Day Two (Sunday, 4-13-2025): Geology, Creation, and More than 100 million Years of History

Our full day started as most would during this naturalist week in and around Yosemite: Up after 6, share breakfast at 7, pack our lunches, and into the bus (piloted by mild-mannered and unfailing Jim) by 7:30am for a long day of discovery. We travel north on Hwy 41 into Yosemite National Park, past Wawona, along the winding mountain road and some extensive burn scars, and through the Wawona Tunnel (the longest highway tunnel in California). Emerging on the other side, the Tunnel View stop offers iconic panoramas into Yosemite Valley, made famous by Ansel Adams and other early photographers, and now a must photo for selfie addicts. When the weather is cooperating, this first spectacular view has captivated millions of people, instantaneously connecting them to the awesome natural forces that shape such transcendental landscapes. Our National Park Service ranger guide points out what remains of the old stagecoach line that was dynamited into the steep, unstable talus slopes on the other side of the valley. Here is also a good place to recognize how California landscapes are constantly being constructed by internal tectonic mountain-building processes; once rock formations are lifted up, the external denudational processes of weathering and erosion prepare material to be transported back down toward sea level under the force of gravity. The winner in this ongoing contest to build or destroy will determine whether landscapes will be lifted higher or denuded lower over time; current research suggests that much of California will grow even bumpier and higher over the coming millennia.

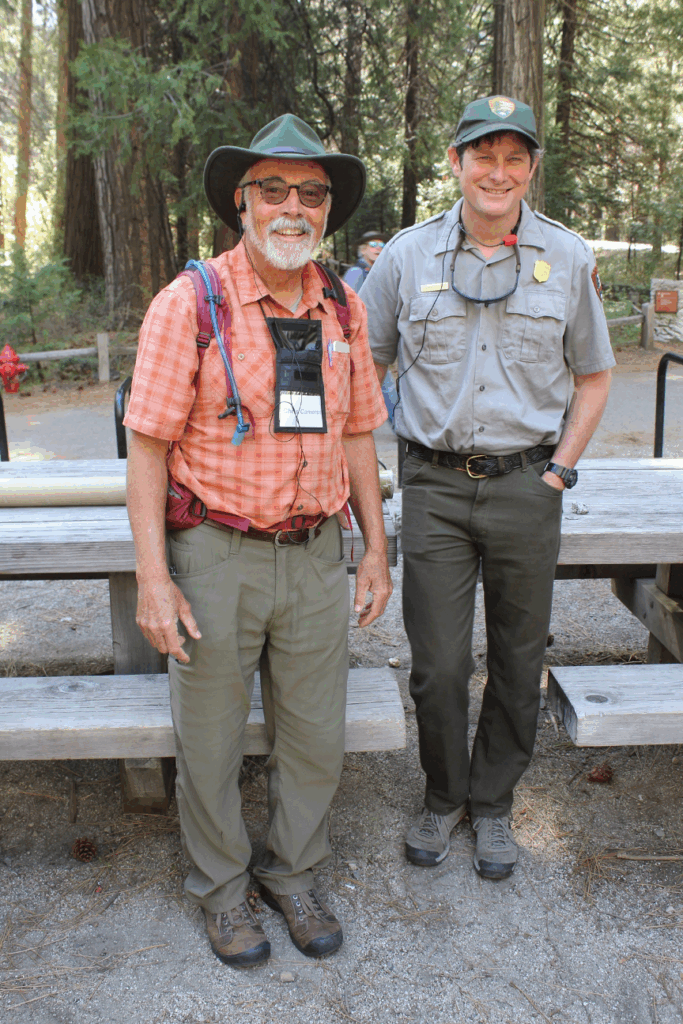

We then meet today’s ranger guide in the valley. Greg Stock was Yosemite’s first geologist. He has overseen a mountain of research in Yosemite, discoveries that have shed light on geologic processes that are shaping landscapes here and all over the world. He starts with a summary of plate tectonics (accepted and amended in the scientific community ever since the 1960s) and related concepts that we have covered in previous stories on this website, such as Geologic History in Sierra Nevada Gold Country. During the Mesozoic Era, when subduction was the dominant plate boundary below what is now California, enormous magma chambers formed miles deep. These giant melts, or plutons, would gradually cool and crystallize into what we recognize as the massive Sierra Nevada Batholith, mostly composed of high-silica granitic rocks. The slow cooling (taking thousands to millions of years) allowed the quartz, feldspars, mica, and some darker crystals to grow large enough to create the larger and sometimes shiny speckles we see in today’s granites. Such batholiths make up the cores of most California mountain ranges and they are dated by the times they crystallized. On average, we use about 100 million years to summarize these ages, but there is much variation between each pluton even within this Sierra Nevada/Central Valley microplate.

