Day Four (Tuesday, 4-15-2025): Cliffs, Bats, Fires, Technology and Botany

The early morning sky signaled continuing gradual change with a layer of thickening high cirrostratus and a few cumulus clouds, all drifting from south to north under the influence of the counterclockwise circulation around a cutoff low approaching from the west. Daytime temperatures would drop a few degrees compared to our first days.

After we shared breakfast and packed our lunches (there would be no excuses to go hungry during this week!), our driver Jim shuttled us the short distance to Wawona, turning off Hwy 41, toward the UC Merced Yosemite Field Station. Along the way, we discussed “mast acorn crops”, when bumper crops of acorns are (sometimes mysteriously) produced in one random year. This may be a strategy for the trees to produce far more acorns than wildlife can consume so that more acorns can geminate into trees during just one season. Regardless, there may be specific weather conditions within particular microclimates that can set off one of these masting years within local woodlands. A mature oak tree (several decades old) is capable of producing 10,000 acorns in one year. Mast years bring great abundance for today’s wildlife (even changing their migration patterns), just as they were for Native Americans dependent on acorn crops.

This is where we learn from Dr. Breezy Jackson, Director of the Yosemite and Sequoia Field Stations. This field station (in operation for about 20 years) is part of the UC Reserve System and is open to all types of academic research in cooperative agreements between the UCs, CSUs, and state and national parks. Such interdisciplinary/transdisciplinary field studies included about 170 different research projects last year alone. The field station not only allows students to live where they are researching, but such emersion has demonstrated that students who study in the field perform better in school and are more likely to graduate. (This confirms what I learned while teaching students in my field classes at Santa Monica College, where I insisted on incorporating field work into the curriculum: students were not only more motivated to learn through real world experiences, but such experiential learning left exceptional memories and made lasting positive impacts on their lives and careers.)

Among the many hats she wears, Director Breezy Jackson is an expert on cliffs. She uses the term “rewilding” to describe how we can turn people back on to nature and science. She cites her increased “wisdom and clarity” as she matures and quotes experts such as forest scientist Tamir Klein’s statement about how plants “can inform, but not decide”, noting how plants can perceive and respond to their environment, but they can’t make conscious decisions as humans do. Breezy hosted the first Cliff Ecology Conference here, where fifty scientists gathered to present their research on the ecology of cliffs across the country and around the world. You would be amazed to learn what is going on up on those cliffs, from Yosemite and beyond. Here are some excerpts from the cliff expert. Besides those lichens that help stain the rocks, you will find trees growing into cracks and cavities, nesting peregrine falcons, swifts, raven, golden eagles and other bird species, monkey flowers, western fence lizards, various insects (including aquatic insects near the seeps), mice, wood rats, tree frogs, rattlesnakes, and king snakes.

Yosemite is also home to 17 species of bats. Our bat colonies in the West are small compared to the East Coast. Bats are usually right-handed like humans, but about 20% are left-handed. Yosemite bats range in sizes from a tiny 3 grams (canyon bats) to up to 20 grams. Spotted bats are the ones with huge echo-locating ears. Mexican freetail bats are fastest in flight, second only to diving peregrine falcons. Cave bats are particularly cryptic, so researchers are still learning about them. In contrast to species that put very little work into raising their young (such as trees and their seeds, insects and their eggs, fish and their eggs), bats and other mammals that live longer put a lot of time, energy, and care into parenting. Birthing females catch newborns with their rear netting. All Yosemite bats are insectivores, scooping insects into their mouths during flight.

About 1/5 of sick bats that have been brought in to the field station test positive for rabies, so the rabies rates in healthy bats must be much lower. Researchers have been using caution since it was discovered that COVID can be transferred between humans and bats. And cavers must be cautious since it was discovered that brown bats living in the US have developed a fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) from Europe that can kill 90% of bat populations after being introduced into particular caves. Our schedule requires us to leave more bat research and stories to other naturalists at another bat time, which proves again that when we answer one question about nature, we discover many more questions and unanswered mysteries.

New technologies are helping to solve nature’s puzzles. For instance, radio telemetry towers (Motus towers) are being used to track bats, birds, and insects as they fly and move around. Lightweight tags attached to the animals transmit radio signals to the towers, allowing researchers to study animal behaviors. Many thanks to Breezy, but it’s time to move on to make new discoveries.

