They’ve lived for thousands of years. They’re the tallest and largest trees on Earth. And now these majestic giants are burning. Follow me as I guide you through California’s endemic redwood forests to learn how they might recover—or perish—following unprecedented wildfires.

Fire has been our friend for millennia. Humans have enjoyed the benefits of controlled fires used to cook our food, heat our spaces, comfort us as we sat around our campfires, provide light and protection, clear and manage landscapes, burn waste, and power our engines. By contrast, many of us have also been terrorized by the unforgettable life-and-death experience of getting too close to an out-of-control blaze. That’s when capricious fire can be likened to an unpredictable vicious predator that breaks out of its cage, or a scene from one of those Jurassic Park movies when Tyrannosaurus rex crashes through its confining barriers. Suddenly, anything goes and we are at the mercy of what we thought we had under our control. Fire is another example of how the very nature that nurtures us can suddenly morph into the misadventure or calamity that kills us. Humans’ relationship with fire has always been complex, but it would be difficult to imagine a place where this partnership has been more misunderstood, abused, researched, and reevaluated, than in California during the last several decades.

During the 20th Century, we began to better understand how wildfires play such vital roles in shaping our Mediterranean ecosystems and landscapes. We reluctantly acknowledged that they must occasionally and necessarily revisit our grasslands, woodlands, and even some forests, and how Native Americans, for thousands of years, encouraged fire’s eminence with their control burns. Until the late 1900s, much of the timber industry and some environmentalists ignored these realities, especially in our most cherished forests that include ancient redwoods. After all, forest fires can destroy beautiful trees and valuable timber destined to become forest products. The infernos kill precious wildlife and leave ugly open scars and charred landscapes that remind us of fire’s terror, death, and destruction. But we now better understand how, even in our redwood forests, wildfires establish delicate successional cycles, balances that must be maintained if California’s ecosystems are to survive and prosper.

We can’t be blamed for the obsessive love we have shown for what remains of redwoods that weren’t cut down and sent to the mills. (Less than 5% of our old-growth coast redwood forests were spared from the saws.) California’s two redwood species represent the largest and tallest trees on Earth. On the surface, these majestic forests appear to be the last places where you would expect, much less want, to see a fire. So, we did our best to keep fire away from these stately behemoths that can grow to more than 2,000 years old. But it was fire suppression and other human interference (such as the introduction of volatile nonnatives) that set the stage for recent unprecedented conflagrations in California forests. The megadrought that extended through the first two decades of this century (enhanced by climate change on steroids) provided the blowtorch on landscapes with abundant accumulated fuel to burn. Scientists and nature lovers looked on in horror and then heartbreak as many of our ancient redwood forests were incinerated.

