Researching Heat Risks and Heat Wave Trends with the National Weather Service

On October 18, 2024, I was fortunate to attend the fall National Weather Service workshop for educators. It was organized and led by NWS meteorologist Todd Hall, hosted by Jodi Titus at Irvine Valley College, and guest presenters included Steve LaDochy. The general theme was “Heatwaves”.

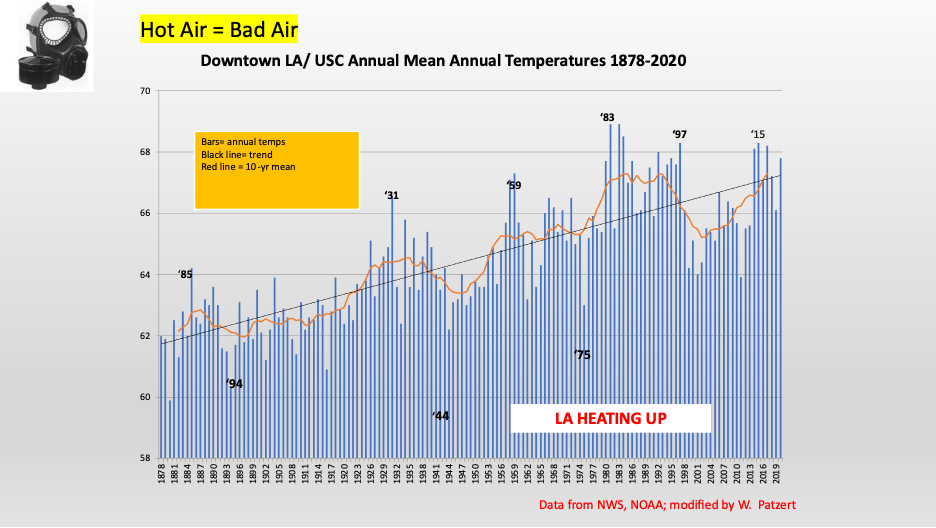

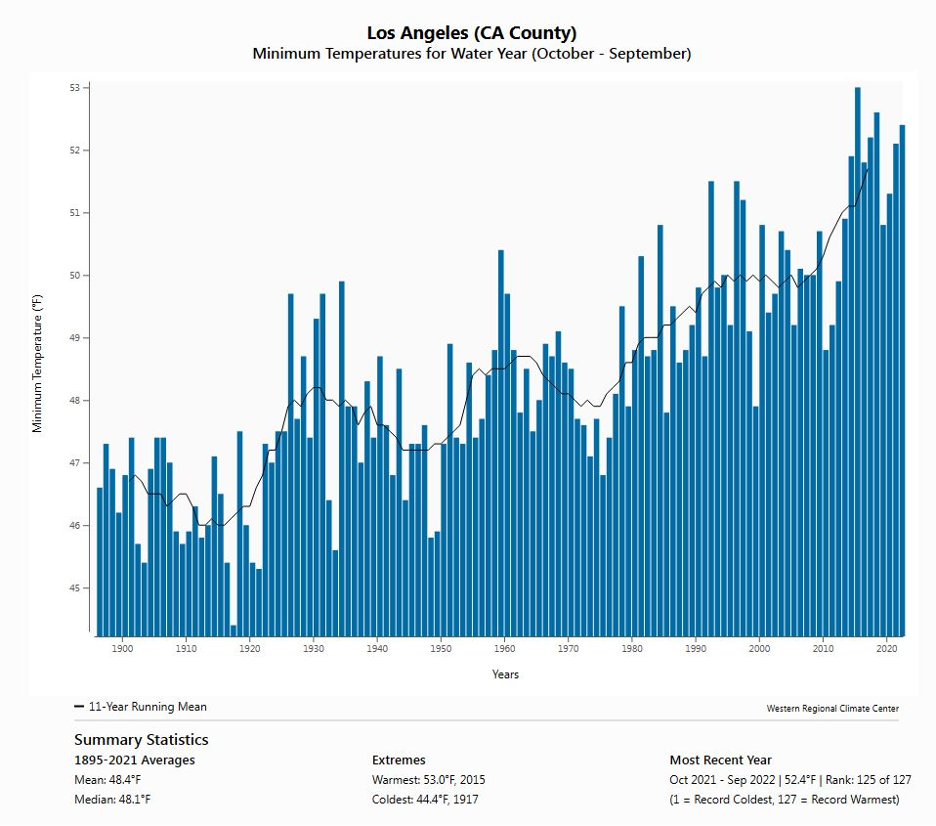

Steve LaDochy walked us through the increasing heatwave trends in Southern California. (He, climatologist Bill Patzert, and other meteorologists have emphasized the importance of keeping weather stations at the exact same locations if we are to make reliable measurements that can be compared over many decades.) For instance, downtown LA experienced approximately 5° F of warming from 1878-2020. But general long-term warming trends common throughout California are not so steady over shorter periods. They can fluctuate with ocean current and temperature cycles in the Pacific that include PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation) and shorter ENSO (El Niño/La Niña) events. (The ocean has 1000X the heat capacity of our atmosphere and has absorbed more than 80% of the additional global energy so far.)

