Day Five (Wednesday, 4-16-2025): Following the Trail to Native Americans and American Settlers

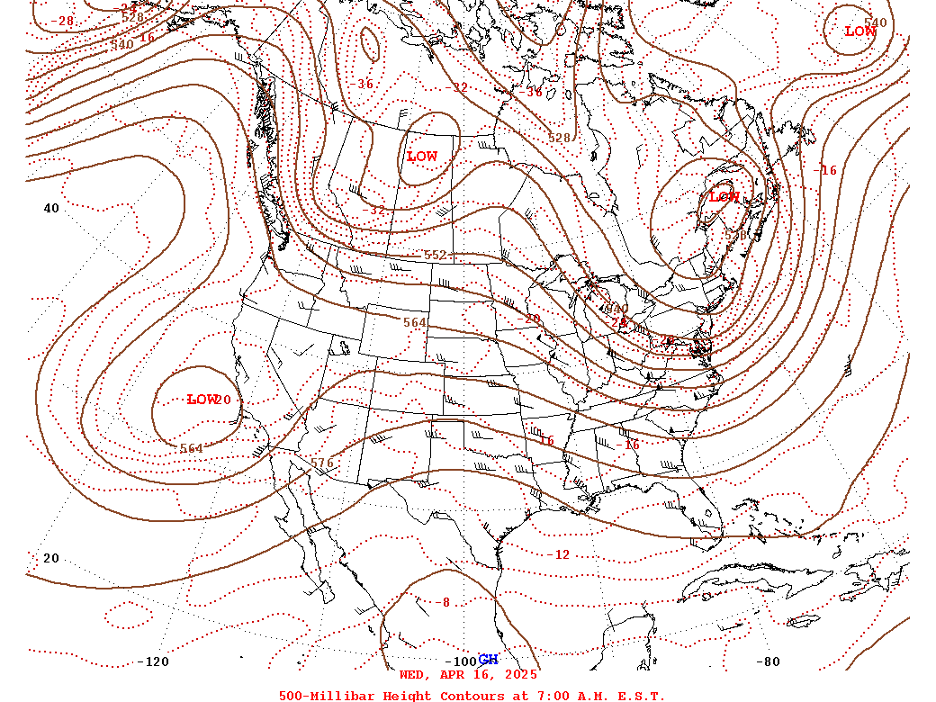

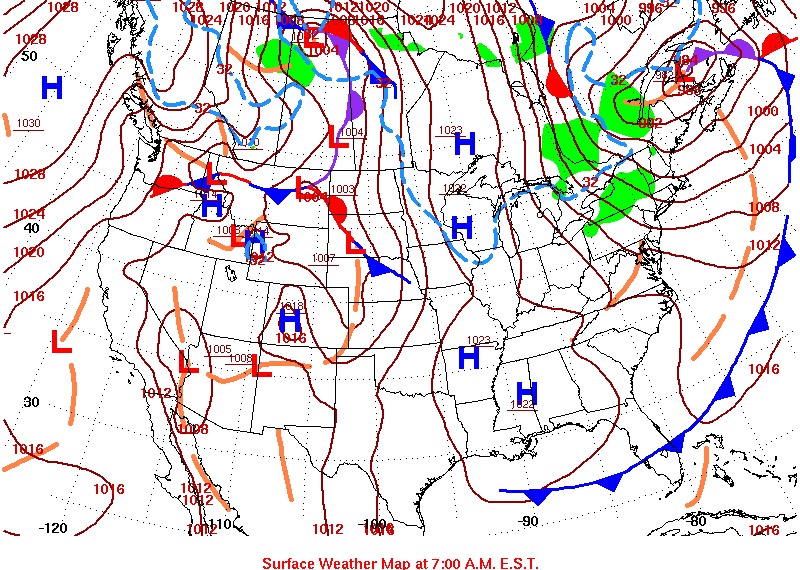

Today, we focus on Yosemite’s human history. But first, that pesky upper-level low that cut off from the general circulation pattern to spin off the coast days ago has finally drifted toward us. Instead of introducing instability that would normally ignite afternoon thunderstorms over the mountains this time of year, it gently ushers in low-level moisture that blocks surface heating. As the day progresses, the cool, misty weather pattern begins to resemble thick marine layers so common to California’s coastal regions, where many of our fellow students and other visitors to these parts live.