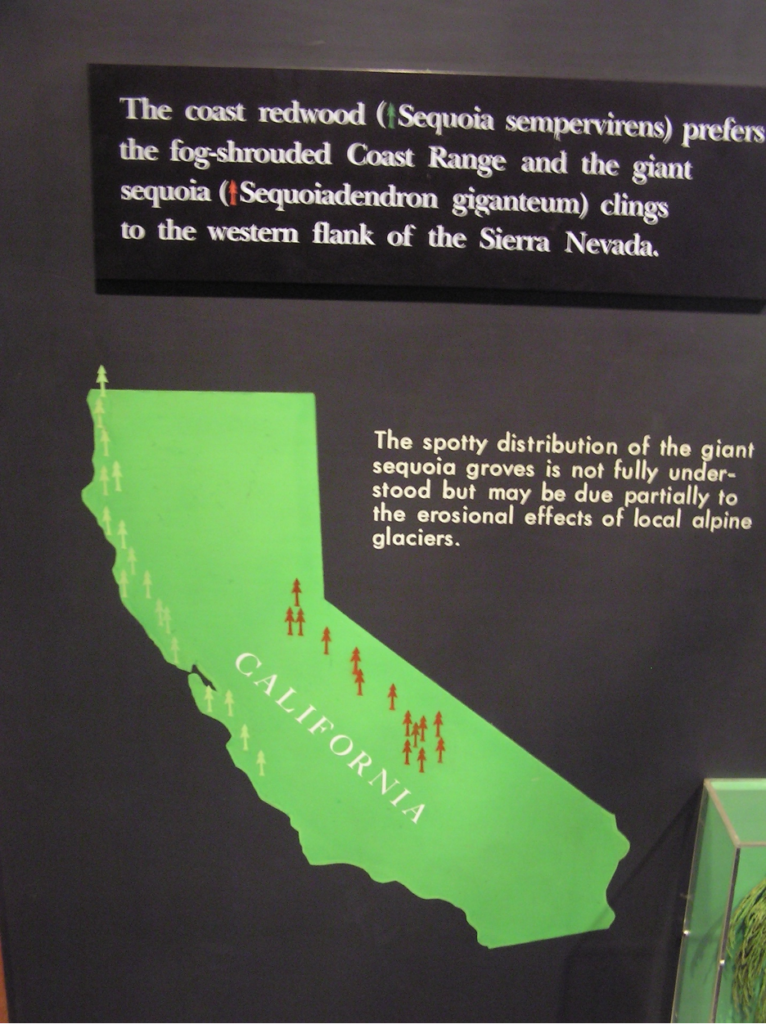

The largest, hottest, and most destructive wildfires in California history swept through from 2015-2021. But the long-term effects of these intense burns in our redwood forests have been quite different, depending on the contrasting species and plant communities: Giant Sequoias (Sequoiadendron giganteum) along the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) along the north coast fog belt.

As winter storms drift off the Pacific and encounter the Sierra Nevada, air is forced to rise up western slopes, where it cools and condenses, dropping abundant orographic precipitation. Heavy snows are common, which gradually melt into the deep sandy soils as spring advances toward summer. Giant sequoias rely on this meltwater into the summer drought. Occasional summer thunderstorms might also briefly interrupt the seasonal droughts, but they are not such reliable sources of water. However, those summer storms also produce lightning that ignites fires in Sierra Nevada forests, producing a fire season that peaks during the hotter summers and often lingers until the first early winter-season storms can douse them.

Following decades of fire suppression and accumulating fuels since the 1800s, and the introduction and invasion of highly combustible nonnative grasses and other species, a devastating megadrought plagued California. It started around 2000 and lasted for more than two decades. (These weather patterns and their impacts have been highlighted in multiple stories on this website and in my new book, The California Sky Watcher.) Though this historic dry period was punctuated by a few brief wet episodes and floods fueled by powerful atmospheric rivers, gradually warming temperatures and extreme summer heat waves quickly evaporated water out of our ecosystems and into the atmosphere with increasing vapor pressure deficits. Weather stations across the state repeatedly recorded their hottest days, months, and seasons, breaking all-time records. Bark beetles and other opportunists exploited the moment, further weakening native species and ecosystems already under stress.

From 2015-2021, at least six major fires raged through 85% of Sierra Nevada’s giant sequoia groves. The most destructive was the Castle Fire in August 2020, which killed 7,500-10,600 giant sequoias or about 10-15% of all Sequoiadendron giganteum on Earth. In September, 2021, the Complex Fire killed 1,300-2,400 giants and the Windy Fire destroyed another 900-1,300 of our cherished ancients that can grow up to 3,000 years old. All three named wildfires were ignited by lightning. By the end of 2021, nearly 20% of all giant sequoias had burned to death within only seven years. And now, it is feared that denuded ecosystems and other stresses could kill more fire-ravaged trees as we witness delayed mortality rates. I remember watching Christy Brigham (Chief of Resources Management and Science at Kings and Sequoia National Parks) on national network TV, as the media interviewed her in their stories about the devastating fires. Years earlier, Christy had worked with my students, helping to guide my field classes into her research. Fast forward and there she was again, the celebrity ranger and scientist under the Sequoias, attempting to educate a national audience about the importance of managing our forests and limiting climate change so that we might save what unique and precious resources remain.

