Join us on this field trip into the heart of Central Valley agriculture as we visit two contrasting farms: a small regenerative family farm and then one of the largest agribusinesses in California. We will learn about sustainable farming traditions and the latest cutting-edge scientific research and technologies that power big agriculture.

We all require nutritious meals for our survival. So, the people who grow and harvest our food should be near the top of our list of workers who are rewarded for their labor, right? But that has become wishful thinking as profit margins continue to shrink and more family farms are threatened with bankruptcy each year. Agricultural innovations and revolutions continue to spread, leaving their footprints across California’s landscapes; but current trends too often leave small farmers struggling to pay the bills and keep food on their own tables, all while our popular culture celebrates the latest get-rich-quick millionaires and billionaires who may provide no essential goods or services. California has been the number one agricultural state in the nation for at least seven decades. Our state produces more varieties of farm products than any other state (including some crops that are only grown here commercially), totaling more than 50 billion dollars of income each year.

Disturbing questions and contradictory data ring out from the Golden State and spread to farming communities throughout the country. How are these paradoxical trends affecting life on the farms and our ability to provide healthy, affordable food to the people? What is the future of agriculture as small farms struggle to retain young people who might continue family traditions? Here, we will dive into these controversies and on to the farms to find some answers. We start with a small regenerative family farm and we end with the largest winery in the world, both just outside Turlock in the San Joaquin Valley, between Modesto and Merced. Our guide is Alison McNally, Associate Professor of Geography & Environmental Resources at Cal State University Stanislaus, and this trip is sponsored by the California Geographical Society.

This story is not intended to answer all the questions or solve the many perplexing problems encountered in California’s breadbasket. We have addressed some of them in previous stories on this website and in past publications. For instance, you are probably aware of the controversial debates about how, for decades, big ag has grown at the expense of smaller family farms in California and across much of the nation. Though movements such as farm-to-table encourage sustainable harvests from smaller local farms, many larger agribusinesses have also discovered the economic advantages of more sustainable and/or organic farming on much larger scales. I’ll leave it to you to navigate through the rabbit holes of research and mountains of case studies (such as from UC Davis) that weigh the pros and cons and long-term advantages and disadvantages of small- to large-scale farming. Here, we take you to experience both extremes.

