Most of you have already seen the inconceivable destruction on local news and social media. After surveying post-fire landscapes from Malibu to Pacific Palisades, and from Eaton Canyon to Altadena, I am sharing images that help summarize the extent of devastation just about a month after the conflagrations. The two previous stories on this website summarize conditions that led up to these historic disasters.

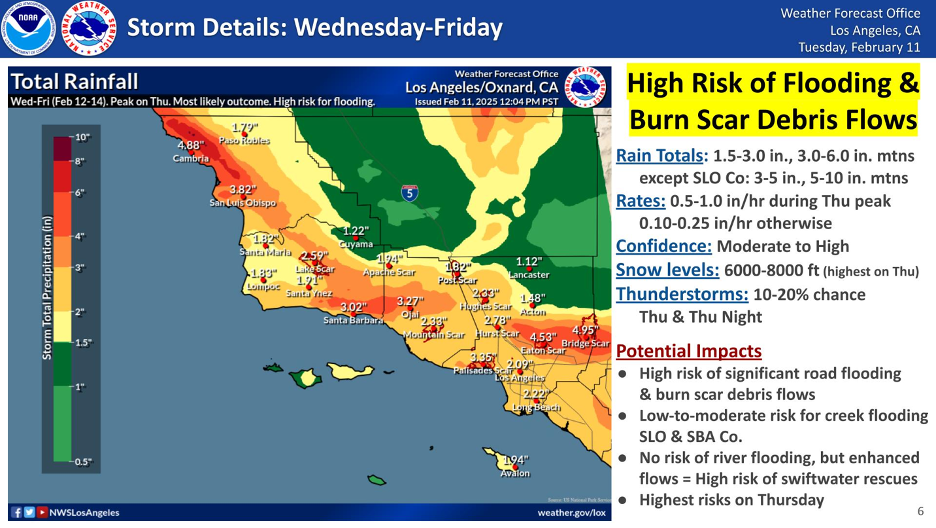

There are at least five main themes threading through these images and videos. First, the steep slopes, loose materials, and stripped ground cover leave landscapes vulnerable to any significant precipitation, especially heavy downpours. Such mud and debris flow threats will continue with every rain event until sometime in April, when our normal annual wet season usually ends. Then, there’s always next year. Second, note the haphazard and unpredictable burn patterns that determined which homes, neighborhoods, and businesses were destroyed and which survived the firestorms as they swept through. Third, many of you may have to strain to recognize what is left of some iconic SoCal landscapes and neighborhoods seen and celebrated in countless films, TV series, commercials, and videos over the decades. Fourth, note how the wildfires didn’t discriminate, ravaging diverse neighborhoods from rich to middle- and working-class. Finally, we will end with a few articles that summarizes how we built ourselves into this disaster-prone corner.

