It’s been revered, worshiped, and feared for centuries, thoroughly researched by stellar scientists, and altering landscapes across our state and around our world more than you might think. Because lightning accentuates many of the weather patterns covered in our previous website stories (such as our sporadic summer monsoon), we’re giving it more respect and attention here. This electrifying story was inspired by Oscar Rodriquez, AKA Lonewolf Thunderhorse. We will cap it with a haboob postscript that includes stunning videos.

Does Lightning Really Need an Introduction?

Lightning is anything but boring: volatile, explosive, cryptic, enigmatic, mystical, uncanny, fickle, erratic … pick your attribute. The National Severe Storms Laboratory has described lightning as a “capricious, random, stochastic and unpredictable event”. For thousands of years, people have marveled at these dazzling light shows that can be seen more than 100 miles away and their bombastic explosions of thunder that are propagated about a mile every 5 seconds and can be heard rumbling for more than 10 miles from the firebolt. Lightning has ignited fires that have incinerated ancient redwood forests and transformed nearly every other California plant community. If you explore the science behind lightning, you quickly understand how such shocking theatrics connect us and everything on our planet, always reminding us who’s boss.

Energy from the sun evaporates moisture, which rises and condenses into clouds, which releases latent heat, which fuels boiling thunderstorms, which helps to generate the awesome electric potential that sparks lightning. Typically, the tops of cumulonimbus clouds become positively charged, while negative charges accumulate on their bottoms. Though initial energy sources can also come from wildfires and volcanic eruptions, the most common trick is to get moist air to rise as fast as possible: the wettest and most unstable air masses generate the most severe thunderstorms with frequent lightning. Their narrow sparks of about 300 million volts or more can heat the air to 54,000°F (30,000°C), causing the explosive expansion of billions of air molecules and the crashing shock wave sound we know as thunder. As many as 2,000 thunderstorms are active on Earth at any time, totaling more than 14 million storms each year, generating about 6,000 lightning strikes each minute, and California experiences its share of these spectacles. Most lightning branches through the clouds, but when a cloud-to-ground bolt strikes too close, you will never forget it. I’ve seen trees splintered into shards and sandy soils melted and fused into glass-like branches (fulgurites) that trace the path of electric currents as they radiated out from where the bolts were first grounded.

It is true that tall objects, higher geographic features, and good conductors are most vulnerable, but erratic lightning can strike anywhere. Suffer a direct hit by a bolt, and you’re toast; but nearby strikes and distributary forks burn and electrocute more than 200 people in the US each year. Your chances of being struck are about 1/15,000 during your lifetime. And despite what you’ve heard, lightning originates in a cumulonimbus cloud and usually can travel only a few miles. (The record 500+ mile megaflash along a line of storms from Texas to Kansas City in 2017 is a very rare world-record exception. This AMS article is for you if you can’t get enough of the lightning science behind that shocking event.) Now that I’ve piqued your interest, I won’t repeat all the lightning details that are readily accessible elsewhere; you will find excellent links near the end of the next section of this story to guide you through the science, along with links to related stories on this website and narratives in my recent California Sky Watcher publication.

And Now, Introducing the Star of This Extreme Science Show

It’s time to return to the inspiration for this story: certified naturalist Oscar Rodriquez. Oscar writes how his creative name, Lonewolf Thunderhorse, “comes from my love of storms and wild nature—it captures the sense of being both solitary and deeply connected to the raw power of the earth and sky.” Perhaps that is why he happened to be in the right place at the right time, at The Commons in Chico, California on Tuesday, Aug. 26, 2025, around 9:30 p.m. Compared to previous years, California had experienced a relatively cool summer. But by late August, the weather patterns turned hot and turbulent. You can review the how-and-why details that led to such weather reversals (and their consequences) after Oscar shares his images and shocking storm experiences in his own words, from the Chico Commons.

The two shows started at 8 p.m. with the Wheeland Brothers, followed by Joe Samba. The music had the place buzzing when the storm moved in, making the night unforgettable. That day’s temperatures had climbed into the low 90s before cooling to the mid-70s after sunset. The heat mixed with lingering humidity set the stage for instability. Sure enough, a fast-moving storm built over the Sierra Nevada to the east and swept into the Sacramento Valley. By the time it hit Chico, it was alive with lightning—sharp forks that lit up the sky and turned the outdoor show into a dramatic showdown between music and nature. For the crowd, it was both exhilarating and dangerous—nature reminding us who was headliner.

