Day Three (Monday, 4-14-2025): Healthy Forests and Roaring Falls

Early morning has broken like the first morning and skies remain clear. Leaving ECCO for another long day, we retrace our route north along Hwy 41 up through the forest with extensive multiple burns and past Wawona on our return to Yosemite Valley. Along the way, Chris Cameron tells some captivating seeds stories from a seed’s perspective: After waiting patiently in the soil for so long, should I germinate now? Did I wait too long or am I sprouting too early? Conditions will have to be perfect if a little seed like me will survive to become a giant tree.

We stop to identify some conifer tree species (comparing the sizes and shapes of needles, bark, cones, and seeds) common to this higher elevation, from ponderosa and Jeffrey pine, to incense cedar, Douglas fir, white fire, and even a few sequoias. Since this is our forest science morning, we review a few timber terms shared by our California Conservation Corps classmates: limbing refers to cutting the lower limbs of the tree: binding is when the saw gets pinched or jammed in the wood; bucking cuts the tree into manageable log sections suitable for processing; and chipping produces mulch. We also reviewed the more recently researched underground world of mycorrhizae, the symbiotic relationships (nutrient and water exchange) between plant roots and fungi. The fungus extends the plant’s root system, absorbing nutrients and water from the soil, which it then transfers to the plant. In return, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. It’s a nonstop network of interconnected communication and cooperation down there.

We meet Yosemite’s renowned and sometimes embattled forest expert and National Park Service Ranger, Garrett Dickman, in Yosemite Valley, near the base of Bridalveil Fall. He summarized the predicament we’ve created in Yosemite and in forests throughout the western states. A combination of habitat destruction, past short-sighted timber harvesting, invasive nonnatives, fuel buildup from fire suppression, and climate change is now threatening the very survival of our forests and surrounding plant communities. Recognizing these past mistakes was one hurdle; fixing them is proving to be much more difficult. More than a decade of wildfires-turned-appalling conflagrations were the wakeup calls that brought us to this turning point. You will find other stories on this website that follow these catastrophes, but Garrett Dickman provides us with an expert update and summary.