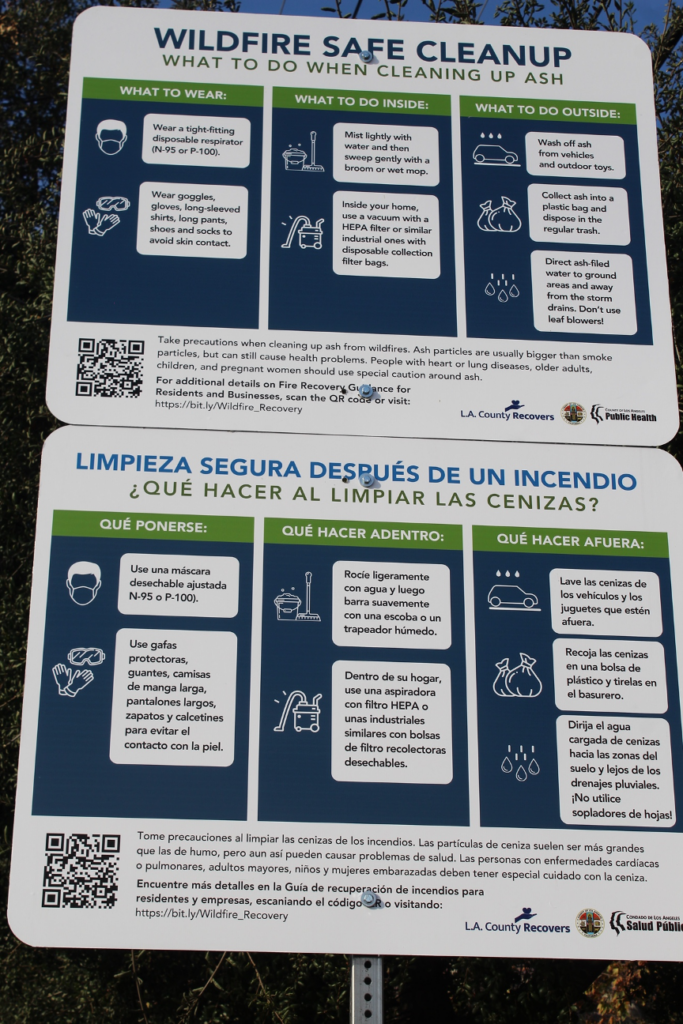

I am also sharing the following images to confirm that there is no reason to visit the devastation, since you are not likely to discover anything new that hasn’t already been displayed multiple times in the media. And there are at least five reasons (yes, another list!) to NOT go wandering into the Palisades or any other recently burned areas. First, PCH and other roads along that entire coastline and into the Santa Monica Mountains will be subject to closures at least through what remains of our rainy season. Second, even if you find an open road, the one-lane traffic gridlock is a frustrating waste of time. Third, you can’t turn off or even briefly stop without getting cited (at best) or arrested by an army of law enforcement officers. Fourth, these are toxic landscapes that pose a host of health hazards and dangers to visitors. Finally, cleanup and construction crews are working hard to rebuild essential infrastructures throughout Pacific Palisades and Altadena. The last obstacles they need are selfie crowds getting in their way and impeding their progress. So, as you view immediate post-fire images here and in the media, know that there is nothing more to see as the cleanup progresses.

The Mountain and Franklin Fires as Warnings

Two months before the mass destruction in LA County, the Mountain Fire erupted in nearby Ventura County. Strong Santa Ana winds (as predicted) also fanned this blaze that consumed nearly 20,000 acres and 243 homes and commercial structures. Just about one month later, the Franklin Fire ignited on Dec 9 and quickly grew to 4,000 acres as powerful Santa Ana winds (again, as predicted) funneled through the Malibu Canyon wind tunnel and toward the beach. In contrast to the Palisades and Eaton fires, it only destroyed or damaged 48 structures, including a few homes. For instance, Pepperdine students and staff were forced to shelter in place as the flames raced around them, but the campus survived. Heroic efforts by savvy firefighters helped to contain the damage, but it also helped that Malibu Canyon had burned just several years earlier. Researchers use the historical record to estimate that this area has burned in wildfires on an average of two times/decade (the entire Malibu coastline is impacted by even more frequent fires), which decreases potential fuel build ups. But such frequent fires also encourage the invasion of nonnative species that are more flammable, leading to even more frequent fires and accelerated wildfire growth. By most Decembers, our fire season has been snuffed out by winter rains. (Rains brought welcome relief months earlier in the previous two years.) But this year’s long drought dragged, incredibly, into late January, through the middle of our rainy season. The stage was set for relentless Santa Ana winds that would take over from there. As finger pointing mounts about details and specific responses to these wildfires, here are a few facts to keep the debates honest.

Unraveling Some Misconceptions

First, these firestorms had nothing to do with water diversions from Northern Cal. The state had just experienced two consecutive banner wet years that finally broke our two-decades-long megadrought and then competed for the wettest on record. Nearly all of our reservoirs were recently filled and our state water projects overflowed with more water than we could distribute and use. Unfortunately, the several months of recent unprecedented drought that followed those storms dehydrated the biomass that accumulated during the previous two rainy years, providing abundant dry fuels for ignitions. Our state’s water diversion and storage projects were performing well, but were surrounded by dehydrating Mediterranean plant communities interspersed with encroaching human developments, all enduring prolonged and historic Santa Ana winds. Only the details were left to debate in this landscape made for disaster, where millions of Californians found themselves within an expanding wildland-urban interface.

