Another round of record-setting weather patterns swept across California as September yielded to October, 2024. In page one of this story, we follow these atmospheric anomalies and investigate their causes. Then, in page two, we explore (highlighting a recent National Weather Service workshop) how climate change looms in the background, creating a challenging atmosphere of uncertainty. (In a future story, we will explore Northern California’s November atmospheric river, southern California’s destructive wildfires, and other autumn, 2024 weather whiplashes that will live in the history books.)

Breaking October Records

Autumn is usually the season when dense high pressure builds over cooling land surfaces in the Great Basin. This annual reversal in temperature gradients also helps to reverse the onshore pressure gradients that pushed sea breezes and marine layers inland during the long high sun season. In contrast to summer, autumn brings those offshore winds that howl off the continent and toward the coast, occasionally shoving summer’s moist ocean air masses far out to sea. As the continent cools further, these descending offshore winds are often compressed to produce some of the warmest and driest days of the year for immediate coastal strips from Oregon to Mexico. You will find detailed accounts of these seasonal turnabouts in previous stories (such as our Offshore Autumn) on this website. But in 2024, some unprecedented early autumn glitches developed as September progressed into October.

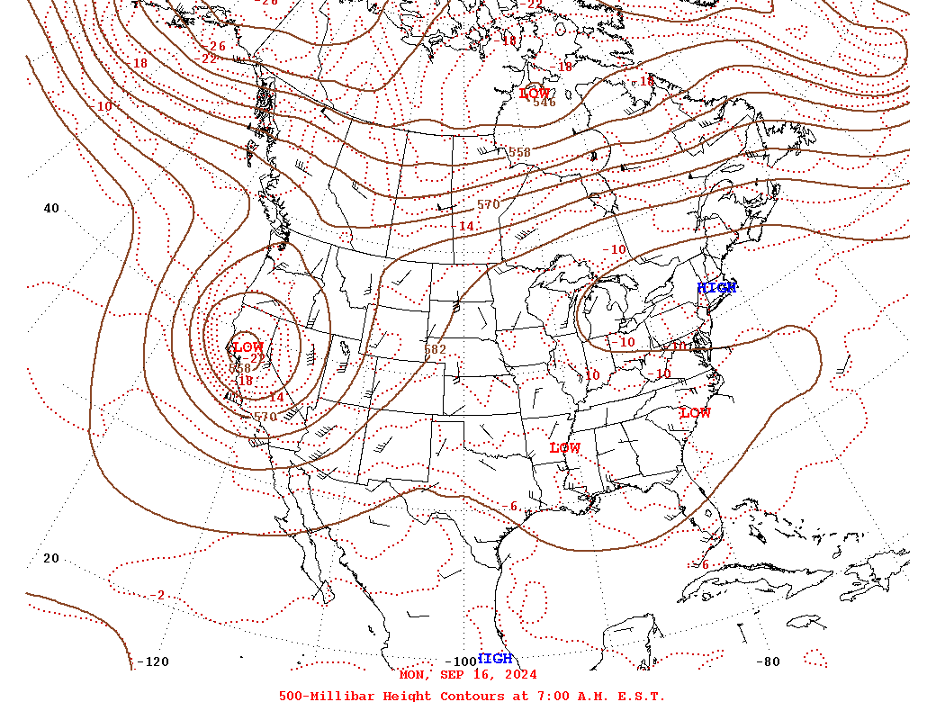

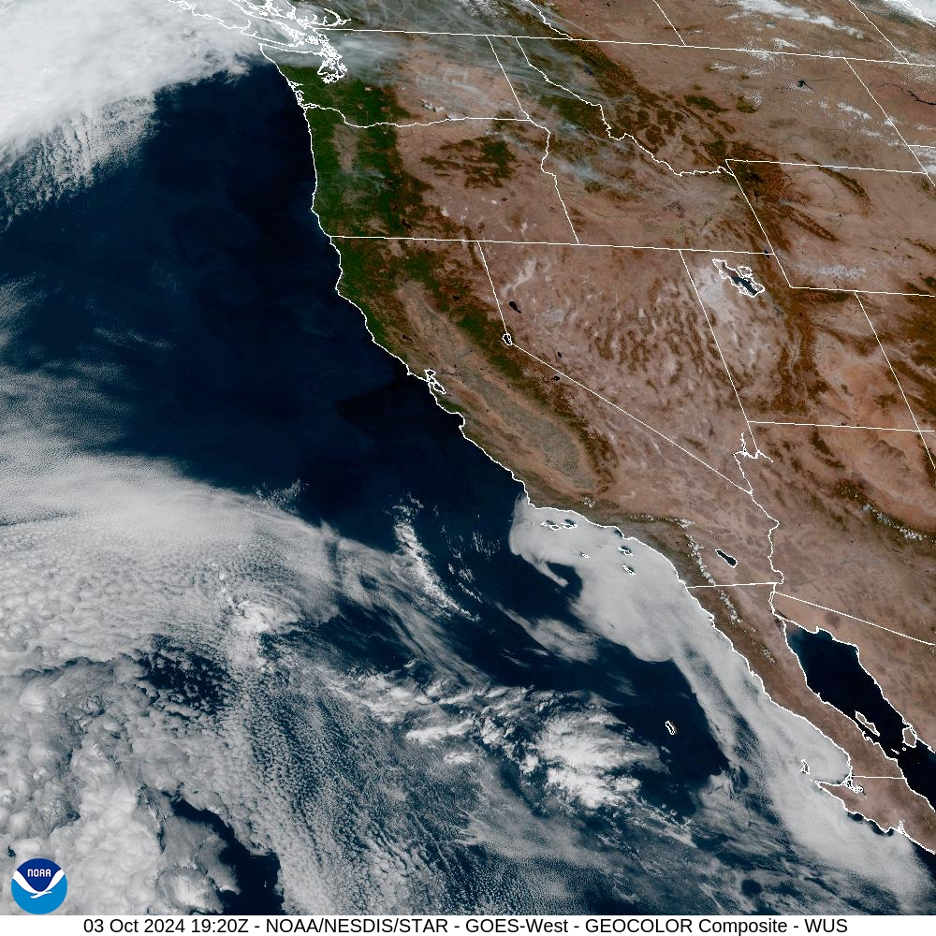

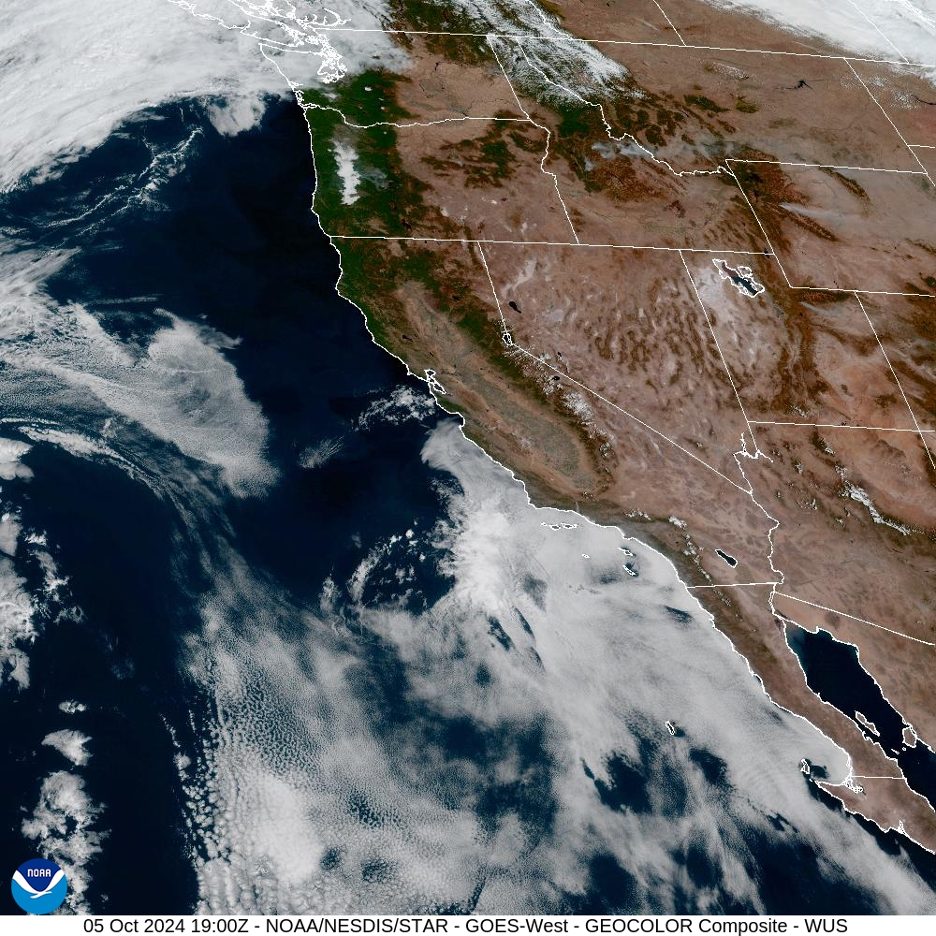

The first surprise was an early season Pacific Northwest storm that dragged a dry cold front down the coast in mid-September. High winds following that system churned up coastal currents, quickly dropping Golden State water temperatures by several degrees. For instance, Santa Monica Bay water temperatures that had just spiked near 72° F plummeted at least 7 degrees, down below 65° in just two days. Water temperatures wouldn’t recover, forcing an early end to my comfortable summer swims without a wetsuit. A premature Southern California coastal chill was suddenly noticeable in the daily sea breezes, which often ebbed below their dewpoints, causing the air to remain saturated for longer periods spanning several straight days. (Some NWS forecasters have postulated that the threshold water temperature, helping to determine whether or not summer marine layers are saturated with fog and low clouds as they drift onshore, is around 68°F.) Along the Southern California Bight, stubborn fog and low clouds condensed over the cold water and hugged the immediate coast into October as if May gray or June gloom conditions forgot to check the calendar, while the expected seasonal offshore wind trends were not strong enough to shove the shallow misty muck all the way out to sea.

