Part Two

Extreme Precipitation in a Climate of Change

California’s great megadrought marched through the first two decades of this century. It was finally broken by two consecutive years of record storms and floods. We have documented and analyzed these events and their impacts in previous stories on this website. That brings us up to this 2024-2025 bizarre bipolar season. We’ve got some explaining to do as meteorologists and climate scientists are following nature’s clues to better understand the weather whiplash chaos that rocks our state and our world.

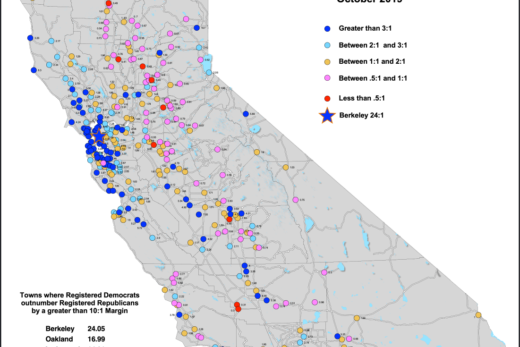

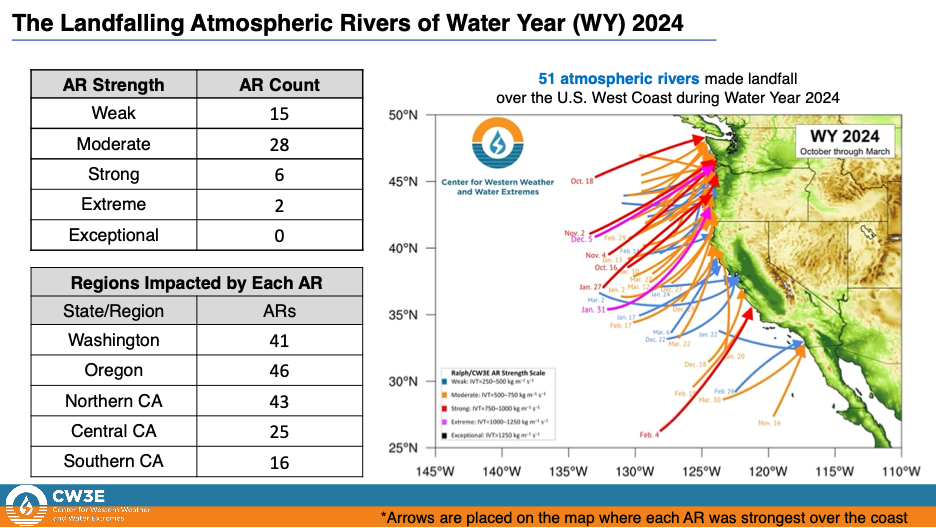

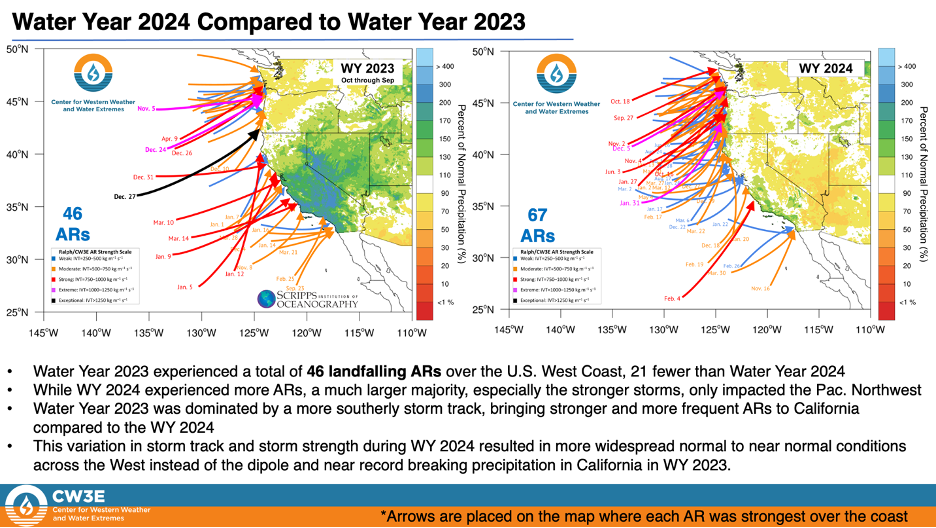

So, why does California experience the greatest precipitation variability compared to any other state? The annual seasonal droughts that help define our Mediterranean climates typically extend from May through September, sometimes without a drop of measurable precipitation. By contrast, California relies on the six-month cool period from November into April (and particularly our wettest months from December-March) for storms to deliver water to our thirsty ecosystems and water projects; much of that precipitation falls during only a few days when atmospheric rivers (ARs) transport copious amounts of moisture across the Pacific. Adding to this variability, the number of ARs impacting California can vary from only a few during one dry year to about two dozen the next.