Though they were once buried thousands of feet deep (3-5 miles), more recent mountain building has thrust these rocks (and those once above them) upward, allowing external processes of weathering and erosion to take over. (Most of today’s Sierra Nevada mountain building is the result of vertical faults lifting up the steeper eastern slopes of the Range of Light.) The higher elevation overlying rocks have been stripped off and carried away, exposing these granitic rocks that tower above Yosemite Valley. Many of the stand-out domes we see today are formed by exfoliation; when overlying rocks are weathered away, pressure is released, allowing these rocks to expand. As the domes form, the brittle rocks break into concentric layers that look like onion-like skins separated by cracks and fractures. These processes accelerate physical weathering, leaving slabs of granitic rocks to slide and fall off steep slopes. All of the physical and chemical weathering processes combine to create one of the most active rockfall landscapes in the world, making Yosemite the epicenter of rockfall research. And that’s where our Geologist and NPS Ranger, Greg Stock, takes center stage.

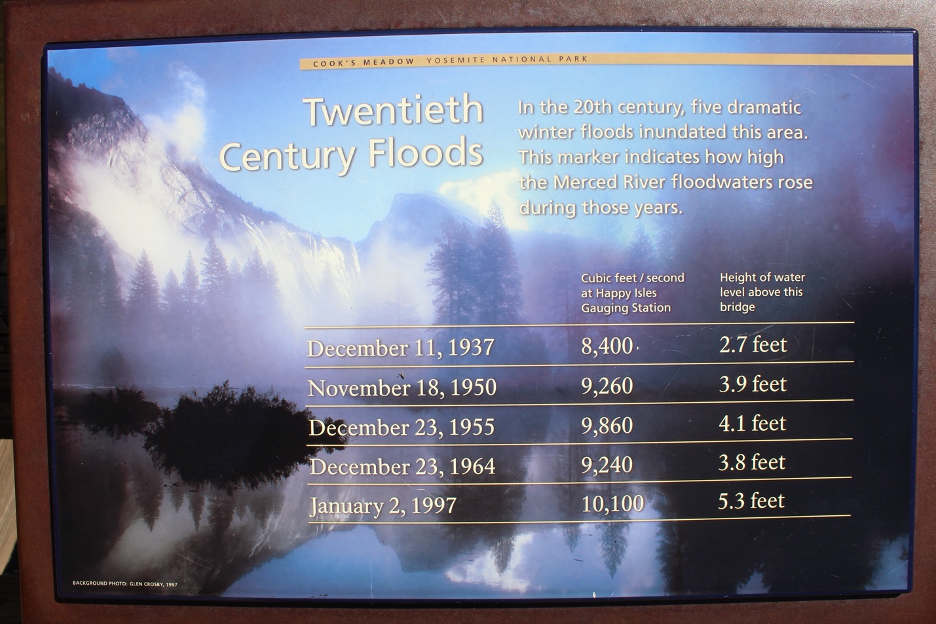

On average, rockfalls are reported about every five days around Yosemite. They range from minor to catastrophic, the largest over 6,000 cubic meters (a cubic meter is about the size of a refrigerator), and they have been responsible for 18 fatalities and more than 100 injuries during the park’s history. Greg Stock and other experts were brought in following the catastrophic 2008 rockfall that buried a portion of Curry Village. Following the assessments, parts of the village were moved away from rockfall hazard zones, which saved what would have been numerous casualties when subsequent rockfalls tumbled down just a few years later. But keeping people and infrastructure out of such hazard zones isn’t easy in such a narrow valley. Moving facilities way from the higher terrain at the base of cliffs can place them on lower portions of the floodplain, which experience occasional catastrophic flooding. A balance must be achieved to keep Yosemite Valley accessible and it is likely that careful management has reduced damage from such natural hazards in Yosemite Valley by 95%. A big thanks goes to Greg Stock.

Meanwhile, recent research has utilized technologies (such as time-lapse filming, deformation and temperature gauges, laser scanners, and crackmeters) to show how temperature stresses are opening and closing cracks and fractures in cliffside rocks (nearly ½ inch each day) as the rocks expand and contract during hot days and cold nights. Other weathering processes become obvious in the form of those dark and multicolored vertical streaks on cliff faces. These stripes form where runoff tends to linger or trickle down the rocks, accelerating the oxidation of iron, manganese, and other heavy metals and creating microhabitats that encourage organic growth such as lichen (recent studies suggests that there are up to 500 species of lichens in the park).