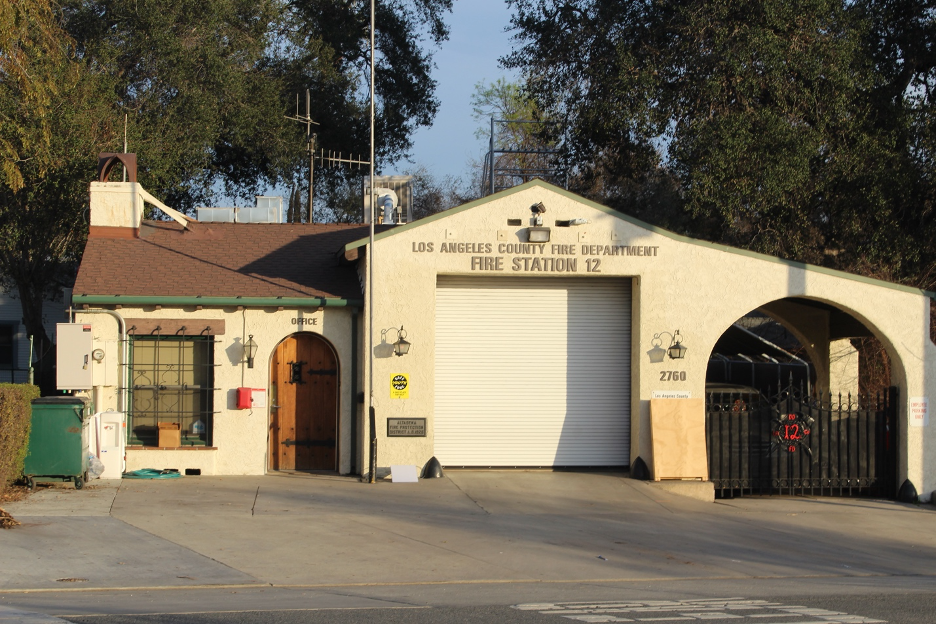

As example, the one relatively small reservoir that served Pacific Palisades had been “taken out of service to “meet safe drinking water regulations,” the DWP said in a statement. A tear in the reservoir’s cover made the water supply subject to contamination, the Los Angeles Times reported, leading the agency to drain it in February.” … (meaning last Feb.). This left three one-million-gallon tanks to serve the Palisades, which were more than adequate for providing safe drinking and irrigation water and for fighting multiple structure fires. They obviously weren’t enough for fighting the stampeding wave of flames. Many fire hydrants designed to battle structural fires and smaller brush fires were also inadequate for such a colossal bombardment. Such details will be the focus of investigations into how heroic firefighters could have had a better infrastructure to support their efforts as winds peaked over 70mph. Many scientists, engineers, and firefighters question whether ANY water infrastructure could have made much of a difference in this firestorm fanned by wicked winds that also hampered air assaults. This was also the case in the Altadena inferno, where fist-sized burning embers were being blown up to a mile ahead of the fire front.

Finally, for those of you not familiar with SoCal, our wildfires that spread into neighborhoods did not (and usually don’t) erupt and spread from a “forest’, but from our coastal sage scrub, chaparral, and related plant communities that help define our Mediterranean climates and ecosystems; so, “forest” management is not relevant. We’ve heard suggestions that our plant communities should be destroyed to protect nearby developments, but that would require clearing at least half-mile strips surrounding every structure. This would represent habitat destruction on a massive scale, accelerate species extinctions in our unique California Floristic Province, and wipe out thousands of natives and endemics. And they would likely be replaced by invasive nonnative grasses and other highly flammable biomass that act as conduits for fires. Proposed “clearance” on such a grand scale would also result in more frequent and catastrophic floods and debris flows out of these disturbed, vulnerable landscapes during nearly every rain event. We’ve seen this movie and its sequels play out too often: the very plant communities that protect us by absorbing floodwaters and stabilizing our slopes, provide habitats for a dizzying array of plant and animal species, and represent open spaces where we can appreciate and study our natural history, can suddenly turn on us by sending their burning embers.

Our careless developments and dysfunctional relationships within these very ecosystems that we cherish have been debated for decades and these difficult debates will (and should) continue into the future. It took many decades to build ourselves into this worst-case scenario fire corner. For more objective analyses and some back-to-reality answers, check out the links that follow my aftermath images, at the end of this story. As you view the following images, please remember that they are what remains of thousands of families’ hard work over many decades … shattered lives, hopes, and dreams incinerated into ashes.

Before we skip inland over to Altadena and the Eaton Fire aftermath, here’s just one example of what was lost in the Palisades. Some folks who couldn’t afford to buy a house on the beach opted for a mobile home and also lost everything. This real estate description paints a pretty clear picture of life there in the before times:

16321 PCH

Pacific Palisades Bowl Mobile Home Estates

Roughly $500,000-$1 million

What’s special

BREATHTAKING DRAMATIC OCEAN VIEWS MARBLE BACKSPLASHES CUSTOM CABINETRY EXPANSIVE MASTER SUITE SEPARATE PANTRY ROOM QUARTZ COUNTERTOPS HIGH-END FINISHES

MOVE-IN READY! This stunning, new construction custom-designed, 2-story beach home is perfectly positioned across from the iconic Will Rogers Beach in Pacific Palisades, offering an unmatched combination of luxury, convenience, and coastal beauty. The home’s prime location provides breathtaking, dramatic ocean views from Malibu to Catalina Island, visible upon upper level. Entering, you’ll be enveloped by a bright, open ambiance that seamlessly merges indoor and outdoor living. Natural light floods the home, illuminating the carefully crafted details throughout. With 2 bedrooms and 2 bathrooms, this home boasts soaring 9-foot ceilings and elegant double-door entries that enhance its spacious, airy feel. The first floor offers a convenient bathroom, while upstairs, the expansive master suite awaits with a dual-entry bath alongside a second well-appointed bedroom. Every inch of this home has been thoughtfully curated with high-end finishes, including quartz countertops, marble backsplashes, and custom cabinetry with pull-out shelves in the chef’s kitchen. The kitchen is equipped with premium stainless steel appliances, a Shaw’s farm sink, a gas oven, vented exhaust fan, disposal, refrigerator, dishwasher, separate pantry room, and stackable washer and dryer. Additional features include central heating and a tankless water heater, enhancing both comfort and efficiency. Outside, imagine crafting your ideal outdoor retreat on a spacious 320-square-foot second-story deck, perfect for lounging and entertaining while soaking in the endless ocean views. Dedicated two parking spaces and guest parking available, and 24-hour private security patrol. Residents enjoy access to premium community amenities, including a large heated pool, hot tub, billiards room, and a recreational area. Positioned near Palisades Village and top-rated schools, this home combines luxury with practicality. Cross PCH via a nearby crosswalk for quick beach access, and enjoy low space rent of $970/month with rent control, plus the added financial benefits of no annual property taxes or HOA fees. Purchase includes city and coastal approved plans for custom built deck for convenience.