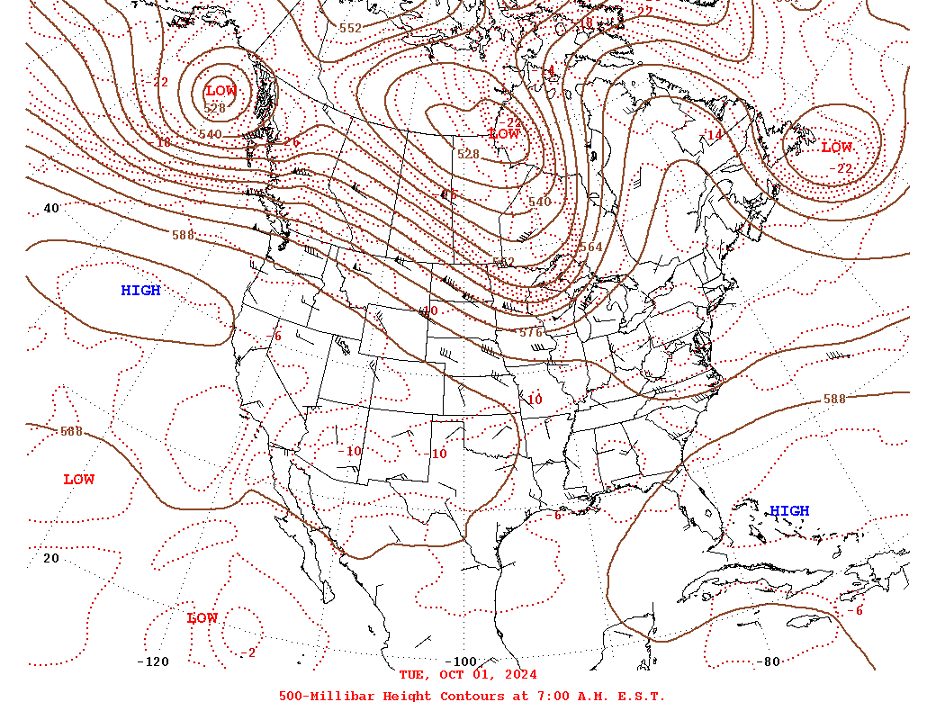

Just several miles inland, and throughout parts of Northern and Central California, it was a radically different weather story. Some of the strongest high-pressure domes on record for the dates anchored directly over the state and into other southwestern states. As the calendar flipped from September to October, a prolonged and dangerous heat wave intensified. Air columns were compressed and superheated to break numerous daily records until several inland stations recorded their all-time highest temperatures for the month of October. As is often the case in autumn, the offshore trends occasionally swept all the way to the beaches in parts of Northern and Central California. Intense heating of the brilliantly clear dry air pushed temperatures over 90° F in San Francisco and 100° F slightly farther inland, from Santa Rosa to San Jose. Exemplifying those rare warm San Franciscan nights, surrounding Bay Area hills recorded overnight low temperatures well over 80° F beneath the descending air columns. More high temperature records were broken in the Central Valley. Back down in Southern California, the stage was set with conditions that produced some of the most extreme temperature gradients (across such short distances) on the planet.

Epic Southern California Temperature Gradients

As high pressure strengthened directly overhead, numerous daily records (and some all-time October records) were also broken in Southern California’s deserts and inland valleys (see the list near the end of this story). Indio and Palm Springs made it to 117° F, their hottest temperatures ever recorded for October. On October 6, it got up to 116° in Indio, which is the hottest it’s ever been so late in the year anywhere in California. Exceptional high-desert temperatures repeatedly exceeded 100° F in early October and inland valleys were even hotter. Paso Robles hit 107° and Woodland Hills (in the western San Fernando Valley) topped out at 113° F. And in contrast to the annual cooler Great Basin High common to autumn, these hot high-pressure domes formed right overhead. So, instead of generating strong offshore winds typical of October, they compressed gentler breezes that couldn’t make it to the surface along the immediate Southern California coast.

This resulted in unseasonal temperature gradients that would have been remarkable even for June and July. For instance, on the afternoon of October 1, it was 67° F in Oceanside when it was 117° in Palm Springs, less than 70 straight line miles and a few mountain barriers inland. On October 2, when it was 71° F along PCH in Malibu, it was a sizzling 111° in Woodland Hills, less than 10 miles and a small mountain range away. Imagine such a temperature gradient of more than 4 degrees/mile! Folks who headed to the beach to escape record inland heat were astounded when they were met with a wall of shallow cold fog that drifted along the beaches and only several blocks inland during the day, and then crept only a few miles farther inland at night: June- and July-style heat waves (as featured in an earlier website story) trending into October. By late October, inland temperatures were mercifully moderating, though persistent high pressure continued to clamp a lid on the stubborn shallow marine layer that was attempting to creep in below it. By the time the Dodgers were beating the Yankees in the first two games of the World Series, a packed Dodger Stadium crowd had a clear view looking inland toward the warm mountains, while a distant hazy marine layer loomed toward the coast. It was the kind of perfect Southern California baseball weather that can make national audiences envious, another interesting topic in my California Sky Watcher book.

Though every heat wave has its own personality, these recent record busters followed a trend that has become all too familiar in California and the Southwest U.S.: while all weather stations are showing signs of warming, inland locations are heating up faster. This is likely due to the modifying effects of ocean breezes that dominate our coastal regions but don’t penetrate far enough inland, resulting in slower warming along the immediate coast and enhanced temperature gradients toward super-heated inland regions. And this leads us into Part Two of this heated discussion. If you are interested in what lurks behind all the wild weather whiplash and record temperature extremes that are threatening and remaking our Golden State, click on to Page Two of this story. You might first want to surf down the list (below) of some remarkably high temperatures recorded during our historic 2024 October heatwave and then see what weather patterns finally broke the heat spell.