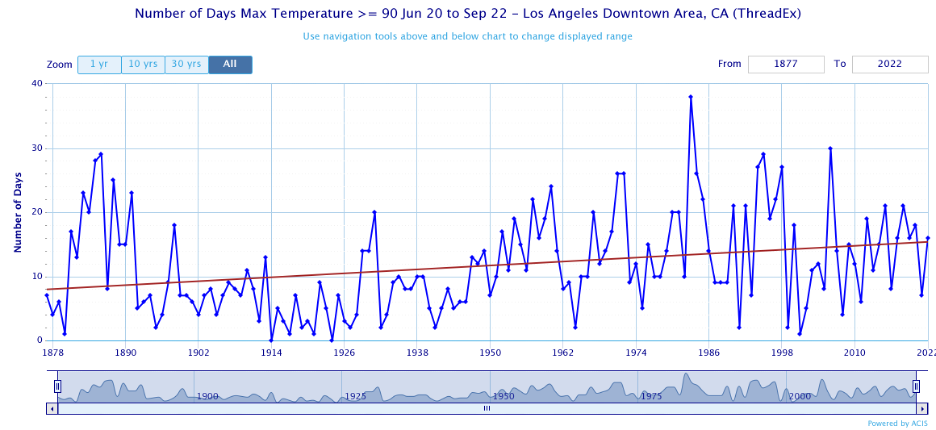

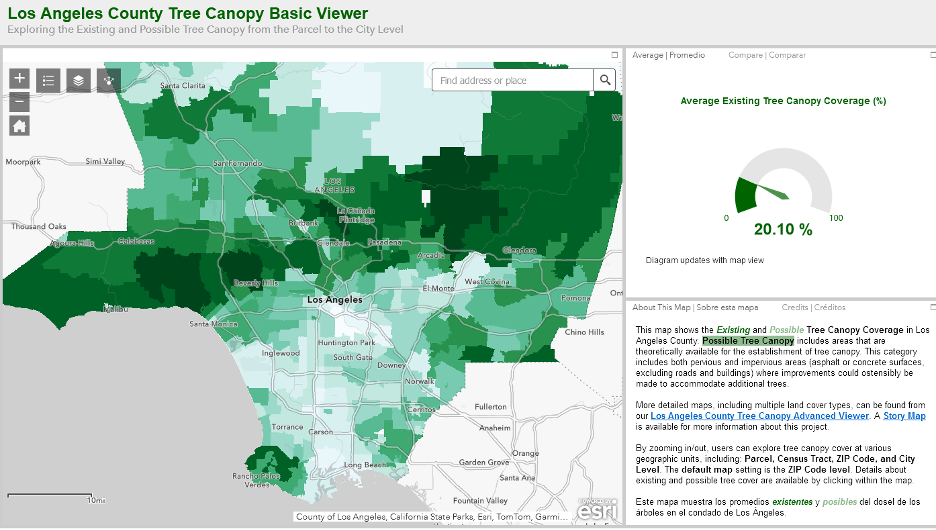

Some of the details gleaned from this workshop reveal a clearer picture of climate trends and their impacts. In downtown LA over more 140 years, the number of days when temperatures soared above 90° F has been increasing while other stations across the state are experiencing similar trends. For instance, the length of heatwaves (100° F or above) in Woodland Hills (in the hot western end of the San Fernando Valley) has also increased dramatically. The Central Valley (where the largest number of heat-related deaths and illnesses are often recorded) is also experiencing increasing frequencies of more extreme and lengthy heat waves. This led to a discussion of how we can cool our urban heatwaves by planting trees and other vegetation, and with cool (light versus dark) and green roofs, and more permeable surfaces. Check out the AMS Conceptual Climate Energy Model .