We pull of off Hwy 41 near the little general store on Forest Drive. We continue to the end of the road, where we eat our lunch on a big log and then set out on the Wawona Swinging Bridge Trail. During our walk to the bridge, Chris Cameron summarizes the essentials of weathering and decomposition that produce soil profiles. He emphasizes the importance of FBI (fungi, bacteria, and invertebrates). We poke and prod through the most fundamental soil profiles starting at the surface: litter, duff, humus, topsoil, subsoil, and finally bedrock at the bottom. A loud Steller’s jay rummages into the soil profile and calls out to remind us how these aggressive scavengers help disperse seeds that sprout to become new plants in a healthy forest. These omnivores with their beautiful feathers that reflect blue light are smart enough to mimic sounds that include other animals.

The trail to the bridge along the South Fork of the Merced River (designated a wild and scenic river as it flows out of the high country) offers opportunities to compare recovery after two fires. The 2017 fire (near the height of the megadrought, bark beetle infestations, and millions of Sierra Nevada tree mortalities) burned south-facing slopes to our left, across the river; later, the 2022 fire burned north-facing slopes to the right of the trail. What a great location to research how slope aspect influences light and heat exposure, which helps determine the rate of regrowth following two different fires from eight and three years ago. There is a popular swimming hole here, but the water and weather are still far too cold to test the swirling whitewater. This section of the river also experiences enormous variations in discharge that have ranged from 2.15 cubic feet per second (July 2014) to more than 1,000 cfs during spring runoff periods. (A cubic foot is about the same volume as a basketball filled with water.) It is also a good place to review how discharge is estimated by measuring the average cross sectional area of the stream and then multiplying it by the average water velocity of water across the stream (Q = A x V). NOAA has operated a stream gauge just downstream from our location. You can find the most recent stream stage at this site.

Both sides of the river and foot bridge are good places to use our phones to help us identify various species using iNaturalist, especially since the fires opened the formerly denser forest to sunlight and diverse wildflowers. Species identification and research has become much faster and easier compared to decades earlier, when I started leading my field classes through just about every imaginable environment and field experience. Dive in with caution: these new innovations have become invaluable tools, but they will never fully replace our accumulated knowledge that helps trained naturalists sense whether the technology can be trusted. Today, we can just take the photo and let image recognition technology start the process. Here are two links for starters:

https://www.inaturalist.org/

https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/seek_app

This article summarizes some history and recent iNaturalist applications using AI in California and beyond.

Here’s another article that shows how citizen science is helping us better understand the biodiversity that surround us.

While each student used the technology to identify and share particular plant species, I ran my own tests. They included common shrubs that grow extensively around Wawona and are easy to identify, such as Mountain Misery or Bear Clover (Chamaebatia foliolosa). The app also identified a perennial non-native grass called Bulbous bluegrass (Poa bulbosa); Brown-eyed Wolf Lichen (Letharia columbiana), is common to subalpine forests around here; Soft Rush (Juncus effusus), is also common here in wet areas along the South Fork of the Merced River; and there was a 78% chance that we correctly identified Henderson’s Shooting Star, AKA Mosquito Bills (Primula hendersonii). Whether you consider this serious citizen science or a nature game, it’s so fun that it can become habit forming.

Before returning back to ECCO for dinner, we will take a break at the little Wawona General Store where Forest Drive meets Hwy 41. This will be our last sunny day for a while as this afternoon and evening’s sky dome is increasingly decorated with a mix of clouds that announce the approach of that pesky cutoff low from the west.

Our typically long action-packed day ends with an amazing two-hour high-energy guest: biologist and naturalist Shirley Spencer, “Educator, artist, naturalist, and author inspiring environmental stewardship through teaching, illustration, and conservation.” She arrived armed with informative props that display a wealth of botany basics to get the conversations started and she also shared her many colorful paintings. Her diagrams and intro include the typical (and necessary) summaries of the differences between gymnosperms (open naked seeds) versus angiosperms (closed seeds that are most common) and monocots versus dicots. She included diagrams illustrating the different flower parts and leaf shape descriptions, such as pinnate versus palmate.