“Anticipating and Planning for California Floods – Past and Future” was the theme for the California Extreme Precipitation Symposium I attended last July 2024 at UC Davis. It should be no surprise that several presentations summarized recent research about ARs, as we have on this webpage. That is also why Weatherwise Magazine is publishing my article about atmospheric rivers in their winter edition this year.

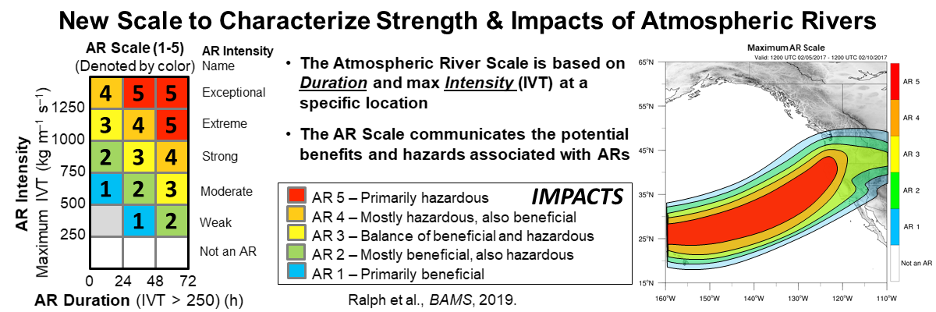

Meteorologist Marty Ralph (Scripps Institution of Oceanography) starred by summarizing his decades of AR research. He had been studying atmospheric rivers in the 1990s when Yong Zhu and Reginald Newell of MIT coined the term. Back then, we sometimes used ”Pineapple Express” to describe these meandering jets of moisture. But there are always a few of them flowing somewhere around the world (mostly between 30°-60° latitudes) and even ours don’t always come from near Hawaii.

I’ve been fortunate to experience numerous AR storm years and to appreciate how each develops its own personality. The floodwaters, storm surges, and towering waves generated by powerful ARs during the 1982-83 El Niño took some forecasters and officials by surprise, resulting in lives lost and billions of dollars in damage. I remember walking along our shoreline observing clumps of debris torn away and washed down from distant inland landscapes, which then mixed in the surf with flotsam from the Santa Monica Pier and other coastal structures that broke off and floated away. Such dramas would be repeated up and down the California coast during other severe AR events that followed, such as in the last couple of years in Santa Cruz. But lessons were learned and models improved so that the 1997-98 El Niño was anticipated months ahead of time. After consulting climate scientists (such as CalTech’s Bill Patzert), officials had time to prepare flood control and other infrastructure for the coming AR deluges. Countless lives and billions of dollars were saved. During the last two decades, we’ve learned how ENSO and other ocean-atmosphere interaction cycles + shifting pressure systems + ARs + climate change can conspire to make winter storms more volatile and difficult to predict. We’ve also learned how sudden weather whiplash can switch us to severe drought modes when storms are blocked, such as during the perilously dry start to this year’s La Niña rainy season in Southern California, where residents could only dream of rain.