During our final meandering return trip to Yosemite Valley, we get an informative earful from Chris and then another treat when Yosemite guide and fellow student Britain Peters takes over with a chronological play-by-play recalling people in Yosemite. He narrates for those “Green Dragons” that snake their way through Yosemite, carrying visitors hungry for some history that could help explain these spectacular landscapes. Here are just a few select stories from Britain and my field notes.

Native Americans have lived in Yosemite Valley for at least 4,000 years. Mortars and pestles (grinding stones) used to pound and grind acorns, seeds, and nuts have been found with organic residue that can be dated. (We will respect the “nothing about us without us” slogan by learning from a Native American park ranger later in the day.) The first confirmed “discovery” of Yosemite Valley by European Americans was in 1851, when the valley was described as resembling a “park”. This is likely due to the occasional controlled burns that kept valley meadows clear of encroaching conifers.

A cast of early Yosemite characters included the likes of businessman James Mason Hutchings, who arrived in California during the Gold Rush. He organized the first recreational trip to Yosemite Valley in 1855, when he started promoting the valley. By 1864, James and his wife, Elvira Hutchings, were operating their hotel there, the Hutchings House. James Lamon, who also arrived in California during the Gold Rush, purchased a land claim on the east end of the valley, built a cabin, and planted an apple orchard (for livestock, pies, and cider) and garden. He is believed to be the first settler to stay throughout the winter (during the early 1860s). The apple trees you see around Curry Village have survived as a part of Yosemite history. The first chapel in Yosemite (now the oldest building in the valley) was built in in the 1870s. Though it was moved, it is still a tourist attraction, just a short walk from the main valley road. In 1899, the Curry Family started a concession of seven tents (rented for $2/day) that welcomed 29 visitors during the first year. It eventually grew into today’s Curry Village.

Esteemed state geologist and acclaimed conservationist Josiah Whitney surveyed across the Sierra Nevada and California during the 1860s and advocated to set Yosemite aside as a park. He became a pioneer and champion of geology with his research and publications about the Golden State. But he would eventually get into a dispute with naturalist John Muir (who arrived in 1868 and returned many other times) about how the valley was formed. Muir correctly understood that parts of Yosemite were carved by large glaciers and that a few small glaciers remained active. After years of ridiculing Muir, Whitney died in 1896, never admitting that he was wrong in believing that “the bottom of the Valley sank down” and that Muir was right about the glacial topography.

By the 1870s, rock climbers had conquered several routes that included Half Dome. Yosemite has been a hub for rock climbers ever since, even helping to inspire companies such as Patagonia. (Today, it takes an average of 3-6 days to climb El Capitan, but the record is just less than 2 hours.) An average of more than two rock climbers are killed in the park each year and more than 100 rock climbing accidents, including serious injuries, are also reported.

Thanks to the work of naturalists such as John Muir, Yosemite was designated a national park in 1890, making it our third national park after Yellowstone (1872) and Sequoia (1890). In 1903, Muir guided President Theodore Roosevelt through the Yosemite wilderness, stopping at the Mariposa Grove, Sentinel Dome, Glacier Point, and Yosemite Valley during three days of travel and camping, inspiring the president to set more lands aside for protection.