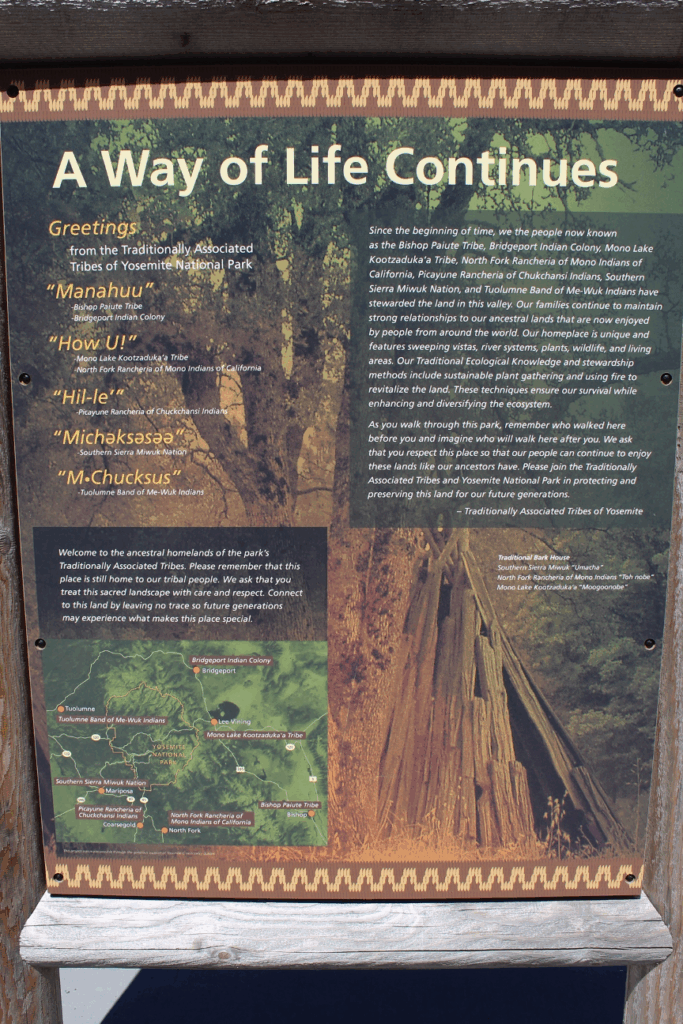

California’s fire ecology story starts with thousands of years of traditional ecological knowledge that encouraged growth of tubers, grasses, and other nutritious species more common to meadows and other open areas with abundant sunshine. It is estimated that Native Americans burned Yosemite Valley every 1-5 years; tree rings and other evidence suggest sequoia forests experienced fire every 10-15 years before the Spanish and later American settlers arrived. Some older giant sequoias have lived through up to 300 mostly low-intensity fires during their lifetimes. More recently, nearly a century of snuffing out fires encouraged a massive buildup of fuels in our forests. Enter UC Berkeley School of Forestry Professor Harold Biswell (retired in 1973), who first advocated for the use of prescribed burning. Though he was first met with resistance from some foresters and the public, his methods to reintroduce natural fire cycles for healthy forest management were accepted policy by the late 1900s. Biswell knew then what researchers have learned since: that most Yosemite and Sierra Nevada climates and plant communities are too dry to efficiently decompose downed wood and other fuels, making fires essential for clearing groundcover and leaving ash to add nutrients in the soil. Fire also helps to control diseases and pests, while maintaining a healthy mix of well-spaced species, such as Yosemite’s black oak, with its calorie-rich acorns.

Fire suppression and poor logging practices of the past left us with very dense stands of smaller chimney trees and other “ladder” fuel buildups that encourage ground fires to become catastrophic crown fires that burn through forest canopies. Introduce flammable nonnative invasive species, add climate change, and we have the perfect storm. It has become the big western US forest management dilemma: How do we return to the natural fire cycles of the past? Details and politics get in the way. Only about 1% of prescribed fires eventually escape to get out of control, but obstacles include very narrow time frames during the year when prescribed fires can be used here (around October/November in these parts of the Sierra Nevada), and then only during specific weather conditions. Add other concerns about air quality, tourism, endangered species, state, local, and federal regulations, and limited labor and resources, and it becomes obvious that we are not going to burn ourselves out of this corner in the next few decades.

Nevertheless, the Yosemite Conservancy is working with the National Park Service and native tribes to bring back that traditional ecological knowledge in the form of expanded prescribed burns. But a sense of urgency calls from our forests, which is why thinning them may be one of the fastest and most efficient ways to reset them back to their natural cycles. And that is why experts such as Garrett Dickman have come under fire: saving the trees and entire forests may require selectively cutting some trees since mechanical thinning can mimic some effects of prescribed fires, resulting in healthier mixed conifer forests. The Washburn Fire in July, 2022, serves as one example of how prescribed burns and other fuels reduction treatment might save our forests. It started near Mariposa Grove’s beloved giant sequoias (some are more than 2,000 years old), but previous prescribed burns there helped to steer the fire away from the big trees as it expanded into Sierra National Forest to burn nearly 5,000 acres.

We’ve highlighted this short movie, Last of the Monarchs, in previous stories, but it is the perfect relevant summary here.

Our morning is complete with a walk around the base of a roaring Bridleveil Fall. Here, we can see signs of NPS forest management and we can thank the Yosemite Conservancy for providing access and trails to watch the mist swirling in giant eddies around the fall.

Deciduous trees such as bigleaf maple are just starting to bud in April. Taller conifers are seen in the background, as they point toward the morning’s crystal blue sky, perhaps to demonstrate the diverse mix of species common to healthy woodlands and forests.