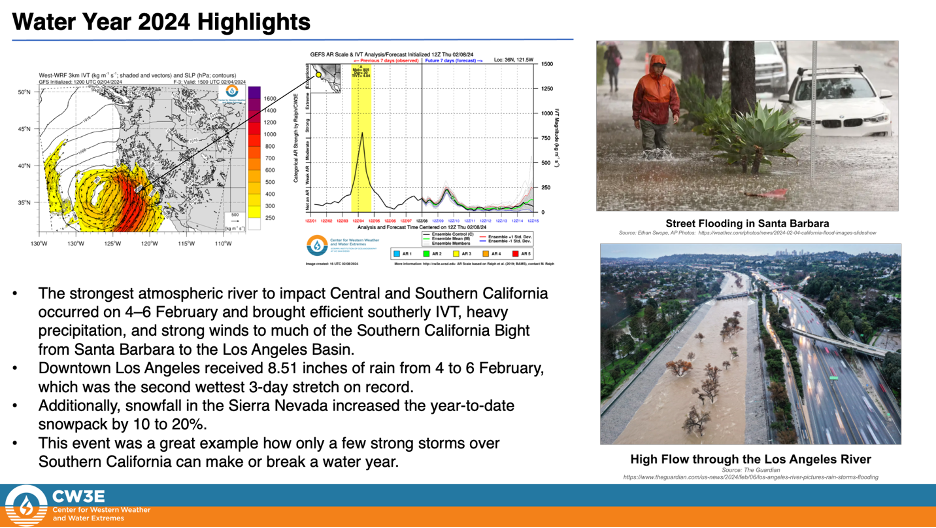

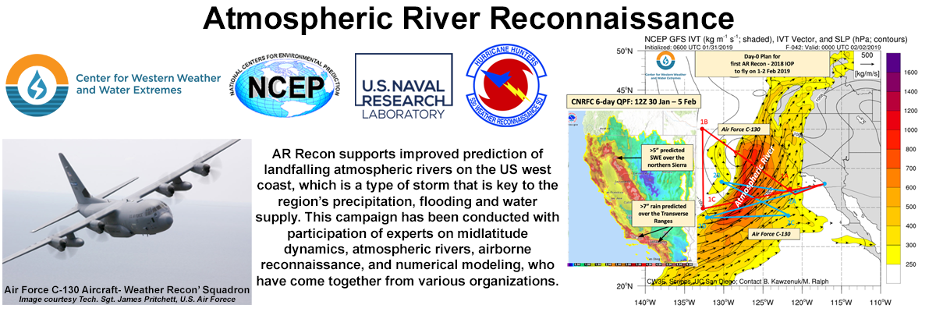

The Atmospheric River Reconnaissance Program is improving vital forecasts as ARs make landfall. It is led by the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) at Scripps as a partnership between scientists that include operational weather forecasters within several government agencies and universities. Researchers and forecasters are aided by AR flight reconnaissance missions and dedicated supercomputers. Check out their websites at: https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/ and https://cw3e.ucsd.edu/iwv-and-ivt-forecasts/

Back at the 2024 Extreme Precipitation Symposium, climate scientist Daniel Swain was among the many meteorologists, climatologists, hydrologists, engineers, and public officials attempting to explain why California is already the leader in interannual precipitation irregularity and hydrometeorological variability. But he and other scientists at the symposium also emphasized how climate change has increased the frequency and severity of anomalous weather patterns that include ARs. As example, just as severe droughts and dehydrating heat waves have become more common, a repeat of the epic floods of 1861-1862 are also becoming more likely in California. This is when up to 80-100” of rain were (and will eventually again be) squeezed out of a series of atmospheric rivers driven into our mountain slopes within a month. Check out the ARkStorm Scenario report published by a team of scientists who show how such megastorm flooding today would be even more catastrophic than our anticipated earthquake that is infamously known as “The Big One” on the San Andreas Fault system. You can understand why we’ve dedicated so many stories to these topics on this website and in my book. Check them out (and that AR article that will soon appear in Weatherwise Magazine) when you get a chance.

Meanwhile, numerous agencies in watersheds across the west are struggling to adjust to these climate change challenges with their own water storage and flood control projects. Central Valley flood management is now on par with New Orleans and the lower Mississippi because major cities, the nation’s largest water projects, and the most productive agricultural valley in the country are all threatened. Scientists and officials are scrambling to lessen the risks with their Central Valley Flood Protection Plan. And even as I write this, coastal slopes and valleys of Southern California are experiencing a series of powerful dry Santa Ana wind events and historic firestorms. They are blowing across slopes and valleys that have received less than a quarter inch of rain since spring. Here we are, headed into mid-January and the middle of our rainy season, as catastrophic wildfires ravage our parched landscapes, imagining how just one atmospheric river could save us from further destruction.

This is an early winter scene near Bear Valley Springs, a gated community west of Tehachapi. Late in 2024, these Kern County landscapes were situated between the big storms and ARs sweeping through Northern California and record drought to the south. On this day, a lone dormant oak stood in front of high cirrus clouds teasing to suggest one of those northern storms might soon visit. By contrast, unrelenting fair-weather high pressure capped the stable incessant valley (tule) fog and haze that commonly settles in the San Joaquin Valley through winter. Photo by Charles Hood.

For those looking for more atmospheric river details, surf through the following images from the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes.

Still want more? Here are a few related links:

Here is a recent article suggesting how climate change might energize atmospheric rivers as they head toward the West Coast. Thanks to Bill Patzert.

Some Reaction to our Water Woes

The documentary Dry Times, made by Anurag Kumar and Alex Gregory, has, unfortunately, become more relevant as it captured California’s recurring predicaments during the megadrought that spanned more than two decades: Given recent events, this has become a haunting trailer. The Movie

THE END