We have learned how our giant sequoia forests, like other California plant communities, thrive with occasional wildfires. Older, tall sequoias have thick, fibrous, fire-resistant bark and they drop lower limbs as they grow so that fires can’t leap up from below into their towering crowns. Heat from the fires below encourages seed dispersal into recently-cleared soils. Over the millennia, these forest floors were regularly cleared by occasional ground fires that consumed accumulated fuels and took out smaller trees before they could act as chimneys to guide the flames higher. After more than a century of fire suppression, we realized our mistakes. But when the megadrought hit, it was already too late and it will take decades to reverse these trends that humans have set in motion. And so, the ancient giants burn and die.

Moving to the Coast

Coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) also benefit from heavy orographic precipitation (up to 100 inches/yr.) that falls when winter storms sweep off the Pacific and encounter coastal slopes. But snow is rare in these moist and cool, but milder climates. Instead, these forests remain damp through most of the summer drought season by catching coastal fog that drifts off the Pacific with the cool sea breeze and then drips down to the forest floor. Since these thick, shady forests appear relatively green and lush throughout the year, and they hold some the greatest biomass of any California terrestrial plant community, it is more difficult to imagine how fires could be such important players. But they are, especially after drought years capped by hot summers.

This is exactly what happened in August of 2020, when yet another summer heatwave sucked remaining precious moisture out of the redwood forests near the end of the megadrought. A series of thunderstorms with dry lightning drifted across California, igniting wildfires in already parched plant communities. The August lightning teamed up with the ongoing megadrought to make 2020 the worst wildfire year in state history. Nearly 10,000 fires burned over 4.4 million acres (about 4% of the entire state).