One unfortunate stain in Yosemite history involves the storied bears. Relatively unpredictable and aggressive Grizzly Bears (Ursus arctos) were exterminated in California by the early 1900s. This left extensive habitat for the smaller and more docile Black Bears (Ursus americanus). During the first half of the 20th Century, bears were encouraged to gather around fresh garbage dumps in the park to entertain tourists in circus-like settings that guaranteed each visitor a view of bear behavior. But as the bears and their offspring became more comfortable around humans, they also lost their wild instincts, learning that humans carried tasty, high-energy food. Bear encounters grew more dangerous and chaotic, requiring park rangers to euthanize problem bears. By the 1970s, all dumps had been removed from the park. Efforts to bear–proof camp grounds, parking lots, and infrastructure in the park and to educate tourists have been successful so that there are fewer bear-human encounters, bears remain wild (and alive), and visitors are safer. Today’s accomplished naturalist knows what I always taught my field students, some who had been inaccurately indoctrinated to fear nature: that the average number of people attacked and killed by wild animals in California is less than one each year; and that includes sharks, but not incidents such as domesticated dog attacks, car versus deer accidents, multiple bee stings, etc.

It’s time for a hike past the end of the road to Happy Islesand beyond for those who are faster and more energetic. Here at our Curry Village trailhead, another staged event was celebrated each summer evening until the 1960s: the world-famous Yosemite Firefall. Smoldering embers were prepared up on Glacier Point (directly above). As the gathering crowd became silent, a voice from thousands of feet below called, “Hello Glacier Point … Is the fire ready?” A distant call from above was heard: “The fire is ready!”, followed by, “Let the Fire Fall!” For several minutes, a ribbon of flaming coals plunged more than 3,000 feet down the granitic cliffs, to the delight of the crowd below, as if humans were trying to prove that they could possibly make the Yosemite experience more spectacular. This is also the site of the 2008 rockfall that buried parts of Curry Village and left giant boulders scattered about. Efforts to move facilities out of harm’s way have been successful so far, as summarized in our notes from a few days earlier.

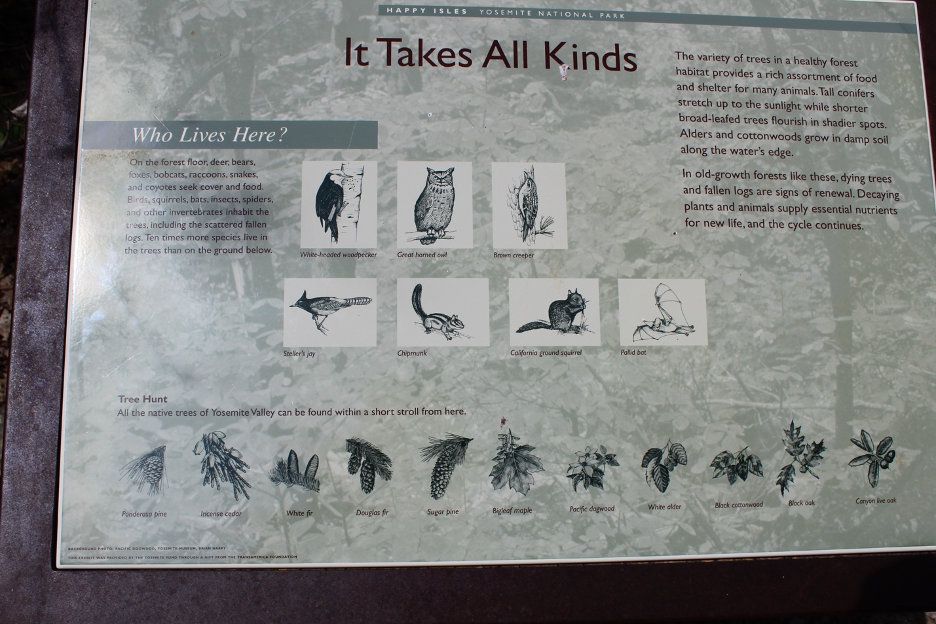

Along the trail to Happy Isles, we use iNaturalist and AI to identify two common shrubs that attract our attention: “In Yosemite, gooseberries and mountain pink currants, both members of the Ribes genus, are easily distinguished. Gooseberries typically have thorny stems and larger berries, while mountain pink currants have smooth stems and smaller, more delicate berries with pink or reddish flowers.” Near Happy Isles, we also learn how Fenway Park in Boston (the infamous MLB baseball park with the Green Monster wall in left field) was built in the Fenway neighborhood, which was filled in over a marshy area, or “fen”. Look for the names of other natural features that remain imprinted even in our most crowded urban environments; you should find plenty of examples in your neighborhood. Along the trail around this Yosemite fen, you might notice bigleaf maple, white alder, black cottonwood, black oak, and canyon live oak. Such reliable water sources create riparian environments that help to accelerate decomposition so that nutrients are returned and recycled without the need for fire.

