descending air from the resilient high pressure over SoCal was heated by compression to produce widespread temperatures over 80°F in the coastal plains and inland valleys. Here are some example high temperatures on December 18: Oxnard, 87; Ventura, 85; Santa Monica, 82; Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, Long Beach, Pasadena, and Santa Ana all made it to 83°F before that stable and stubborn marine layer reinvaded immediate coastal strips. Mountain resorts (such as the Big Bear station at 6,752’) measured record high temperatures for the middle of December, well into the 60s. Between dry Santa Ana wind events down south, the NWS forecast grew ominous as we approached the middle of our precious rainy season: “… longer range ensemble solutions continue to offer few if any signs for additional rain through at least the middle of January.” That’s when high pressure built over the entire state and at least briefly cut off rain even to the north into mid-January, producing a series of powerful Santa Ana wind events that would fan catastrophic firestorms across Southern California.

As this story is published, no one knows what to expect in the long term during a weak La Niña year in such a climate of change, but precipitation patterns along the West Coast so far are more characteristic of stronger La Niña years. And as if to mock the regional anomalies, official measurements of water content in the Central Sierra Nevada snowpack were near average by January 1, masking the remarkable contrast between the wet north and dry south. Here’s yet another example of how more widespread and equally-distributed beneficial precipitation has become the exception to the more common extremes we have recently experienced across the state. So, what is going on? Click on to Part Two (Page 2) to learn what scientists are discovering and keep your seat belt fastened.