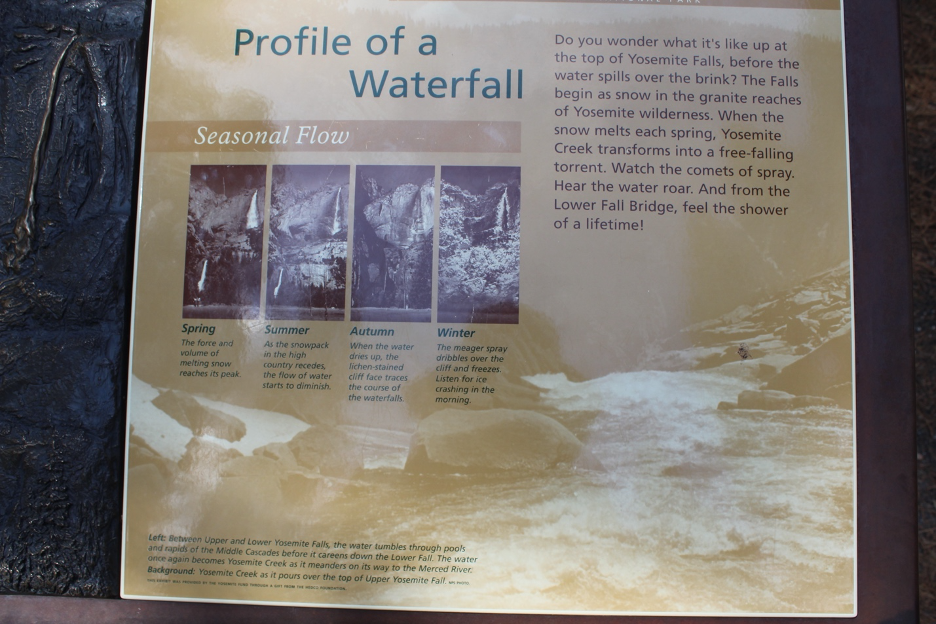

Following lunch at Yosemite Village, we took the trail to Yosemite Falls. (This reminds me of one our Santa Monica College field classes from decades past, when biologist/naturalist Walt Sakai and I led our students all the way to the top of Yosemite Falls. We won’t attempt such a climb on this trip, but if you are tempted, you’d better bring plenty of water and prepare for a serious workout on the numerous trail switchbacks.) Yosemite Falls is sometimes advertised as the tallest in North America and one of the tallest in the world, but that includes the upper, middle, and lower falls combined (2,425’, or 740m). Parts of it freeze into giant ice cones in the winter. It usually becomes a roaring spectacle demanding attention by April through June but it dwindles to a trickle by late summer, after high elevation snowpacks have melted away. This is also a good place to study streamflow/discharge along Yosemite Creek, which flows from the falls, where spring’s cascading whitewater often turns to a trickle by August.

We searched for signs of life in the stream and under the rocks. Though they may be difficult to find, there are plenty of critters hiding in the frigid waters. Some of the invertebrates might even be the next meal for the more noticeable American dipper, or water ouzel (Cinclus mexicanus). A thick layer of down and waterproof plumage keeps these water-loving birds warm in the coldest of Sierra Nevada streams and rivers. They even have an extra eyelid or membrane that acts like a goggle to see underwater, and scales to cover their nostrils. Observe their peculiar habits of bobbing on rocks and diving in for a meal. My last sighting was up in Sequoia National Park.

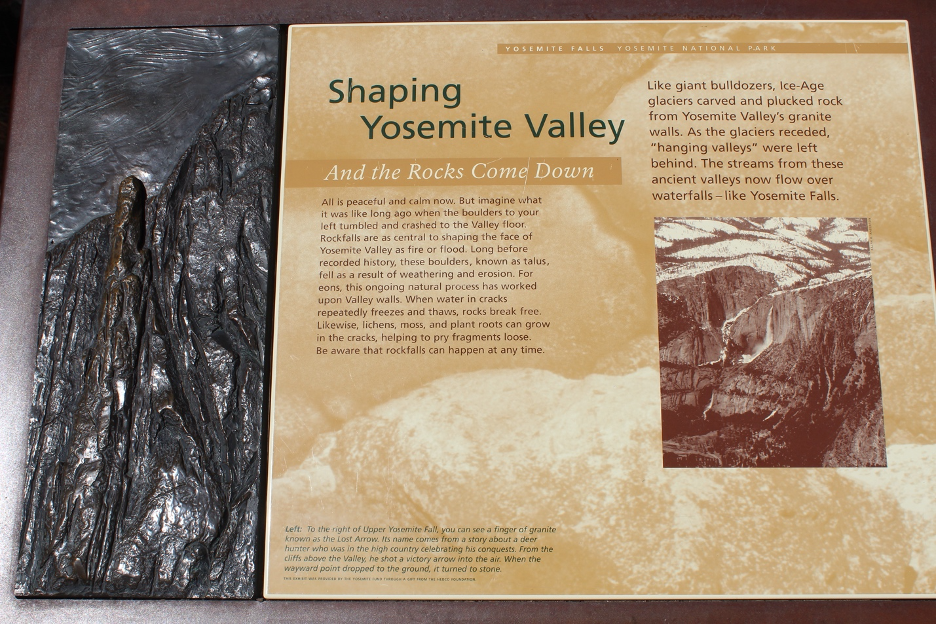

Along the trail to the base of the falls, you might notice giant boulders that have tumbled down the cliff after centuries of chemical and physical weathering had finally dislodged them. Some of them are hidden behind big leaf maple, dogwood, and other deciduous trees that are just budding in April and will cast precious shade through the hot summer months. Building afternoon cumulus in our sky dome announce that high pressure is gradually yielding to the little upper-level low spinning toward us from the coast. Big weather changes are on the way.

We load into the van and head back to ECCO for dinner. There, our bird experts spot and identify a few species that include mallard ducks, duck-like buffleheads, and yellow-rumped warblers in the big pond, surrounded by a few trotting wild turkeys. The bird pond party eventually quiets down after sunset as overnight temperatures will eventually dip down into the 40s F, which is pretty typical for April.

Click (below) to the next page and day.