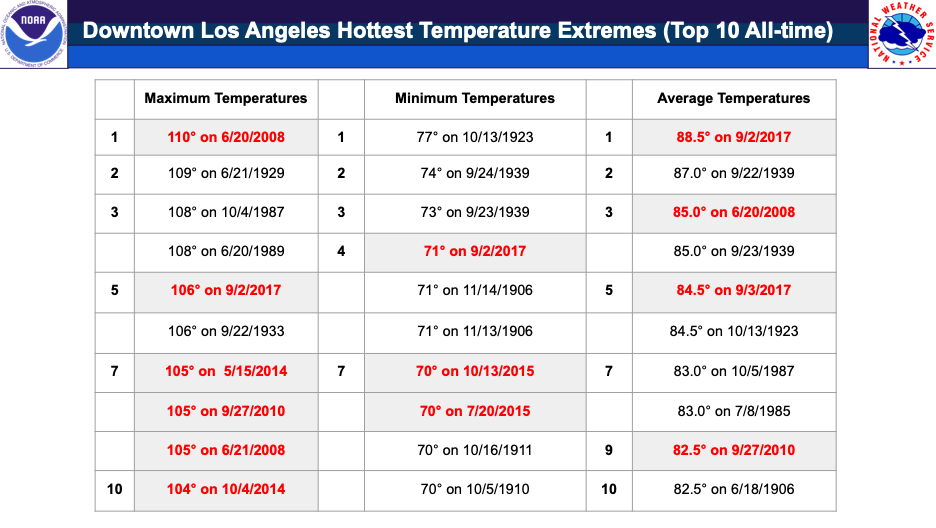

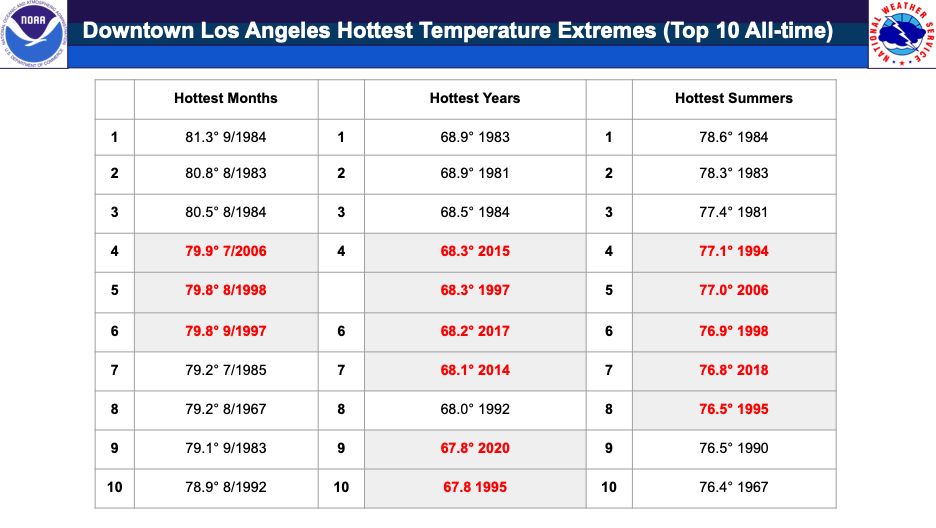

After a break, NWS meteorologist Todd Hall took center stage. Todd shared some of his recent research showing temperature trends for selected weather stations that had accumulated around 110 or more years of data. His climate change in relation to Southern California heatwaves discussion focused on the hottest temperature extremes during true summers (6/21-9/20). His research confirms the established trends summarized in our workshop and in other stories on this website. Though the entire state has been warming at roughly the same rate as the planet, there are noticeable differences in each region. Inland areas are warming faster than coastal locations, likely because they are not benefitting from the modifying influences of less changeable ocean water temperatures and sea breezes. Urban areas are heating faster than rural regions due to urban heat island effects. Combine the variables and we see why most inland cities are heating up faster and coastal rural locations are warming slower.