Shot on my Samsung Galaxy S22, using Super Slow-Mo mode.

The fuzziness comes from the focus slipping in low light; unfortunately, I don’t have a clearer version.

The effect that looks like “linked snapshots” is just how Super Slow-Mo stitches frames together.

The round white dot you noticed on a lightning fork is an overexposure artifact—when the sensor is overwhelmed by lightning’s intensity, it creates that ghostly orb. Nothing was added or altered; the video is straight out of the camera.

Thanks again to my friend and former student Oscar Rodriguez for sharing his fortunate drama; he describes himself as a naturalist and “photographer and storm-chaser at heart”, which feels true to both the image and the story behind it.

The next section of this story follows those explosive air masses that invaded from the tropics into California during the end of our summer, 2025. When you have finished with our last sections, return here to these links for more lightning and thunderstorm science and details.

These sources help explain the science behind thunderstorms and the lightning they generate:

NOAA’s How Lightning is Created

The following links take you to previous stories on our website that feature thunderstorms:

Here are a few of our previous website stories following monsoon weather patterns:

Here are some of our previous stories highlighting lightning and wildfires:

Making Sense of the Monsoon Madness that Broke Summer’s Mildness

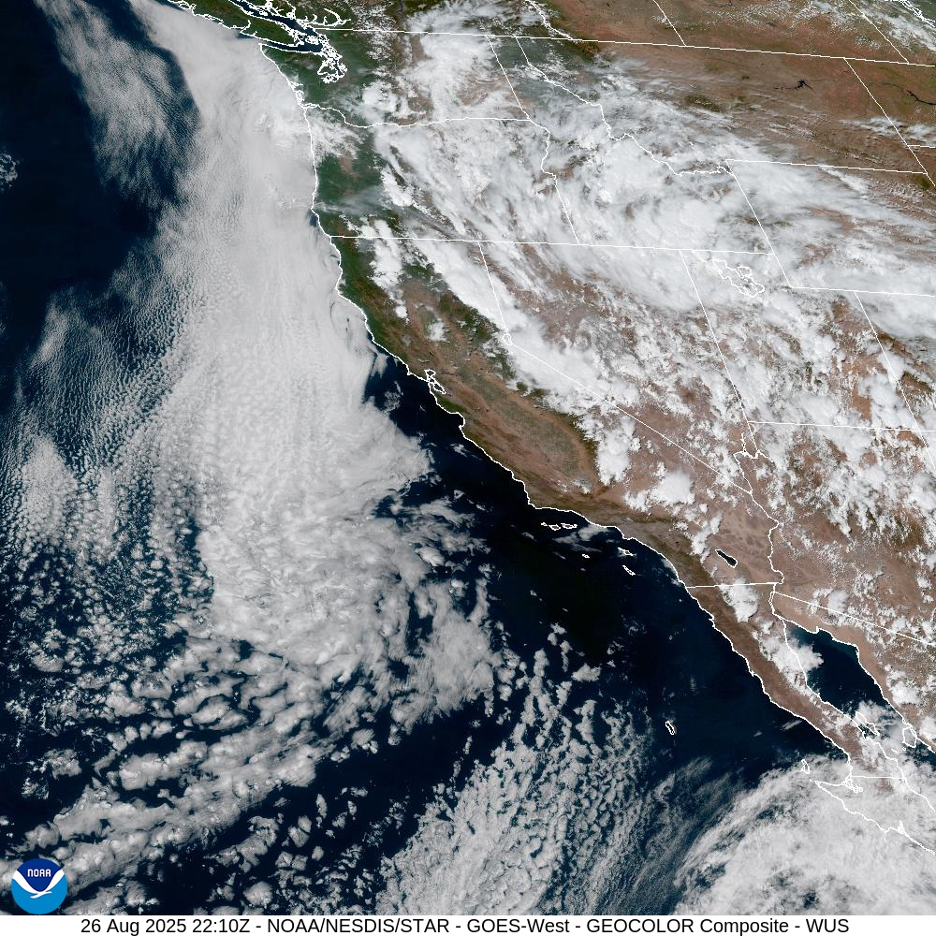

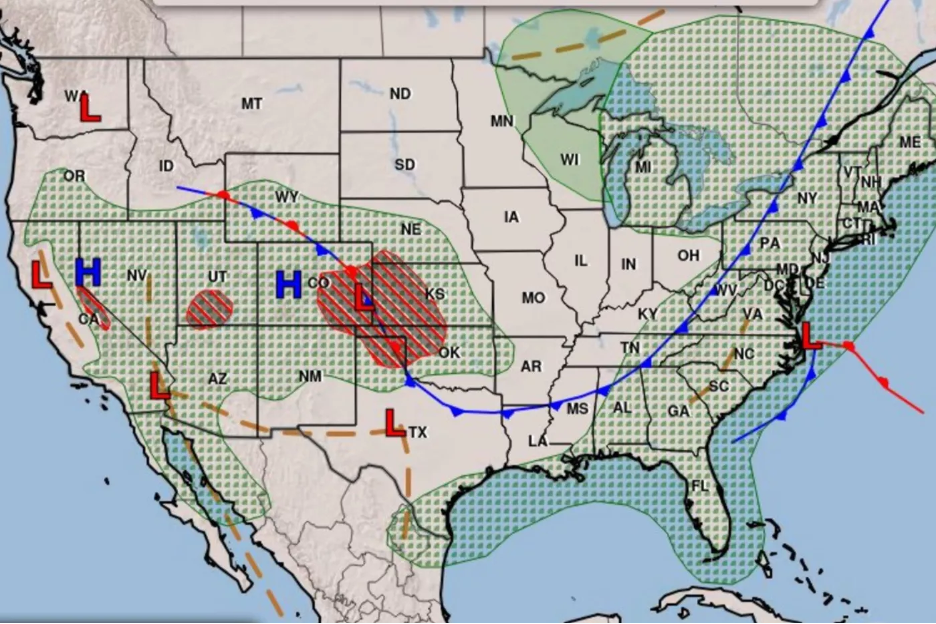

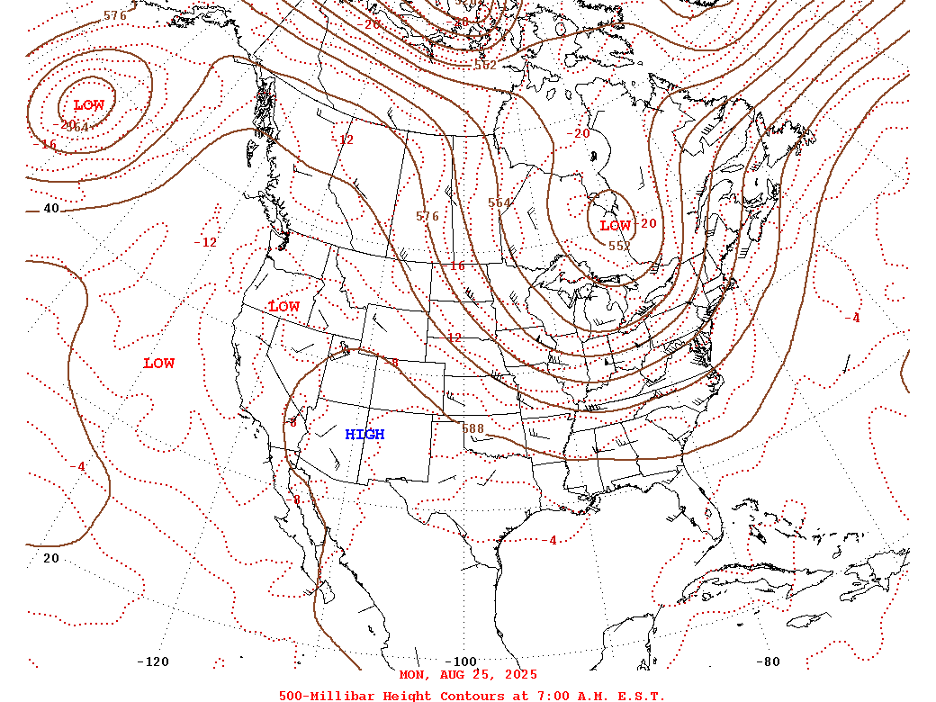

In contrast to recent summers, most of California experienced a cooler-than-average high-sun season into August, 2025. Persistent troughs of weak low pressure anchored along the west coast and spread cool sea breezes farther inland than usual; relatively dry, stable winds from the west pushed summer’s moist, muggy monsoon air masses far to the east or into Mexico. (Check out our previous website stories—listed above—about the Southwest/North American Monsoon.) But circulation patterns finally changed by mid-to-late-August, 2025, as summer’s familiar Four Corners High expanded over the desert southwest. Temperatures