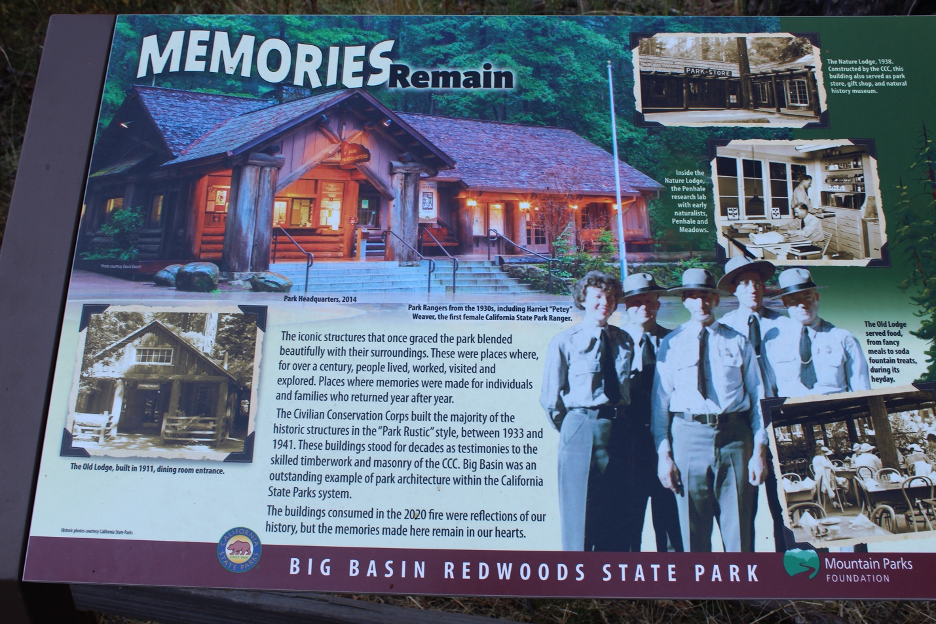

Multiple ignitions grew into three blazes that combined to form the CZU Lightning Complex Fire, which ripped through nearly all of Big Basin Redwoods State Park, including some of the most beloved coast redwood groves. As pictures filtered through the media, public shock turned to heartbreak. Intense, hot fires feeding off accumulated dry fuels sent flames high into the sky and into the canopy, torching magnificent coast redwoods that had stood for more than 1,000 years. Park headquarters, visitor centers, and other infrastructure turned to ashes. Everything in our cherished forest, where I had sought refuge decades earlier to admire and learn from the wonders of awesome nature, was burned to a crisp. Beloved Big Basin, home to the most southerly extent of our largest old-growth coast redwood groves, accessible to millions of city dwellers in the Bay Area, and treasured by millions of others in and beyond California, was gone. Or, was it?

Here is where the two fire stories diverge as we recognize even more glaring contrasts between the Golden State’s two redwood species and their plant communities. In the links that follow this story, you will see a Big Basin that appears to be burning to the ground. But new redwood growth appeared within weeks after the conflagration, such as basal burl sprouts and sprouts from tree trunks. Decades of carbon storage emerged to the surface as fresh green shoots. And by the time I returned to my cherished sanctuary, recovery and natural regeneration was evident everywhere, only four years after the inferno.

Though the firestorm killed understory species and most Douglas firs, nearly every scorched redwood was sprouting, evolving from snag tress that began to resemble bottlebrush trees. Not only were sprouts emerging from the base of the trees, but charred limbs were being covered with fresh, fuzzy green growth. This is not to understate the damage that had been done. It will take generations for these forests to recover. More xeric chaparral (such as ceanothus) and ecotone species had invaded open spaces that had previously been cool, moist, shaded enclosures sheltered by a redwood canopy. Invasive weeds included crowding opportunists such as French broom and yellow star thistle. Much of the former forest floor was now exposed to intense direct sunlight, encouraging sun-loving invaders that can withstand large daily and annual temperature swings. Exposed creeks and streams ran much warmer in the summer and carried high sediment yields during the winter rainy season. Just before I arrived in 2024, local air temperatures soared over 100°F during an early July heatwave. But the seared coast redwoods somehow survived it all, and a rich diversity of flora and fauna was returning and evolving in a fantastical story of rebirth. Birds and other wildlife, such as raccoon, fox, deer, coyote, and mountain lion were finding homes within the recovering diversity of habitats.

The two contrasting redwood fire regimes in this story leave us with plenty of science lessons about the natural systems and cycles that nurture such forests. As you might expect, these burnt landscapes are attracting researchers from around the world. They include scholars from the Stephens Fire Science Laboratory, the California Fire Science Consortium, and the UC Center for Fire Research and Outreach. The following are just a few summarizing thoughts.

Our most diverse forests represent more resilient plant communities capable of adapting to gradual and sudden extreme changes. Occasional cool fires encourage a diversity of habitats and plant species, which support more diverse animal species, ranging from bees and other insects to much larger predator and prey. By contrast, aggressive fire suppression leads to stagnation and homogeneity, which could lead to the demise of species and entire ecosystems. Likewise, if hot fires reoccur too frequently, introduced grasses and other invasive fire-loving species could encourage even more frequent fires that alter ecosystems. If you think this suggests a delicate and complicated balance, you nailed it. For centuries, most California ecosystems adjusted to relatively cool fires with spotty hot flareups; redwood forests had adjusted to high fire complexities with a large variety of burns that may have returned every 6-35 years or so. Suppressing such fires disrupts natural succession. However, super-hot, frequent fires everywhere can also disrupt natural cycles, leading to decreasing species diversity and ecosystems less resilient to changes that can destroy them. During the last two centuries, humans have interfered with these natural cycles, which has encouraged high fire intensities and severities capable of searing nearly everything in the forest.