Eaton Fire (Altadena) Aftermath

Altadena is only about 25 miles (straight line distance) northeast of the Palisades, but most locals would tell you that they seem worlds apart. It can take about an hour (depending on traffic) to navigate from one to the other and you might feel that you’ve been transported hundreds of miles from a beach once you finally arrive in Altadena. Adjacent to Pasadena of Rose Bowl and Parade fame, Altadena is nestled on the edge of the San Gabriel Valley at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains. It looks up to the abrupt steep slopes (once covered by chaparral and woodlands) that tower all the way up to Mt. Wilson, all being lifted along a series of active faults. Cooling sea breezes often struggle to make it this far inland during hot summer days when the smog can get caught below the infamous inversion and jammed against the mountains. By contrast, during winter, this region can resemble a warm, sunny paradise when their spectacular snow-clad mountains point into crystal clear blue skies.

Compared to the Palisades, Altadena displays cultural diversity that is more representative of California. This is partly because the neighborhood known as Altadena Meadows was one of the few communities where black families were allowed to settle, back during the days when segregation was enforced and redlining ruled. Thousands of working- and middle- class families worked hard for decades to improve these neighborhoods, often hoping to pass their investments on to future generations. I learned about Altadena when I frequented Pasadena, enjoyed hikes into the local canyons, and developed a working relationship with the heroes of the Eaton Canyon Docents, led by Diane Lang. There at the renowned Eaton Canyon Natural Area and Nature Center, we trained docents to guide school groups and visitors eager to learn about the natural history of these treasured Mediterranean landscapes. We learned a lot of science while exploring the natural systems and cycles that rule our world and we soothed plenty of nature deficit disorders.

All of it has been lost. Surrounding slopes, the nature center, homes of some of the docents (including Diane’s house), much of Altadena and more of Altadena Meadows has burned to the ground. We always studied and understood how fire plays such an important role in these ecosystems and locals even recalled when another wildfire burst out of the mountains and burned the old nature center in October, 1993. But this fire was different, as it was fanned by the fiercest Santa Ana winds that blew burning embers a mile ahead of the front. Just as the Palisades Fire was destroying everything in its path all the way to the beach 25 miles away, this fire would not stop at the base of the mountains. It was blown ahead right into the city, destroying entire neighborhoods that most people thought were far removed from wildland fires. Within one tragic day and night, Altadena and Pacific Palisades were connected in ways that some could not have imagined. The two previous stories on this website summarized the conditions that led to these tragedies and why they exploded out of control. But perhaps the key word is control. Nature’s awesome power reminds us that we cannot separate ourselves; we are just parts and players within these natural systems and cycles.

In case you missed it, positive messages and messengers of hope are gradually rising out of the ashes in Altadena. Here’s one example of a local artist who is making a difference in Altadena Meadows. It includes some video from the air: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nYPmFS84SiA

This interview confirms how a reality check and building paradigm shift is necessary if we expect to develop more fire-resistant communities. (Thanks to Bill Patzert for sending it along.)

This is a very thorough summary of the corner we have built ourselves into, and our long LA fire history. Thanks again to Bill Patzert for sharing.

Here’s another LA Times article that sums up the problem and some potential solutions.

This Malibu Times article is dated, but leaves us with a rough fire history up to 2007.

If you’re in to geospatial imagery, check out these before and after NASA EARTHDATA images captured in January, 2025, by the MSI instrument aboard ESA’s Sentinel-2A platform.

This camera shows the advancing smoke and flames that eventually consume a Pacific Palisades neighborhood.

This video (it is a long journey) takes you up from PCH through Topanga Canyon in the aftermath to see what burned and what escaped the flames, illustrating why any substantial rain will produce destructive mud and debris flows. It was filmed on January 17th.

Here is a Pacific Palisades Aftermath Tour.

Let’s hope this will be THE END of our disaster stories for a while.