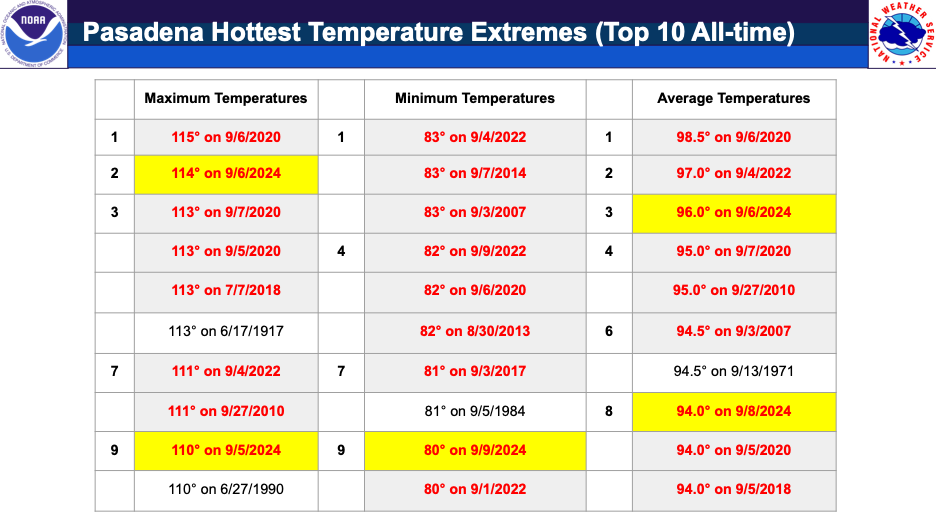

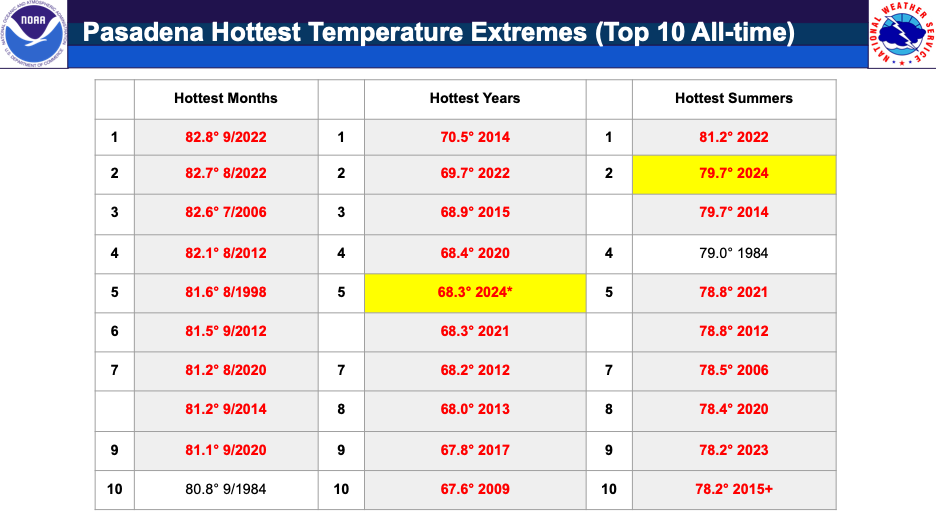

So, as we might expect, the data shows most coastal locations such as Santa Maria, Lompoc, and Santa Barbara warming slower than inland stations. I picked out two example cities to display from Todd Hall’s research. Both LA and Pasadena have been impacted by global warming, plus the effects of expanding urban heat islands over many decades. Note how the hottest temperature extreme records are concentrated during recent decades and even years. The difference is that Pasadena is farther from the coast, so that sea breezes arrive later in the day and are more modified when they arrive. We can sense how extreme heat risks are increasing for inland valley populations (such as from the San Fernando and San Gabriel Valleys, east into the Inland Empire.) Similar trends are being measured as we move east from the modifying influence of San Francisco Bay and deeper into the Central Valley.

We can now understand the need for such research and this website story. Todd Hall summarized how we are using better tools to redefine increasing “heat risk”. These efforts are crucial to preventing illness and saving human lives since heatwaves kill far more people in the US and California than any other weather events. Though causes are often misdiagnosed as other illnesses, we can already recognize more than 100 heat-related deaths in California each year. Nationally, they account for 2X the annual flood-related deaths and far more than tornadoes, lightning, hurricanes, and freezing cold. As expected, heat fatality numbers run higher in more populated regions, but the percentages of deaths are higher in rural areas, where people tend to be more exposed to the elements.

