Here is a different story about the tropical storm that made national news and will live long in California history. Hurricane Hilary was exceptional only for the path it took and its fast pace. Otherwise, this could have been just another example of the major hurricanes that form off the southwest coast of Mexico from June through October each year. (Last year on this website, we summarized some tropical cyclone science and their history of mostly avoiding California, as we followed a near-miss tropical storm Kay. We wondered out loud which future summer season weather pattern might finally send such a storm directly to us.) This year, had Hilary eventually drifted west out to sea like so many of the more typical tropical tempests, most weather watchers wouldn’t have given it much notice. Even if it had drifted over Mexico when it was a powerful hurricane, most Californians may not have paid much attention, much less remembered it. It’s funny how our perceptions of weather events and natural disasters are shaped by our intimate experiences with them and our distances from their impacts. And here I am writing about the kind of storm I and others experienced for the first time after several long decades of observing California weather events. Our big summer of 2023 SoCal weather story might leave folks from Mexico and parts of the southeastern U.S., where hurricanes remain dreaded threats throughout their warm seasons, wondering why Hilary was such a big deal. (Think Hurricane Idalia as it slammed into Florida about ten days later.) We know that every storm is different, but Hilary stands out for a number of reasons besides the obvious one: we’re not supposed to get such storms in California.

Follow this series of NOAA maps from August 16, four days before landfall:

It all started several long days before Hilary’s August 20 landfall, when the National Weather Service recognized yet another band of showers and thunderstorms forming off Mexico’s southwestern coast. Models forecast favorable conditions (including warm ocean water temperatures) supporting the rapid development of a tropical cyclone that would likely become a major hurricane. And this one would be different. Longer-term models suggested that the strengthening storm would drift northwest and up along the Baja coast toward southern California. Days later, by Thursday, August 17, the National Weather Service was already warning us about Hilary, which was churning over the warm waters south of Baja. Here is an excerpt from the Forecast Discussion issued by the National Weather Service on that afternoon, still three days before the storm swept through:

National Weather Service in San Diego at 152 PM PDT Thu Aug 17 2023:

“Hurricane Hilary will continue to progress north off the coast of Baja, bringing widespread rain and the potential for flash

flooding across Southern California late Saturday through Monday.”

AND…

“Hurricane Hilary is expected to rapidly intensify as it moves northward up Baja

California, then weakening as it hits colder waters in northern

Baja.”

AND…

“Regardless of the exact track and intensity of Hilary, which

could continue to change in the coming days, it will bring a

substantial surge in moisture into Southern California, with heavy

rainfall and a high potential for flash flooding, especially for

the mountains and deserts. A Flood Watch has been issued with the

afternoon forecast package for all areas Saturday through Monday.”

AND…

“Current forecast rainfall amounts Saturday through Monday:

Coast: 2 to 2.50 inches

Valleys: 2.50 to 3 inches

Mojave Desert: 3 to 4.50 inches

San Bernardino County Mtns: 4 to 6 inches, locally up to 8 inches

on the eastern slopes

Riverside and San Diego County Mtns: 4 to 8 inches, locally up to

10 inches on the eastern slopes

Lower Deserts: 5 to 6 inches”

Follow these NOAA images from August 17:

Fears of damaging coastal winds and a possible storm surge would never be realized in California since it came ashore south of the border. However, final rain totals would confirm NWS predictions. By Friday, August 18, as predicted, Hilary was already a major Category 4 hurricane, but why were forecasters so confident that it would be steered toward the north-northwest and into southern California within just two days? We can partially blame that humongous, stubborn, and equally historic high pressure system that wobbled and expanded above the southern U.S., producing record high temperatures that tortured Texans and surrounding regions through most of the summer. Winds circulating clockwise from it were streaming from south to north over the southwestern U.S., on the far western edge of that high. These southerly winds were further enhanced by another unseasonably stubborn system: low pressure sitting just off the California coast. As winds were spinning counterclockwise into that low, southern California was positioned on its southeast edge, further encouraging winds to stream over us from the south and southwest. Sandwiched between these two pressure systems, southern California was located below an upper air high-velocity freeway, a perfect conduit that would rapidly push Hilary up the Baja coast and toward us.