Afternoon of Oct 1:

Oceanside: 67°F versus 117°F less than 70 miles east in Palm Springs (record for October).

Afternoon of Oct 2:

Topanga/Malibu coast: 71°F versus 111°F less than 10 miles inland in Woodland Hills (record).

Here are examples of early October, 2024 high temperatures (in F degrees) recorded at selected weather stations in California, with some comparisons to previous records:

- Campo: 105 degrees.

- Hanford: 100, breaking the prior record of 98.

- Idyllwild: 98, breaking the prior record of 93.

- Indio: 117, breaking the prior record of 111.

- Kentfield: 100, breaking the prior record of 97.

- Lake Cuyamaca: 94, breaking the prior record of 89.

- Lancaster: 103, breaking the prior record of 100.

- Madera, 100, breaking the prior record of 99.

- Palmdale Airport: 104, breaking the prior record of 100.

- Palm Springs: 117, highest ever for October (116 in 1980).

- Palomar Mountain: 93.

- Paso Robles Airport: 107, breaking the prior record of 106.

- San Jacinto: 106, breaking the prior record of 105.

- San Rafael: 105, breaking the prior record of 104.

- San Jose: 100, breaking the prior record of 97.

- Sandberg: 95, breaking the prior record of 92.

- Stockton Airport: 101.

- Woodland Hills: 113, breaking the prior record of 110.

Before clicking on to Page 2 to review climate change trends (from that National Weather Service workshop), you might check out the following weather patterns that finally broke through the high-pressure domes and heat waves as we made our way through October, 2024.