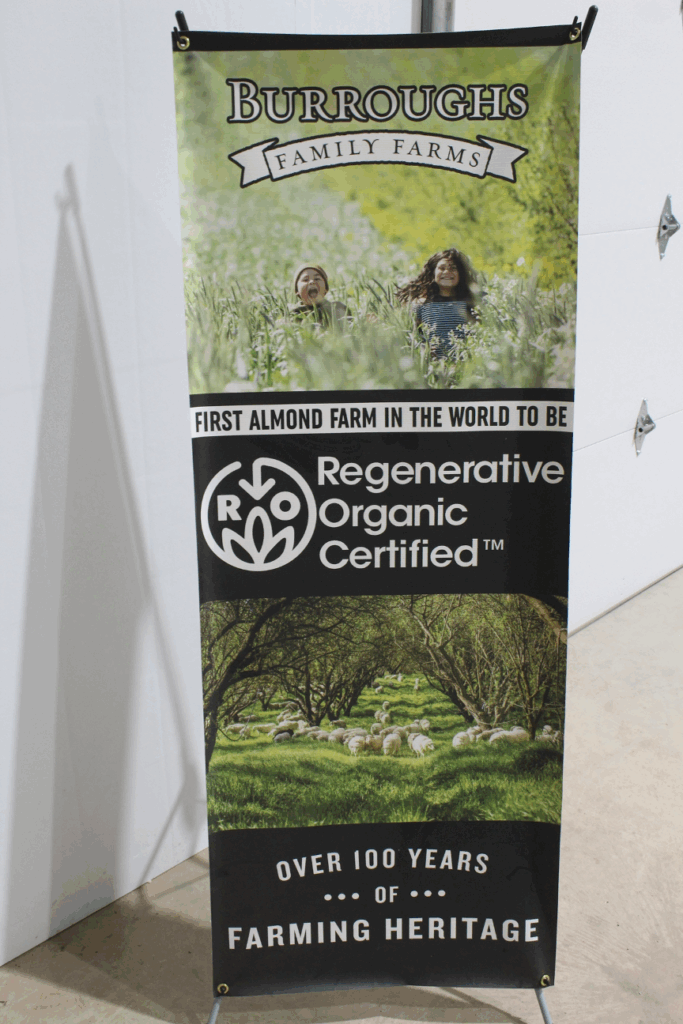

We’re plowing right into the fields for some first-hand experiential learning, guided by the people who work on the farms every day. We start with a morning tour and informative customized hayride through Burroughs Family Farms and we end with an afternoon at E & J Gallo Ranch. There are some surprising connections to our previous story on this website since, on a clear day, you can see some Yosemite National Park high country when you look east from some of these farmlands. And remember the Merced River than runs through Yosemite Valley? It continues downhill to become a water source for Gallo Ranch, after upstream waters are released from Lake McClure to meander into the San Joaquin Valley. And like the previous story, I am using my personal field notes fortified with a bit of background research. All images are originals taken by me with no tampering or manipulation.

Burroughs Family Farms started about 130 years ago in the Berkeley Hills. As Berkeley grew, they paid Burroughs to move toward the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where four dairies were established up to the 1970s. (We are told that Jersey Island, located where the East Bay meets the Delta, was named after their cows.) When the California Department of Water Resources later bought them out, the family conducted a study, which finally landed Burroughs Family Farms just east of Turlock. They became reestablished as a high producing dairy farm, though their dairies have recently shut down within such a punishing market.

This is where we meet Rosie Burroughs. We launch into her world of regenerative practices that emphasize how healthy soils grow better-tasting, more nutritious foods. She immediately repeats a valuable lesson from the movie, Common Ground: “If you take care of the soil, the soil will take care of you.” And from Rosie and the next film she recommends, Symphony of the Soil, we learn that “we don’t grow plants, we grow soil and soil grows plants.” She emphasizes how healthy soils encourage infiltration of rainfall to become giant water-holding sponges that are also more pest-resistant. Such sustainable soil water banks increase productivity while requiring less irrigation, cutting the need for synthetic industrial chemicals that may increase yields in the short term, but poison the land and decrease the quality of yields in the long term.

The Burroughs nurtured 20,000 acres for the three years necessary to convert it to organic farming and they’ve been designated organic for 20 years. Now, they grow almonds, beef, chicken, walnuts, and various other products on 12,000 acres. But too many of California’s small farmers have been forced to become price takers rather than price setters. Rosie tells the story of how big ag pushed them out of the dairy business by undercutting their prices and dominating the market. Another unexpected challenge appeared in the form of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), enacted in 2014, designed to ensure the sustainable use of groundwater resources across the state. The one-size-fits-all act restricts use of protective ground cover due to perceived high transpiration rates. Rosie argues that their ground cover is actually cutting evaporation and protecting surfaces from erosion in the long run, as they use grazing sheep and other natural trimming techniques that return nutrients into the soil: “One of the ways they protect and enhance the soil, air and water is by growing cover crops. Continuous ground cover with alternative crops suppresses weeds, improves soil structure, sequesters carbon and attracts beneficial insects and native pollinators. For organic crop production, it also provides nitrogen in lieu of chemical fertilizers.”

Though they are busy shipping their fresh farm products around the country, Rosie and family were eager to share their expertise and passion for all-in-the-family sustainable regenerative farming, and we were eager to hear more; but we must move on.

It’s time to make the short drive south toward Snelling, where we will learn from farmers who work in what seems to be worlds apart from the Burroughs family … until you look a little closer. This Gallo Ranch was purchased by the Gallo family in the 1970s. Alfalfa and apples have been replaced with rows of grapevines. Their three different acreages in this region (Livingston, Merced, and Turlock) are enormous compared to Burroughs Family Farm, as these landscapes and farming economies define volume-scale winemaking. Founded in 1933 by Ernest and Julio Gallo, their family-owned company became the world’s largest winery, recently raking in revenues of more than $5 billion/year with a total net worth more than $12 billion.

Brent Sams is waiting for us. Brent has been working for Gallo as a viticulture research scientist since 2012. He earned his BA and MA in Geography and his Ph.D. in horticulture and has been researching to understand how fruit chemistry (and quality) changes over time and space. He has used field measurements to test fruit and light exposure, canopy temperature, and soil cores, sensors to measure electric conductivity and elevation mapping, and remote sensing from satellite, unmanned aerial aircraft, and commercial aircraft. It’s a high-tech GPS/GIS environment where updated yields/acre maps illustrate resources put in versus yield coming out. We noted how Gallo employs around 25-30 Ph.D. research scientists on farms scattered around California and beyond. Add paid environmental science internship opportunities. And since Gallo owns only 10-20% of its supply, Sams works with many other farmers who sell to Gallo. In addition to 100 different kinds of wines from around the world, they also sell juice and color concentrates.