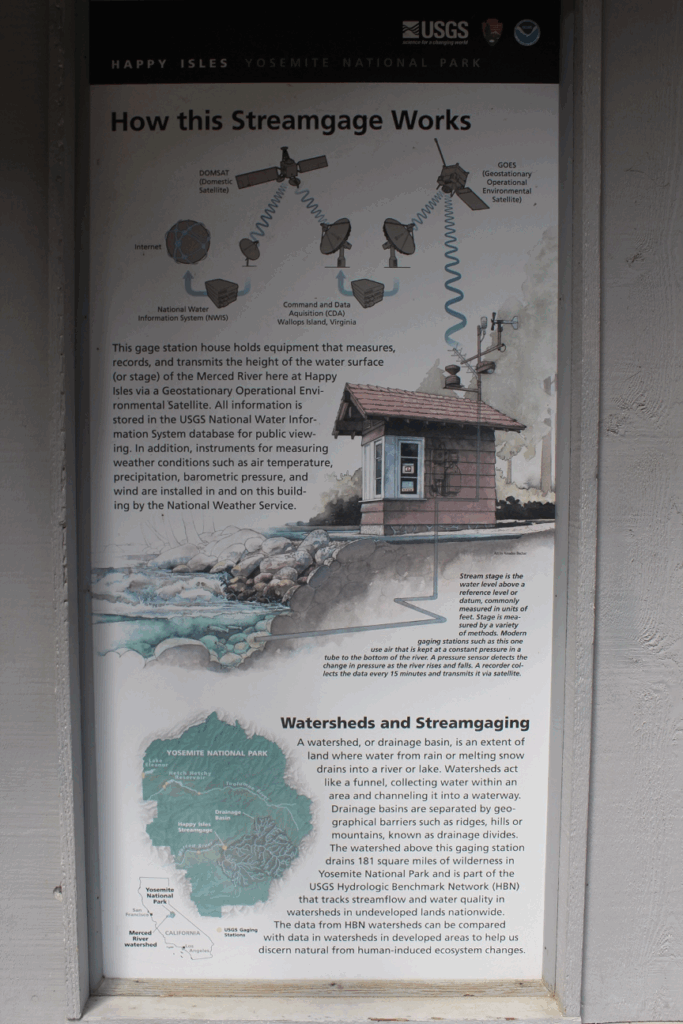

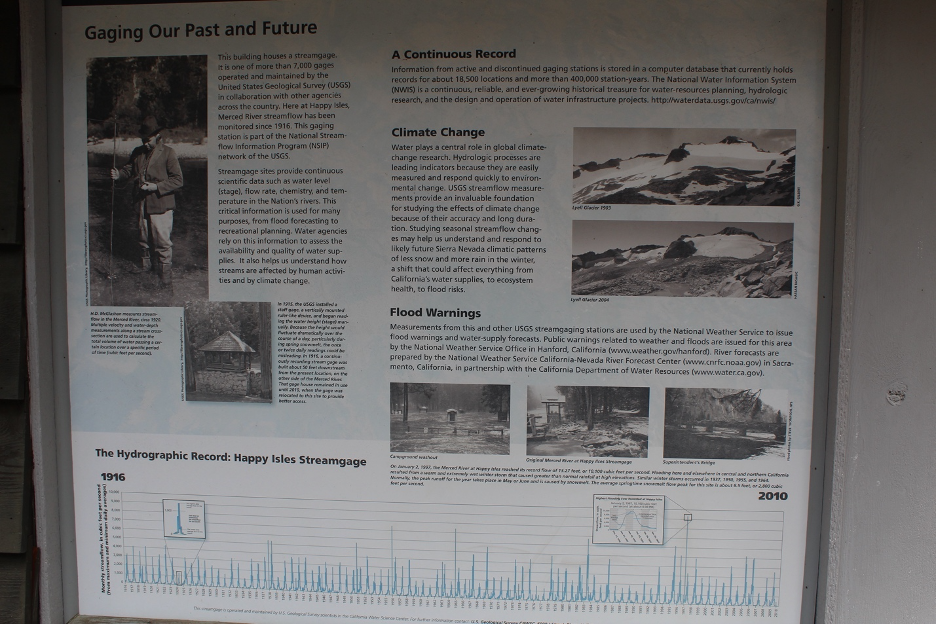

This popular and often overcrowded trail leads us to the Happy Isles Visitors Center, open today, thanks to Yosemite Conservancy volunteers. The trail eventually climbs up to the accessible hanging valleys and switchbacks at Vernal Fall and then Nevada Fall. It’s also the infamous trail I’ve taken to the top of Half Dome. That exhausting but exhilarating longer, round trip strenuous route requires a full day from early morning to sunset, and a lot of energy. The trail to the top also becomes untraversable when there is ice and snow and is to be avoided during periods of summer afternoon thunderstorms. In recent years, the final leg up the “gentler” face of Half Dome (with the chained steps) requires a permit. Hikers, surprised by pop-up thunderstorms, have been slipped and fallen to their deaths during desperate attempts to scamper down the steps to safety. Here’s another reason why a savvy naturalist must also be experienced and skilled at weather observation and interpretation. The crowded Yosemite shuttle will take us back into Yosemite Village for lunch.

We meet at the Yosemite Museum, which is the primary Native American Museum in Yosemite. Visitors learn about the Ahwahneechee people who lived in the valley, and the Miwok and Paiute people, who lived in surrounding regions. There is a re-created Indian Village in the back of the museum. Here is also where we meet Ranger Ben Cunningham-Summerfield. In that spirit of “nothing about us without us”, Ranger Ben shares some of his traditional ecological knowledge and research, passed down by the Miwok and Piute people who lived in this region for thousands of years.