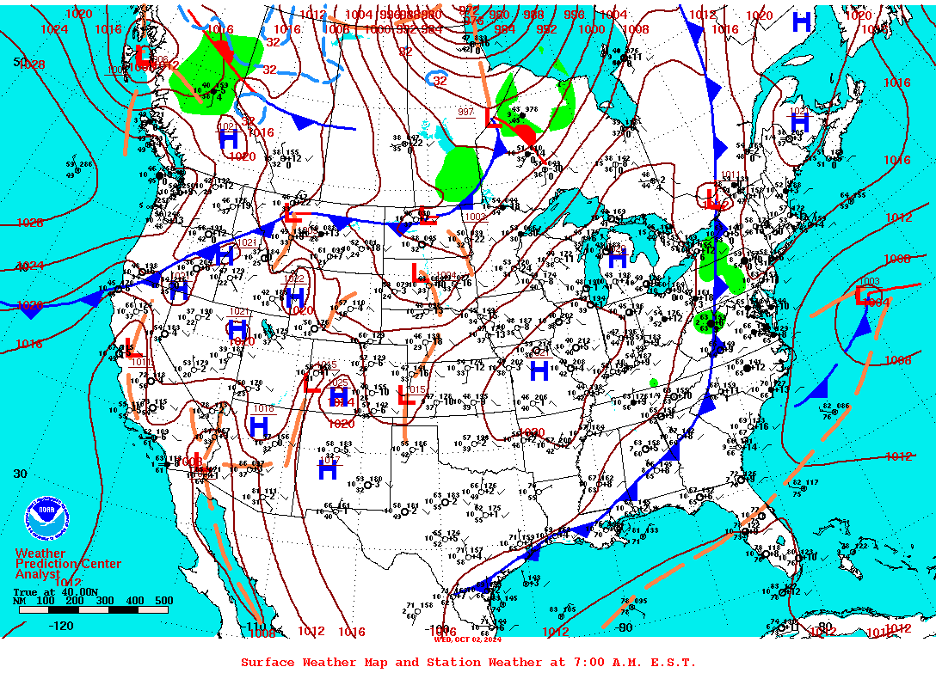

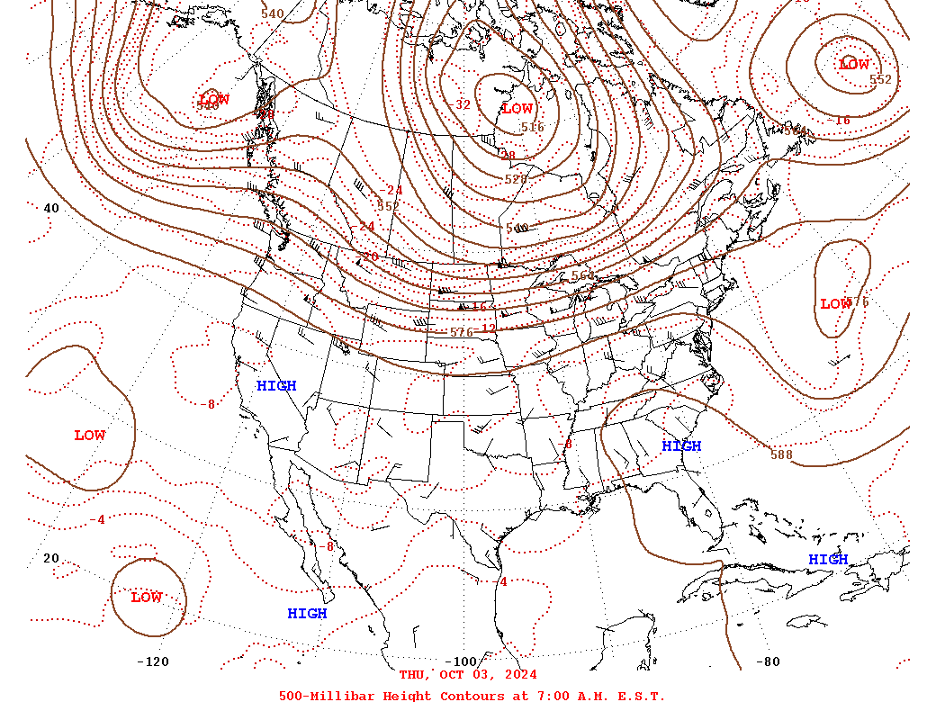

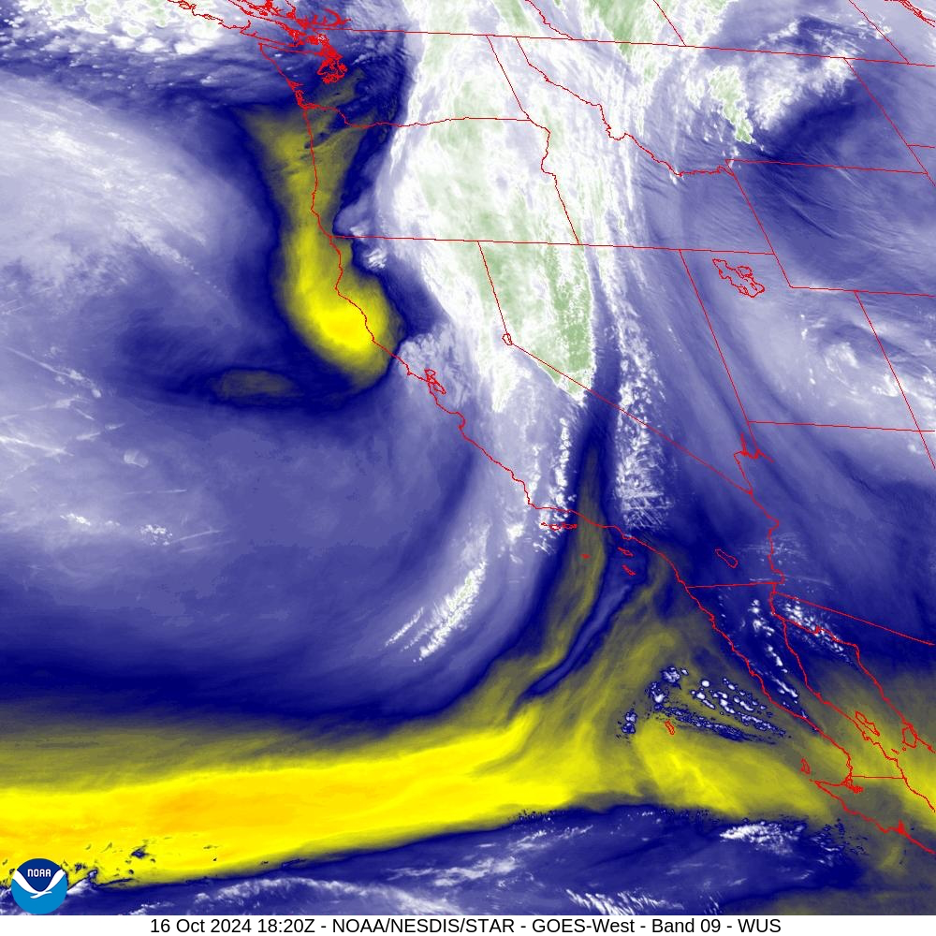

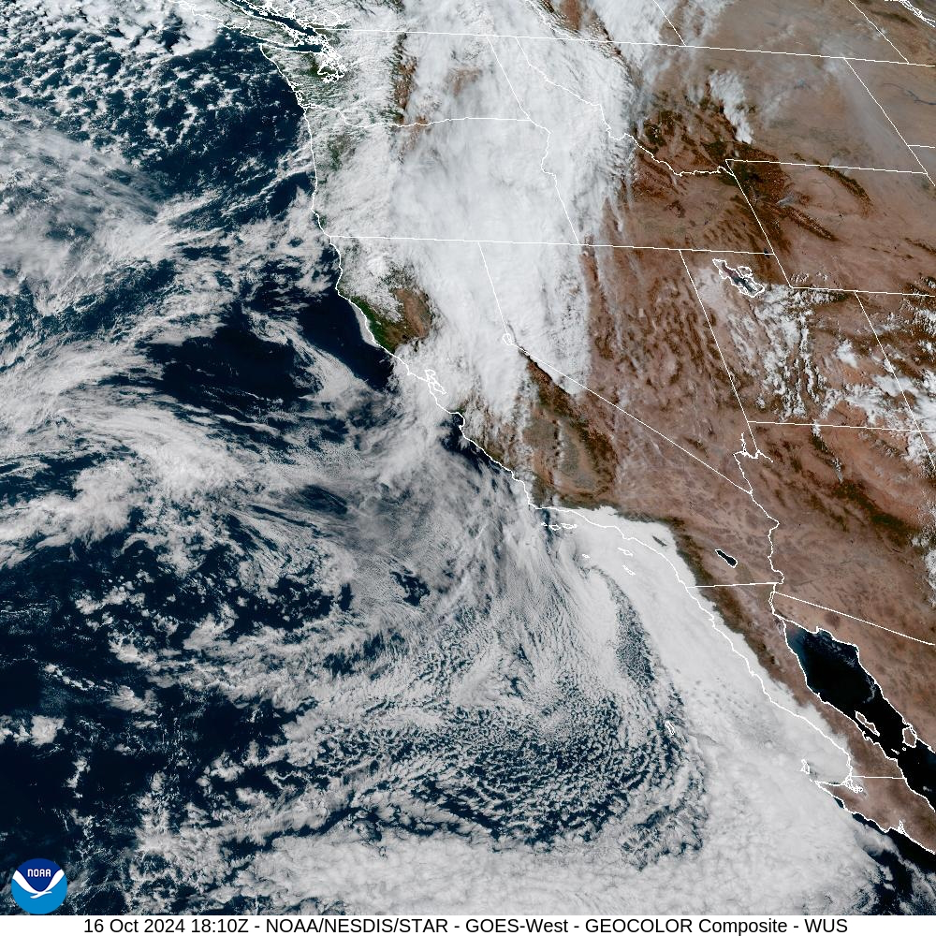

Breaking the Heat Wave

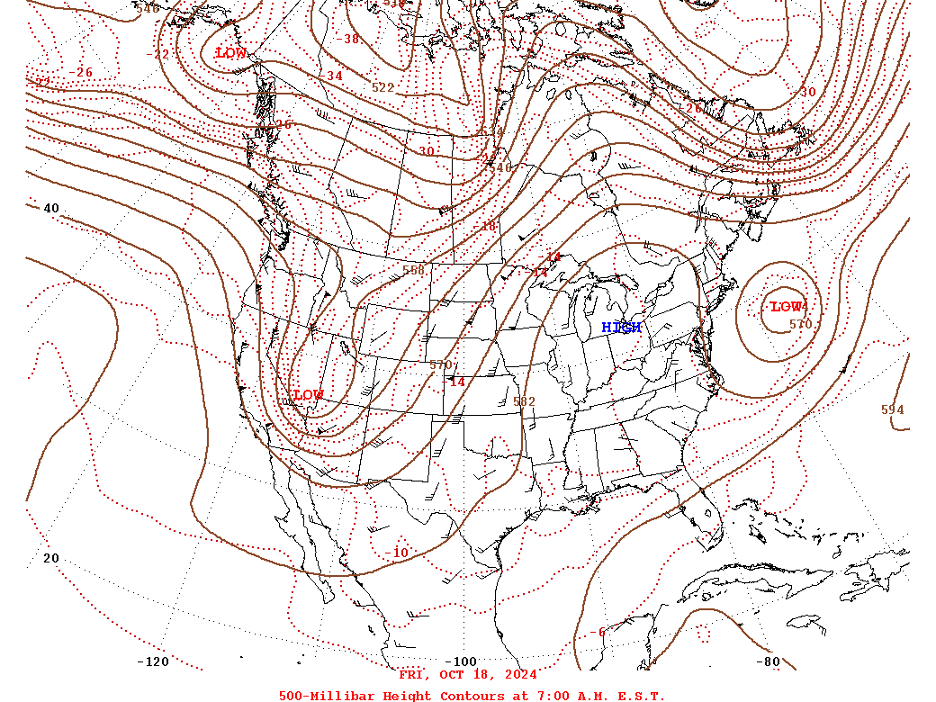

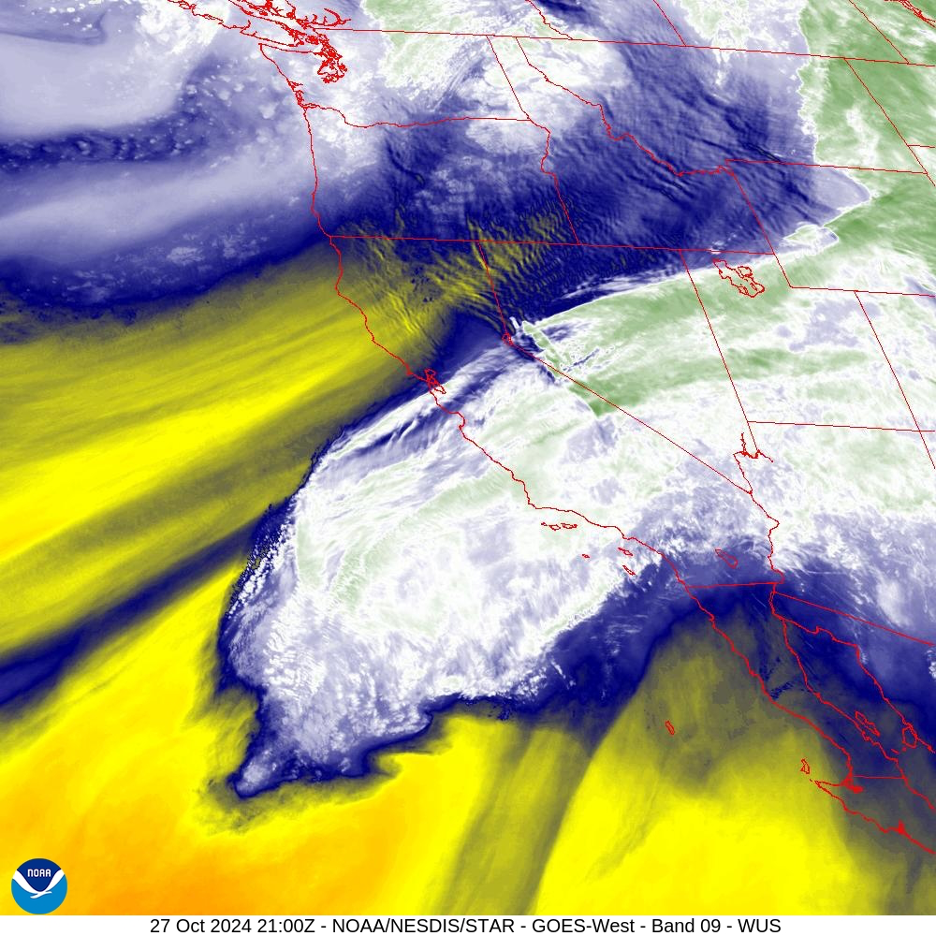

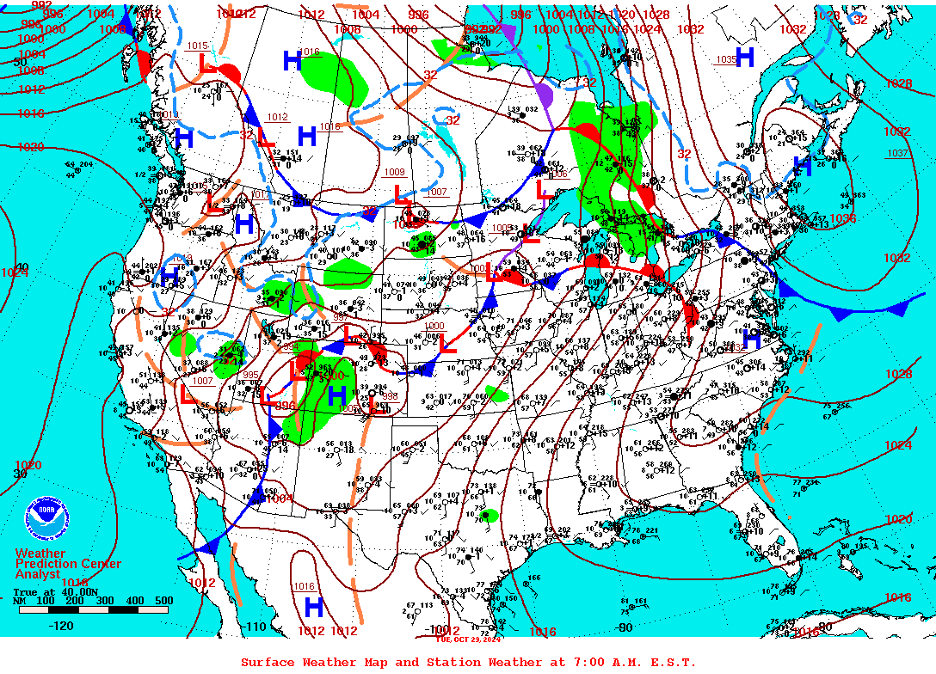

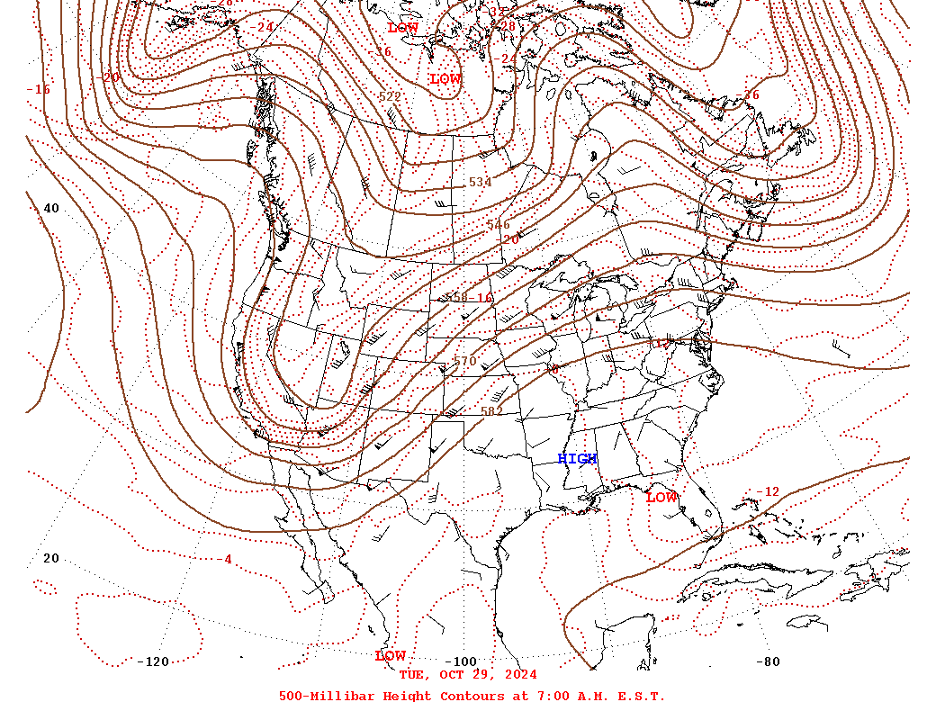

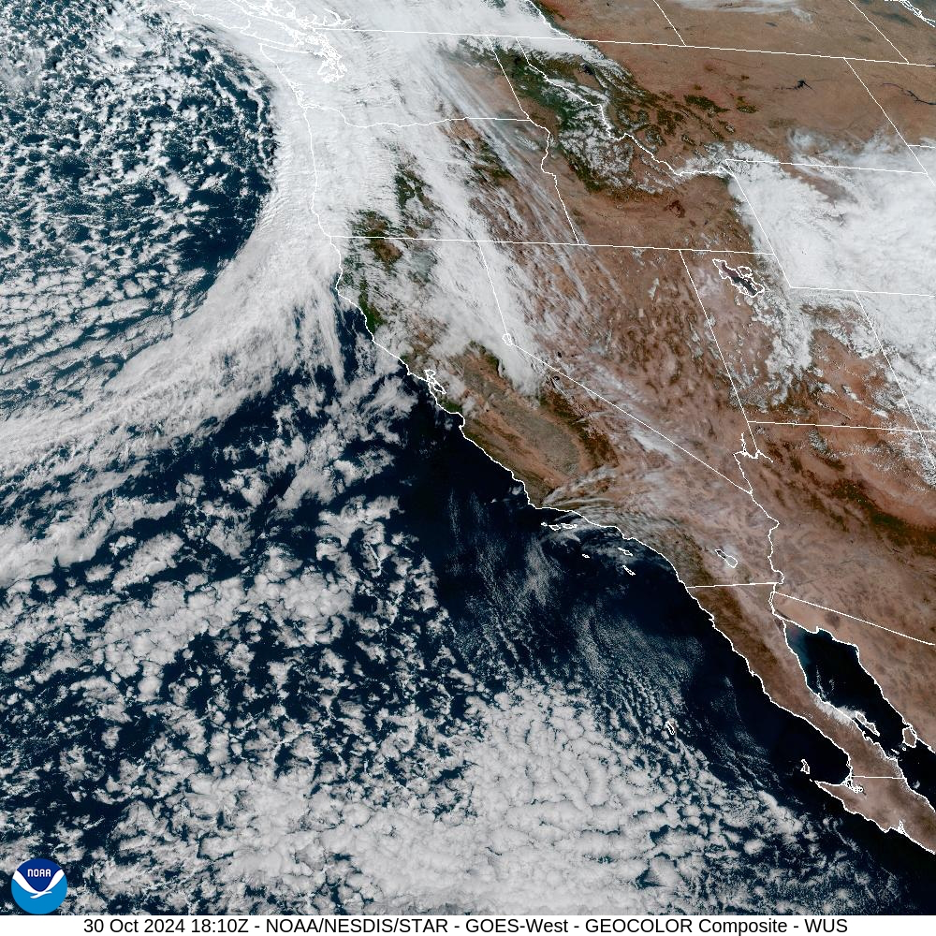

Even the most stubborn and historic weather patterns must come to an end, and