We can’t wrap up our geology discussion without acknowledging how Yosemite Valley and its high country have been carved into such spectacular landscapes by glaciers. Most of this story was told in our earlier website story comparing Norway to California, so we’ll just summarize it here. Yosemite’s deep canyons were once (about 3 million years ago) carved into V shapes by water cutting through freshly exposed rocks as it cascaded in ancient streams and rivers down and out of such a youthful mountain range. A series of glacial episodes followed when temperatures dropped by about 4-5° C (7-9° F), allowing glacial ice to accumulate in the high country. The maximum glaciation occurred about 1 million years ago, when glaciers thousands of feet thick were pulled downhill by gravity, streaming into surrounding valleys.

The Merced and Tanaya Glaciers merged into Yosemite Valley to create a 2,000-foot thick alpine (mountain/valley) glacier that once scraped as far downhill as El Portal before melting in the warmer climes. The most recent glacial episode (known as Tioga, referencing the source of much of the ice from near today’s Tuolumne Meadows) had peaked by around 18,000 years ago and had retreated by about 11,000 years ago. These glacial episodes carved countless impressive glacial landforms into Yosemite high country, where year-around ice once covered most surfaces above about 8,900’. Bowl-shaped amphitheaters called cirques, saw-toothed ridges, scratches, grooves, striations, and glacial polish are erosional remnants still on display in high country bedrock. As glaciers were pulled downhill following paths of least resistance, they scoured the V-shaped canyons into deeper and steeper U-shaped troughs, similar to the trail you leave when you push your foot through loose sand. Moving downhill, they finally deposited mounds of unconsolidated debris that built sinuous glacial moraines. Lateral moraines were deposited on their sides and terminal moraines mark the valley glaciers’ farthest reach downhill. Stand out erratic rocks and boulders were left stranded as the glaciers retreated.

Sierra Nevada glaciers shrunk dramatically and may have even disappeared during warmer interglacial periods. For instance, it was originally believed that all Sierra Nevada glaciers had disappeared after the last glacial episode, then small glaciers reappeared, but that theory is being challenged by recent research. Isotopes in some high-country bedrocks show no evidence of any cosmic ray exposure since the Tioga Glacial Episode, suggesting that these glaciers never completely melted, but continually covered the rocks. Another thanks to Greg Stock for that update. Regardless, we can now better understand how glaciers played such important roles by carving into those steep cliffs and leaving hanging valleys with their waterfalls that help define Yosemite: https://www.usgs.gov/maps/extent-last-glacial-maximum-tioga-glaciation-yosemite-national-park-and-vicinity-california

Today’s streams and rivers continue to simultaneously fill Yosemite Valley with sediment weathered and eroded from higher elevations, while other currents also cut through it. Depending on the year, peak flows and awesome waterfall spectacles are usually on display around May when high-country snowpacks are melting fast. https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/geology.htm

During the afternoon, we stopped at the Discovery Center in Yosemite Valley. I reviewed the displays recalling Native American cultures that have populated this valley for thousands of years. Here is my attempt to summarize traditional Native American perspectives on natural history, as told by the people who shared their oral traditions at the Discovery Center:

The people of Ahwahnee (gaping mouth, or land of the gaping mouth) call themselves Ahwahneechee. Their creation story begins when Coyote Man and Frog Man traveled on a raft. Frog Man dove down to bring up some earth. Coyote man used this to make the land. Cougar Man, Grizzly-bear Woman, and others followed. Coyote Man then made people by turning two sticks into man and woman. Coyote Man then told Lizard Man and others to turn into plants and animals. The Creator led them all into Yosemite Valley, where they prospered with natural resources such as spring redbud, summer sedge, bracken fern, and winter mushrooms. Other resources have included obsidian, which Native Americans traded from the east side of the Sierra Nevada all around California. Flaking (a process called knapping) shaped the volcanic glass into valuable tools that included arrowheads.

The numerous colorful displays at the Discovery Center include a summary of the vegetation zones in Yosemite and throughout the Sierra Nevada, starting at the base of the mountains and traveling to the highest peaks. Yesterday’s climb along Hwy 41 from the Central Valley to Oakhurst wound from the lowest, hottest valley grasslands and prairies into the foothill-woodland zone. Today’s ventures past Wawona and Mariposa Grove’s big sequoias took us through the lower montane, briefly passing the upper montane zone. Since higher elevations are still covered with winter’s snowpack, we can only look up toward the subalpine forests and get brief glimpses of the highest alpine zone far and high in the distance: https://home.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/plants.htm