Follow this series of NOAA images from August 18:

Those strong winds would also mold Hilary and change her behavior and impacts as she grew closer. First, the storm started moving very fast; unlike most other tropical cyclones, there was little time for it to completely dissipate as it raced over our colder waters that quickly kill most hurricanes. (Recall that tropical cyclones, powered by latent heat of condensation, require ocean water temperatures near 80° F (27° C) to develop and remain strong.) This made it likely that it would make landfall and then sprint into southern California as a dying tropical storm. Consequently, much of southern California was placed under the first tropical storm warning in history. But these strong steering winds also sheered the storm apart and tore it to pieces as it approached. The powerful updrafts, towering clouds, and tropical moisture were quickly swept to the north far ahead of the core of circulation, as it skimmed by the central Baja coast. Though moisture from the cyclone spread into Baja and southern California more than a day ahead, the eye of the deep low pressure and circulation into it became difficult to detect as it grew less organized and was torn to shreds.

Follow these NOAA images from August 19:

From the ground, a few odd weather observations would only suggest that a tropical cyclone might be approaching the Southland. Scattered thunderstorms had built up over our mountains and deserts during afternoons before Hilary arrived, but they were typical of the summer monsoon moisture that sometimes slops into southeastern California from the Sonoran Desert. The only hints that a big storm might be coming were the progressively thicker high and middle-level clouds streaming off of Hilary and over our region. Though unusual, Saturday’s gradually increasing cloud cover was not unheard of for August. After all, these could have been debris clouds drifting off the previous day’s monsoon thunderstorms over the Sonoran Desert. But, as dew points increased into the low 70s and precipitable water (the amount of water that could be drained from one entire column of air) increased toward 2 inches, we were entering uncharted summer weather territory. We can thank NWS forecasters, using their forecasting technologies, for encouraging local officials to prepare our infrastructures to manage California’s first tropical storm in more than 80 years.

Hilary raced north to make landfall on the Baja coast just south of the border on Sunday, August 20. This, along with regional wind conditions previously mentioned, helped to save the Southern California Bight from the high waves and storm surge we associate with big hurricanes that strike Florida and U.S. Gulf states. Our beaches and coastal flatlands were spared such destructive drama. While officials in coastal communities had played it safe rather than sorry, some were wondering if this big tropical storm talk was just big hype. By the time Hilary got to southern California, it was difficult to identify any organized eye or other center of circulation. But this had become two different storms. One showed up as a day of steady rains and mostly gentle swirls of winds around the coastal plains. The other Hilary ravaged slopes farther inland over the mountains and into the deserts with torrential rain and high winds. As the moist air was forced up mountain slopes, copious amounts of orographic precipitation were drained out in the form of heavier cloudbursts. So the mountains and deserts experienced the brunt of this storm that moved inland.

Follow these NOAA images from August 20 as Hilary swept into SoCal:

When Hilary swept across those massive mountain barriers that extend north from the Mexican Border, the storm became further disorganized. Sustained winds peaked at over 50 mph with gusts over 60 mph within the updrafts, downdrafts, and turbulent eddies that formed along mountain slopes. Rain totals over 6 inches were recorded from San Diego County mountains north into Canyon Country in L.A. County. Desert slopes adjacent to those mountain ranges (from near Borrego Springs to Palm Springs to Whitewater to Palmdale) received nearly as much rain, but on surfaces with little protective vegetation to absorb the water. Mud and debris flows with nowhere else to go buried roads and some neighborhoods (such as in Cathedral City), even blocking major Interstates I-8 and I-10. Within one day, Hilary’s unprecedented moisture plume continued streaming north across the Mojave and into the Basin and Range. Death Valley recorded its wettest day in history. And though officials anticipating the destruction had closed the park to visitors, about 400 people were stranded within park boundaries when roads were washed out or destroyed. Squeezed by winds streaming between those two massive pressure systems, the now disorganized moisture plume continued flowing north, delivering some precious water to drought-stricken regions northeast of Nevada. By Tuesday, August 22, Hilary was already history. Though several mountain and desert communities had plenty of digging out to do, Hilary’s quick hit impacts weren’t as catastrophic as a tropical cyclone that could have wobbled around and dissipated over us for a prolonged period.