so it was for the unprecedented summer that bled into October 2024. The following images illustrate how California weather finally shifted to what we might expect in autumn.

If you are interested in reviewing some of the trends (with help from a National Weather Service workshop) that might help to explain these autumn records, click on to Page 2 of this story. At the end, you will also find a long list of links that dive into climate change trends in California and how we are measuring and dealing with extreme heat events. You can start with the following image:

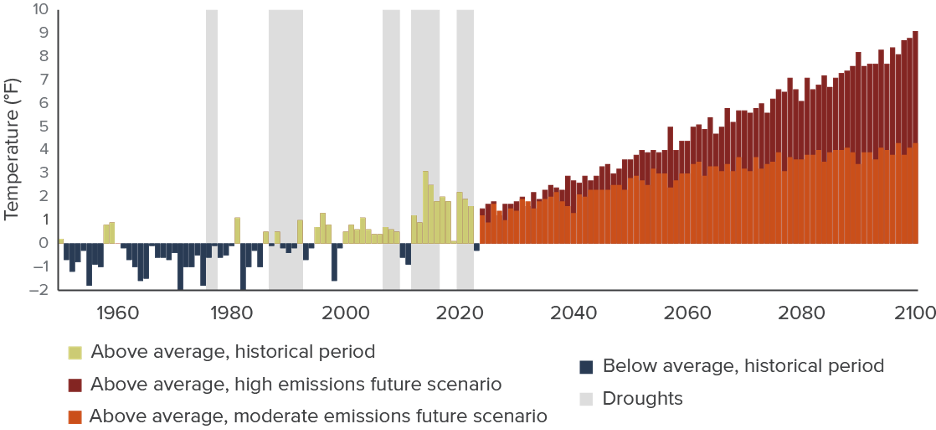

NOTES: Historical observed temperature data are shown for the period 1950–2023. Data derived from the output of downscaled GCMs (e.g., climate model data) are shown for the period 2024–2100. The moderate emissions scenario is RCP4.5 and the high emissions scenario is RCP8.5. These downscaled GCM data were originally published in California’s Fourth Climate Change Assessment as annual maximum and minimum temperature time series. For further details, see the source notes to this brief.

The image above shows historical and projected California temperature trends as shown in PPIC’s Priorities for California’s Water .

Click to Page 2 for Researching Heat Risks and Heat Wave Trends with the National Weather Service.

Excellent!! Good overview of heat waves and heat risks. Also enjoyed reading the synopsis of fall weather.