We also met Gallo’s “smart” autonomous tractor. This $60,000 investment exemplifies (with an exclamation point) how farming is changing fast in California. Turn it on, put it into gear, and the rest is done remotely, sometimes throughout the night. It becomes obvious that, with fewer farmers and more scientists and automation, this is NOT your grandparents’ family farm.

Like Burroughs Family Farms, Gallo uses drip irrigation, but this ranch is also well situated with riparian rights and prior appropriation water from the nearby Merced River. They also plant and occasionally cut nitrogen-fixing ground cover, but they don’t rely on groundwater sources here. Water reigns king as each vine requires between 10-20 gallons/week, and even more during heatwaves. Pumps are only capable of pushing water through about ¼-mile of drip lines at a time.

The calendar is also king on these farms. Pruning season peaks during cold and damp January and February and the harvest season runs through August, September, and October, but that has been changing throughout California. Brent provides evidence of the impacts of climate change. Harvest seasons have been getting earlier as grapes ripen faster in higher temperatures. Varieties that require cold nights and big swings in diurnal temperatures have been moving north. Recent extended extreme heat waves are also impacting harvests. So, you might appreciate how the orientation of these rows of grapevines can determine the difference between harvest successes and failures. Rows in California are usually oriented north-south to expose the plants and grapes to just the right balance of sunlight, temperature, and humidity as sun angles change throughout the day. (Hilly terrain, such as in the Napa-Sonoma region, often presents exceptional challenges to these industry norms.) The result is an orderly, repetitious, monoculture landscape that contrasts with the diversity imagined on traditional American family farms.

In contrast to some big ag stereotypes, Gallo has demonstrated it is in this for the long run; they’ve invested in a range of sustainable farming methods that regularly win awards and polish their public reputation. And why not be proud of it? Here are some brief excerpts from their website: “As a family-owned company, GALLO has kept sustainable practices as one of our core values since 1933. Our commitment to our founders’ vision has expanded to not only protecting our land for future generations, but also improving the quality of life of our employees, and enhancing the communities where we work and live.”

And from the Gallo Sustainability Impact Report, “At Gallo, we are leaders in sustainability through our enduring commitment to environmental, social, and economic practices so that future generations may flourish.”… “All of the Winery’s coastal vineyards participate in a unique land management plan started by the co-founders where for every acre of land planted in vineyard, one acre of property is set aside to help protect and enhance wildlife habitat. … E. & J. Gallo Winery has led the way in developing and refining new environmentally friendly practices such as minimizing the use of synthetic chemicals, fertilizers and pesticides, recycling and reusing processed water, creating new wetlands and protecting existing riparian habitats.” Perhaps Gallo has more in common with Burroughs Family Farms than we may have originally thought.

Whether from a small family farm or big ag, much of our food and drink is produced in the Central Valley. These field experiences into the heart of the valley help us appreciate the work that goes into growing and harvesting what we take for granted, and in decoding the lasting imprints these people and their industries leave on our landscapes, economies, and cultures.

A big thanks goes to Professor Alison McNally for organizing and leading the field trip. Other leaders at Cal State University Stanislaus (such as Professor, Department Chair, and CGS President Peggy Hauselt and professor and former CGS President Jennifer Helzer) worked to make the conference such a success. I am forever indebted to the professionals in the California Geographical Society for championing more than three decades of action-packed scholarly conferences that have informed my teaching and writing, including so many stories on this website. This year, I am particularly grateful for receiving their prestigious Outstanding Educator Award for 2025. After four decades of research, teaching, writing, and putting my heart into such a rewarding profession, this unforgettable conference was icing on my career cake. Thanks to all!

Here are additional sources for those interested in regenerative agriculture:

Sustainable Harvest International

Alison Mcnally also sent these sources recommended by Rosie:

Common Ground – https://commongroundfilm.org/ streaming on Amazon – a follow up to the film “Kiss the Ground”, Common Ground takes a look at regenerative agriculture and the importance of it as an alternative to conventional agriculture. Some of the footage was taken at Burroughs Family Farms.

TED talk featuring Dr. Jonathan Ludgren (founder and director of Ecdysis Foundation) (13 minutes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=okgGmohpaJQ –

Finally, another Alison recommendation: Jean-Martin Bauer, who has managed food programs and worked as a food security analyst for the United Nations World Food Programme around the globe, is the author of The New Breadline: Hunger and Hope in the Twenty-First Century.

THE END