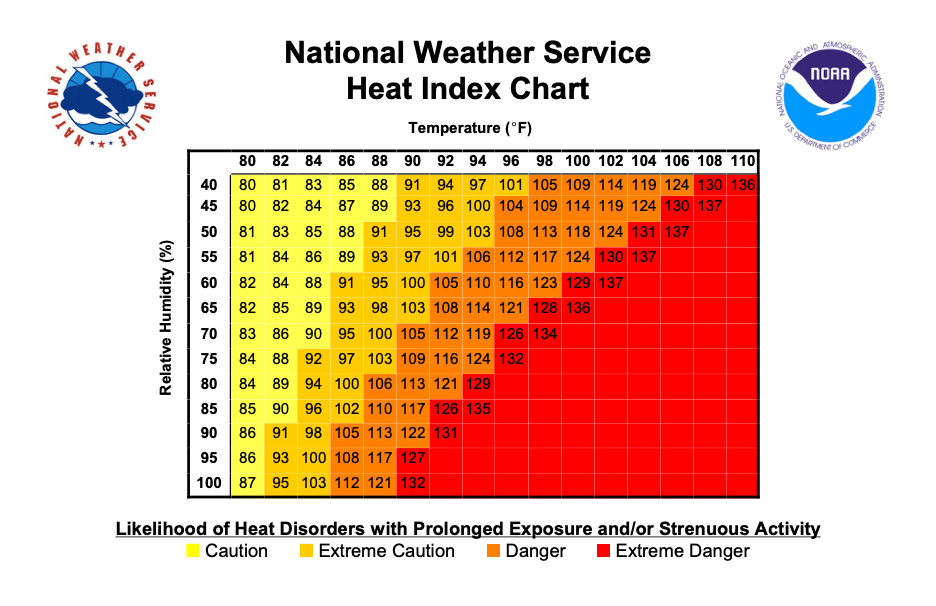

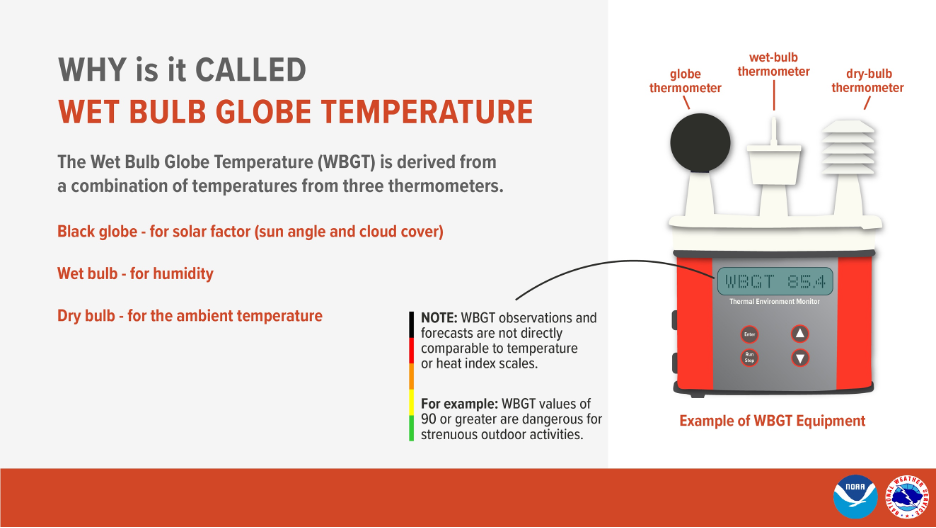

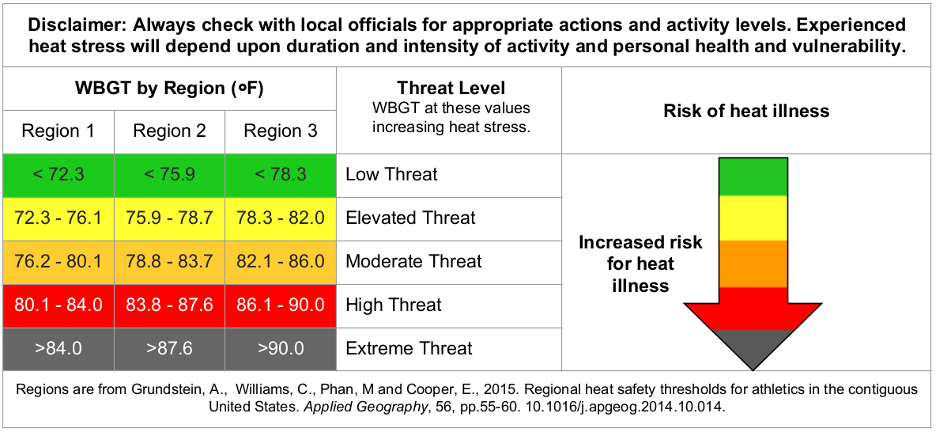

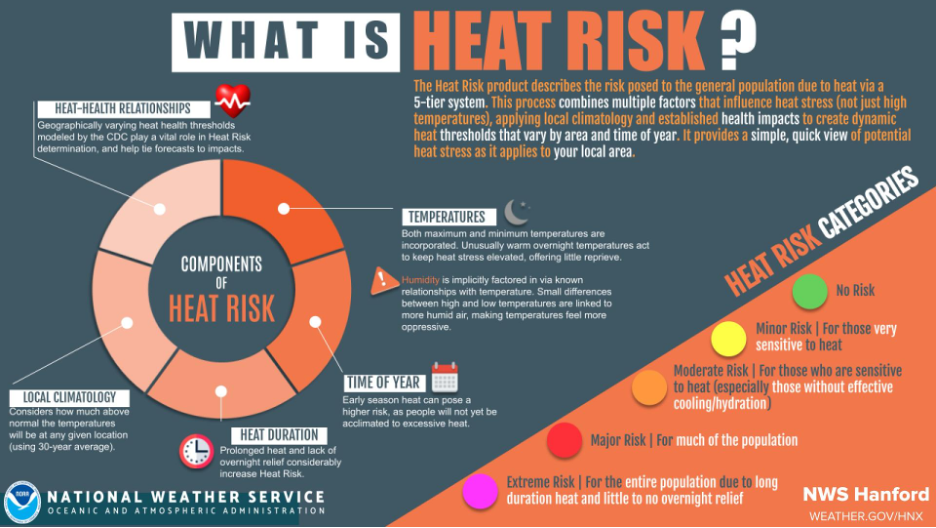

Here is a summary of three evolving National Weather Service forecast tools used to assess heat risk to humans. The traditional “heat Index” is most popular with the general public. The simple chart (and formula) uses temperature and humidity to assess how we might feel. As emphasized in previous stories on this website and in my California Sky Watcher book, we should feel cooler on hot dry days due to the rapid evaporative cooling of perspiration from our skin. High humidity hot days are less comfortable. But the more sophisticated wet bulb globe temperature is a more accurate measurement of our heat discomfort, such as when we are or are not exposed to direct sunlight. The NWS is now working with the CDC to more accurately include and measure other variables that determine “Heat Risk” to humans. These involve measuring wind, duration of the heat event (including overnight low temperatures), local climatology (such as the average for the date), and acclimation. The following images summarize these three methods.