In the bigger picture, there are many more examples of how humans have directly impacted California’s natural fire cycles. The most dramatic changes can usually be found in what has gained a most descriptive and popular name: the wildland-urban interface (WUI). We can’t allow wildfires to destroy billions of dollars in property and kill people as they sweep into our communities, so we try to stop them at our fabricated boundaries. But what is considered defensible space is negotiable in a fire regime where burning embers can be blown over a mile from the active front by high winds. These dilemmas become particularly evident as we encroach further into nature and extend our human footprints. How can we ever restore natural fire cycles when we inevitably find ourselves living adjacent to the very natural landscapes we wish to preserve?

Human impacts on particular keystone species have also changed our fire cycles. As just one example, wildlife officials are working to reintroduce the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis) into select waterways across the state. This keystone species is now considered an ecosystem engineer that expands diverse habitats that then increase and improve nature-based ecosystem services. Beaver dams and ponds widen water courses and raise water tables to irrigate larger, lusher, more diverse and productive riparian habitats and gallery forests. Wildfire behaviors change drastically when they approach such wider, well-watered green barriers. Imagine the countless other ways that assisted natural regeneration can increase ecosystem functionality after a forest fire and help reboot our wildlands back toward their natural fire cycles.

I’ve been walking into and gazing up to these magnificent wonders-of-our-world forests to admire and study giant sequoias and coast redwoods for five decades, assuming they would outlive me. I and some of my field students sensed the changes over time. During my next visit, I wonder if these venerable towering elders will be poking fun at me for thinking five decades is a long time. Only now, I must also wonder which of us might be first to decompose into the dust of future generations.

Still looking for more? Check out the following rather exhaustive list of articles and videos summarizing recent research in California’s redwood forests. There is plenty to unpack here, but you are rewarded by hearing and learning from the experts. Following the links, join me again as I take you on more lengthy self-guided photo tours through these forests.

The first three links are to stories on our website (that now date back several years) highlighting California’s wildfires and/or redwood forests. You can also surf through our website to find multiple stories about weather patterns and climate change. Next is the list of articles and videos from the forests. The final links take you to the most recent researchers using geospatial technologies to help us understand how species are adapting to these changes.

The Wildfires of 2020:

Forest management and research and perspectives from of one of my former students working in the redwoods:

Encountering coast redwoods with colleagues on a field trip in northwestern California:

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Research Projects

Fire Reoccurrence in the Sequoias

Good Article about Sequoias and Fire, with Video, from Outdoor Magazine

Here is an old NPS article describing the redwoods.

NPS on the Sequoia Fires 2015-2021

NPS on Giant Sequoias and Fire

Castle Fire Research Video from Scientific American

The following three articles focus on Big Basin:

Fire recovery survey, April, 2022, written by Biologist Steve Singer

Save the Redwoods League Article Summarizing Recovery at Big Basin

More on California’s Coastal Redwoods:

Nature Plants Article on Regrowth in Coastal Redwoods

Indigenous tribes rekindle control burning in northwest California forests.

Northwestern California Karuk and Yurok tribes revitalize cultural burning.

If you can navigate through the commercials, “It’s History” recalls what happened to most of our coast redwoods.

Do you want to dig deeper into recent related research projects? It turns out that California has become a laboratory for using cutting-edge geospatial technologies to map our evolving plant communities and their thousands of species. Scientists and citizens are using these new technologies to track species as they adapt to climate change, fire, and a host of human impacts. Check out these links, but give yourself some time if it’s all new to you:

The summary sent from Bill Bowen

You could start here if iNaturalist is new to you.

Evolutionary adaptation of species to climate change at the MOILAB

For you more curious and adventurous folks, the following photo essays take you through several of our redwood forests. These colorful tours represent a lifetime (decades) of adventures, field trips, and research projects in California’s redwoods. I used some of the signage in each park to take the place of captions and to give you the sense that you are walking with me. You may notice that no photos were manipulated. Here’s your chance to lose yourself and learn from the forest. Click on each page to walk through a different region.