soared across the state, winds turned around the high pressure and swept summer storms into California from the southeast. Typical monsoon storms invaded inland California from Mexico and other southwest states until the steamy air masses were eventually blocked by our major mountain ranges; as is usually the case with our summer monsoon, folks west of the mountains (in cismontane California) could only look toward inland regions (transmontane California) to see distant towering cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds (AKA thunderheads).

The late arrival of heat and moisture glided north across the deserts, into the Basin and Range, and up along the spine of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, all the way into Oregon. Some storms brought beneficial rain to briefly interrupt summer’s drought, while other local storms generated that dreaded one-two-three punch so familiar with summer monsoon patterns: fierce dust storms (addressed in the Postscript of this story), dry lightning, and flash floods (see recent stories on our website). The heat and moisture brought instability and National Weather Service flash flood watches, which evolved locally to warnings across several states, into California. More than an inch of rain fell in an hour on desert locations from Yuma (on the AZ/CA/MX) border) into the Imperial Valley, nearly half their average annual total; the unstable moisture continued drifting north with steering winds, along and east of the Sierra Nevada spine and into northern Nevada.

Certain flight routes toward and out of LAX were briefly interrupted as jets couldn’t navigate around the big inland storms on Monday, August 28. Thousands of lightning strikes and up to 2 inches of rain in Sierra Nevada downpours (locally over 4 inches in Yosemite high country) generated sudden mudflows. Brief waterfalls were recorded over unlikely rock formations that included Lembert Dome above Tuolumne Meadows. In one week starting on August 22nd, California reported more than 74,000 lightning strikes. The flashes that danced over Chico (shared by Oscar in this story) came from one of these thunderstorms that spilled out of the Sierra Nevada and drifted over the Sacramento Valley.