Looking for more? Surf through this rather exhaustive list of links that will guide you into the world of heat:

AMS Conceptual Climate energy Model

The costs of Extreme Heat in California from Cal Matters

Health Impacts of Climate Change

Heat-related Deaths and Illnesses in California

With Tables

California Heat Assessment tool

Article on Heatwaves in Southern California

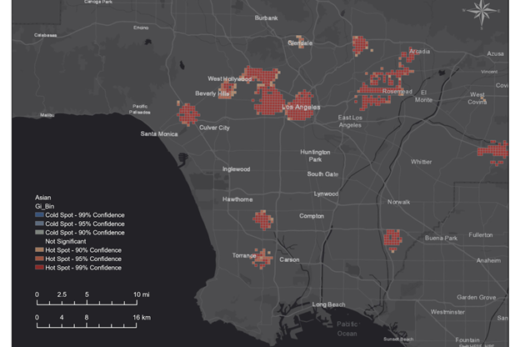

UCLA Heat Maps Using GIS to Illustrate Climate Resilience

Tracking California Heat-Related Illness

Explaining Heat Risk from the NWS

Compare today’s California high temperatures with the nation

NWS Weather Calculator including temperature, moisture, pressure, and wind, conversions by Tim Brice and Todd Hall

Mortality in extreme heat events: an analysis of Los Angeles County Medical Examiner data

Warmer ocean temperatures can result in noticeably warmer nights and an increase in average temperatures. Check out these Marine Heat Wave links:

THE END

Excellent!! Good overview of heat waves and heat risks. Also enjoyed reading the synopsis of fall weather.