The big rain winners were mostly at higher elevations along and near the spine of the Peninsular Ranges and up into the Transverse Ranges. The official gauge at 8,616 feet asl, near the top of the Palm Springs Tramway, recorded 11.74 inches from the storm, while surrounding regions that included Idyllwild topped 7 inches. The Baywood Flats gauge at 7,097 feet in the San Bernardino Mountains recorded 11.73 inches, while surrounding locations that included Lytle Creek also accumulated more than 7 inches. Mt. Wilson caught more than 8.5 inches. Some higher terrain in San Diego County (including Mt. Laguna) also got more than 7 inches of rain from Hilary. As mentioned, L.A. County’s Canyon Country topped out at about 7 inches. Surrounding vulnerable desert terrain and recent burn scars delivered the most damaging mud and debris flows. The next day, as Hilary’s remnant moisture sprinted farther north, the National Weather Service Las Vegas Office issued this message after debris flows sprawled across the desert floor:

“Yesterday (August 20, 2023), Death Valley National Park observed 2.20″ of precipitation at the official gauge near Furnace Creek. This breaks the previous all-time wettest day record of 1.70″, which was set on August 5, 2022.”

Follow these images from August 21, as what remains of Hilary slop far to our north:

You might say the rain losers were in the coastal flatlands of San Diego and Orange Counties (many locations didn’t make it to 2 inches), where Hilary’s moisture lacked the final lift required to ring out her tropical air masses as she simultaneously collapsed and sprinted by. Nevertheless, numerous weather stations in southern California’s coastal plains received record August rainfall in just one 24-hour period. (See the record totals in our image from the L.A. National Weather Service Office.) More than 3.5 inches of rain in one 24-hour period would make history at any time of year here in Santa Monica. But such rainfall totals in August were unheard of. Until now.

That was a quick summary of the life and times of tropical cyclone Hilary as her dying remnants staggered or rampaged through a well-prepared southern California. The good news is how this storm soaked our higher-elevation forests and lower-elevation Mediterranean plant communities that are normally dehydrating into the most dangerous fire seasons of the year. Quick deluges bumped up moisture content in our soils and vegetation and rejuvenated springs and streams that normally dry up this time of year. We can see formerly drooping and wilting plants in our gardens and on our slopes that are suddenly and surprisingly reawakened, while other species seem to not know how to respond to so much water in the middle of summer’s Mediterranean drought. Even parts of the Mojave Desert that were shielded from winter’s drought-busting atmospheric rivers were finally lifted out of official drought categories by this storm. But contrary to a few media stories, Hilary didn’t add significant new supplies to California’s water capture and distribution projects, since most of them are in northern California drainage basins not impacted by Hilary. In SoCal, a small portion of the runoff was pooled in spreading basins to percolate and recharge groundwater supplies, but much of the flash flooding was not captured.

If you’re still interested in viewing the more dramatic videos showing flood damage and destruction from Hilary, you can click one of the links that follow this story.

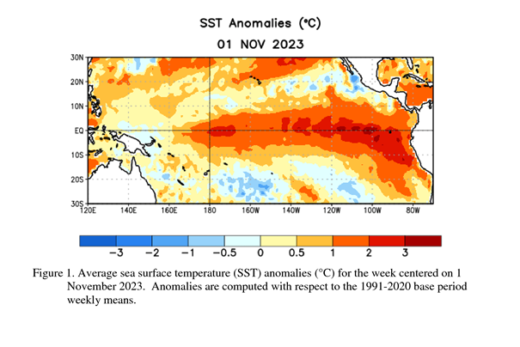

It’s been a bizarre 2023 weather year. We are plunging into an El Nino event in the Pacific, which is forecast to continue into winter. On to the next weird and wild weather anomaly… and our new weather and climate publication scheduled to appear early next year.