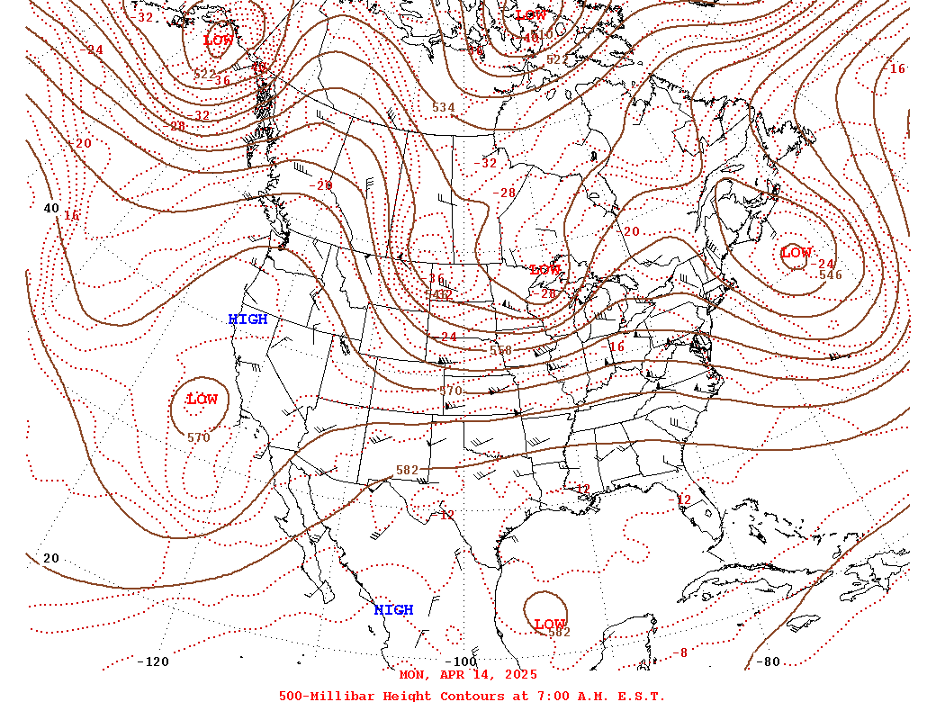

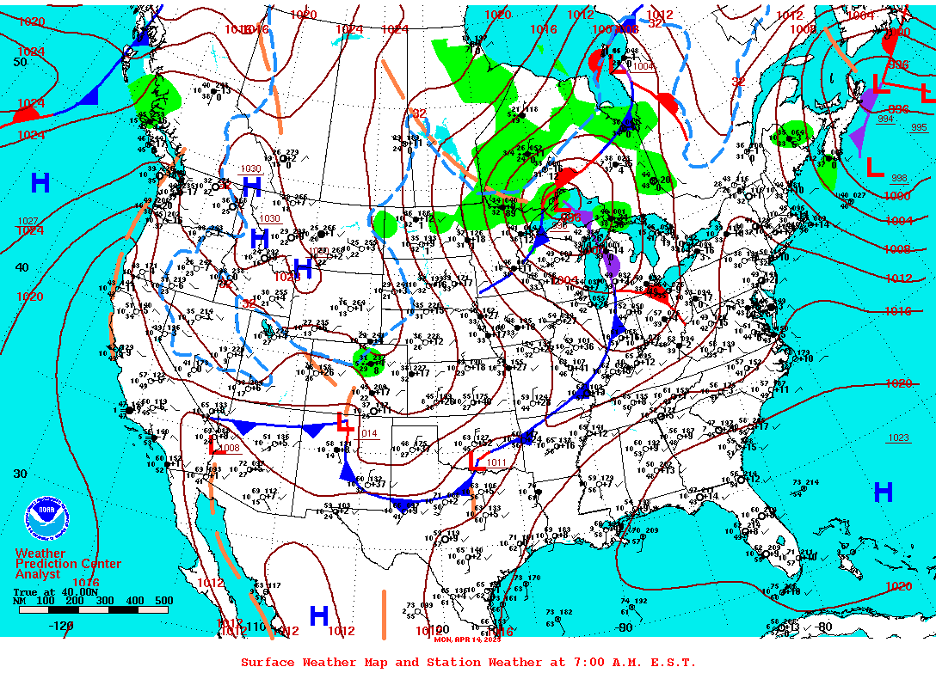

Weak high pressure continues to dominate our weather, producing mostly clear skies and daytime high temperatures in the 70s F in the valley and 60s just above. A few tiny, raggedy afternoon fair-weather fractocumulus clouds (Cumulus fractus) developed in the afternoon thermals, mostly over higher terrain, only to dissipate in the stable air near sunset. Clouds will increase during the next few days as the high pressure gradually yields to a weak upper-level cutoff low that will meander inland from the coast.

Click (below) to the next page and day.