Hurricane Dorian, after battering the Bahamas on Tuesday (09/03/19), has today pivoted to threaten the Carolinas. Though downgraded from a Category 5 to a Category 2 storm, Dorian still has sustained winds of 105 mph. One person in the U.S. has now been confirmed killed by the dangerous and unpredictable cyclone. Many more deaths have been tied to the storm in the Bahamas. That death toll may still rise. More than a million people in the southeastern United States currently face evacuation orders. Often in such trying times Californians may wonder, could a hurricane happen here?

Photo credit NOAA.

California certainly has its share of natural disasters. Earthquakes, fires and floods are the most familiar and damaging calamities that impact the state with frequency. But what of hurricanes?

Fortunately for The Golden State, these monstrous and dangerous tropical storms have not historically been a serious threat. Occasionally, during a special convergence of weather circumstances, the remnants of these powerful storms will affect the southern portion of the state and deliver high winds and heavy rains. Rarer still, a disturbance of tropical storm intensity will batter the lower latitudes of the state. But so far, no actual hurricane has made landfall in California in recorded history.

However, there were a few that came very close. In 1858, a storm with hurricane-force winds passed by San Diego before weakening just offshore. And in 1939, a tropical storm actually did make made landfall near Long Beach and caused significant damage. Additionally, hurricanes Joanne (1972), Kathleen (1976) and Nora (1997), all brought tropical-force winds to the southeastern corner of the state before tracking off into Arizona.

Photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library.

There are two important reasons why California is rarely affected by tropical cyclones: water and winds.

Water

Water temperatures are the single most important factor in hurricane development. In order for tropical cyclones to form and grow they require an abundance of heat stored in the ocean waters to a depth of ~150′. Ocean surface temperatures need to be at least 80°F for a tropical depression to even start forming. This happens every year in the tropical Atlantic. In the southernmost waters off the California coast, however, it is rare for the surface ocean temps to reach 75°F. Farther from shore ocean temperatures, even at the end of summer, are usually only in the mid 60s.

These relatively cool temperatures are due to the action of the cold California Current and eddies that form offshore, the latter creating upwellings that bring cold water from deep below the surface. The cold waters not only prevent hurricanes from forming, they also act as a damper or barrier to any tropical storms that might wander in from the south. The colder the water, the quicker any tropical disturbance will dissipate.

Winds

Most eastern Pacific hurricanes start off as tropical depressions in the coastal waters off Mexico, south of the Tropic of Cancer. From there, prevailing wind patterns will push them in a generally northwest direction, where they will begin to weaken once they drift over cooler waters. The vast majority of these storms will dissipate far from shore in the central Pacific having never made landfall in California or elsewhere.

But during strong El Niño years, water temperatures off the coast of the eastern Pacific, including California, can be much higher than normal. And in recent years, high pressure “domes” have been observed stagnating over the Great Basin and Mountain West. This phenomena allows coastal winds to blow from the south and east, instead of their normal origination in the northwest, warming the waters and potentially shepherding storms in as well. These factors can also slow the dissipation of tropical disturbances as they wander north, and occasionally, allow some of these storms to stall out near the coast of southern California.

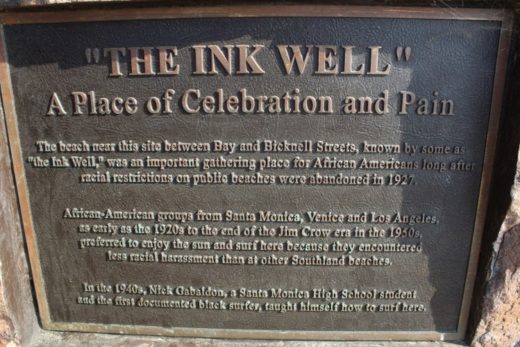

That’s apparently what happened on October 2, 1858. Details are sketchy as few people, and even fewer meteorologists, were on hand to record the events. But by piecing together what reports and observations were available, researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, were able to model the atmospheric conditions on the southern California coast at that time. They concluded that the event was the “the only tropical cyclone known to produce estimated hurricane force winds” on the California coast.

By 1939 there were a lot more people on hand in The Southland to observe and record the tropical storm that actually made landfall and caused an estimated $2 million in property damage. The coastal areas were most affected, with ships and structures immediately on shore suffering the greatest damage. But heavy rains also caused local flooding and erosion throughout the L.A. Basin.

Past weather and climate data are still the best indicator for current and future conditons. But we now live in a world where the equations are changing more rapidly than ever. An ominous indicator of such change was recorded last summer off the coast of La Jolla. Scientists from Scripps Institution for Oceanography recorded the highest ever sea surface temperature (78.6°F) in California waters. These warm waters were 5-10°F above normal and extended as far north as Point Conception. Granted, this was but one example. But it is one example in a growing list of such examples that is evidence of a global trend.

Some argue that even with modern technologies, precise forecasts about exactly when, where and how strong a hurricane’s devastation will be is difficult. This is true. So many dynamic factors are involved in a tropical cyclone that it would be impossible to precisely model them all. But when it comes to forecasting the weather, science can accurately account for the probabilities if not the actualities. In that regard, climatologists are in agreement that global warming has not only contributed to the frequency and intensity of hurricanes, it will likely bring these devastating storms to new regions of the globe previously thought to be immune to their wrath.

This includes California.

Photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library

References et al:

Check out NOAA’s Historical Hurricane Tracker.

Christopher Landsea. “Subject: A16) Why do tropical cyclones require 80 °F (26.5 °C) ocean temperatures to form ?”. Tropical Cyclone FAQ. National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2091-09-04.

Christopher Landsea & Michael Chenoweth (November 2004). “The San Diego Hurricane of October 2, 1858” (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. American Meteorological Society. p. 1689. Retrieved 2019-09-03.