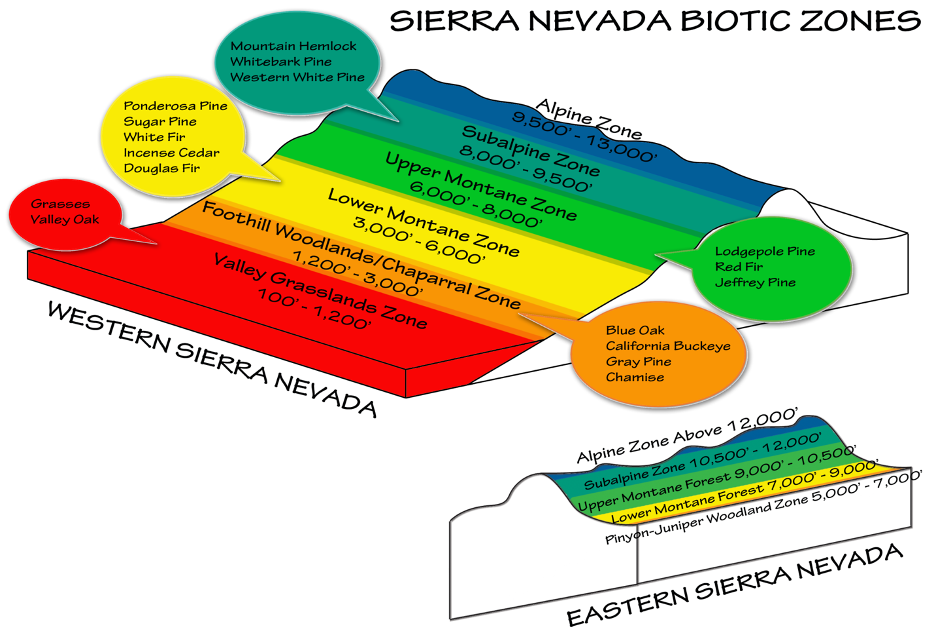

Shirley then dives into her discussion, recognizing the uniqueness of the California Floristic Province and asking what makes the Sierra Nevada so special: proximity to the Pacific Ocean, elevation gradients, and latitude. This launches us into a survey of Sierra Nevada’s vegetation zones, which are similar to the life zones we have highlighted on this website and in my book. (I also wandered into them on the first page covering my first day of this story.) Here is a good diagram from Reflections of the Natural World by Jim Gain.

Here is a summary of how Shirley Spencer describes these zones:

Grasslands: Mainly introduced grasses have replaced the prairies at these hottest and direst lowest elevations that define slopes up from the Central Valley. They are occasionally interrupted, especially along stream courses, by valley oak, Fremont cottonwood, western sycamore, and willow, where trees’ roots can find groundwater.

Foothill zone: Blue oak (with its blueish leaves), interior live oak, redbud, California buckeye, manzanita, and that scraggly gray pine with long needles and huge cones. In less disturbed foothill grasslands and woodlands, you might find vernal pools, with rings of plant species that grow closer or farther from the center of the ephemeral pools, depending on their drought tolerance. This is particularly true on top of volcanic tablelands, where ancient lava flows resistant to erosion now protrude above surrounding landscapes.

Lower Montane or Transition Zone: Canyon live oak, mountain whitethorn (ceanothus), western azalea, mountain dogwood, alder and deciduous trees that may include black cottonwood and black oak. Conifer trees that include ponderosa pine (with prickly cones), incense cedar (scale-like leaves and tiny cones with only four seeds), and occasional white fir and sequoias at more moist higher elevations.

Upper Montane: Cooler, wetter and denser forests with largest diameter trees in the Sierra Nevada. White fir, Douglas fir, sugar pine (with the longest cones), sequoias, Jeffrey Pine (bark cracks smell like vanilla or butterscotch and cones are less prickly than ponderosa), huckleberry, oak, dogwood, bush chinquapin, pinemat manzanita, red fir, and lodgepole pine at higher elevations.

Subalpine: Where the most snow falls, such as around Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite high country. Mountain hemlock (tall and slender with small cones and a crown that bends down to shed heavy snows), western white pine (with a larger curved cone), western juniper. Quaking aspen is more common on the east side of the range. These attractive aspen trees grow in groups with connected rhizomes within wet soils. Their leaves shake and wave in the breeze, perhaps to occasionally let sunshine down to lower leaves.

Alpine: Plants only have about eight late summer weeks to grow, bloom, and go to seed after the snowpack melts and before the first hard freeze and snowfall of the next season at these highest elevations. The hardiest prostrate plants may include whitebark pine (which grow slow near the ground), arctic willow, and colorful flowers such as columbine, and alpine gold.

Down the eastern rain shadow slopes: Taller aspen grow near water sources where snowfalls aren’t as heavy. Western juniper, Jeffrey pine, yellow willow, pinyon pine, rabbitbrush, sagebrush.

Shirley wraps up this session with a discussion about how many invasive species are here to stay, but they aren’t considered noxious until they are out of control. Honeybees and eucalyptus are examples of nonnatives that we have purposely introduced.

The night ends mostly overcast with only a few stars sneaking out as that low pressure system approaches. The additional moisture and clouds will keep temperatures a bit warmer overnight, but make tomorrow a lot cooler.

Click (below) to the next page and day.