Plants on display at the demonstration village range from the foothills to higher elevations; each species has specific uses that helped sustain these hunter-gatherer cultures. Note that, except for along the Colorado River, California Native Americans didn’t practice agriculture, probably because it wasn’t necessary for their survival. But they did encourage, nurture, and manipulate particular species and plant communities that they found most valuable. Native plants were used as insect repellants, sinus cleaners, stew pots, and acorn stores (known as “chukahs” or granaries). Soap root is a bulb in the yucca family that was baked to eat and also used to make pastes and glues. Acorns from various oak species (such as black oak, blue oak, canyon live oak, and interior live oak) were ground up into a flower and leached (to remove bitter tannins) as vital staple foods. In foothill communities at lower elevations, California buckeye was cooked and processed similar to acorns. This classic film shows how a Nisenan woman prepared buckeye. Leaves and berries of the creeping snowberry were harvested for food and medicines. Parts of creek dogwood were used to make baskets, dyes, and medicines. The flexible half of cedar limbs were used to make bows and arrows. Ranger Ben then demonstrated (with impressive accuracy) how the Miwok hunted with atlatls (spear throwers).

It’s time to return to our ECCO home for dinner. That little upper-level low has drifted nearby to gain control of our weather. Instead of instability and afternoon thunder, the little storm ushers in a deep moist layer of low stratocumulus. A cool, dark, misty high fog eventually seals in the valley and blocks our views of the surrounding cliffs. On our way out of the valley (our last time for this program), we pass disappointed tourists and other visitors looking into a wall of fog at the famous must stop Tunnel View. What begins to resemble gray winter weather will last for two days and nights. At ECCO that evening, we are encouraged to demonstrate how we used iNaturalist to share our discoveries as citizen scientists.

Click (below) to the next page and day.