Some of the storms delivered beneficial precipitation; others generated dangerous dry lightning that ignited more than 200 wildfires from the Sierra Nevada on up through the Klamath Mountains. Descriptive names were assigned to the big blazes, such as the Blue Fire and the SKU Late August Lightning Complex. But the Garnet Fire Complex stood out as it raged through Sierra National Forest east of Fresno and even threatened and burned below an ancient stand of giant sequoias. This article and video shows how the McKinley Grove was saved. Smoke from the Garnet Fire cut visibilities and spoiled air quality more than 100 miles away, depending on the wind currents, and it was still visible on satellite imagery into mid-September.

The late August storm surge from the south even interrupted opening days at Burning Man when the spotty weather chaos barged across the Basin and Range to points north. This annual celebration of the bizarre (expecting nearly 70,000 people) was first disrupted by dust storms; thunderstorms followed with heavy rain and dangerous lightning across the exposed Black Rock Desert. Roads turning into the event were blocked and revelers who made it that far had long waits at closed entries as sudden downpours made thickening, gooey mud impassable and threatened visitors with electrocution. Severe thunderstorm warnings were issued again for the region (northern Washoe County) on Wednesday, August 26. During that last week of August, 2025, Black Rock lived up to its harsh high desert weather reputation, with temperatures ranging from the 90s during the hottest days to the 40s during the coldest nights, punctuated by fierce winds, dust storms, driving rainstorms, and wild variations in humidity ranging from the teens to over 90%.

Across much of the American West, the relatively mild 2025 summer that started with a whimper was going out with a bang. Lonewolf Thunderhorse (featured earlier in this story) was lucky to capture a brief example of rare dramas orchestrated by nature when the western edge of summer’s Southwest Monsoon slops off the mountains and into California’s more densely populated inland valleys.

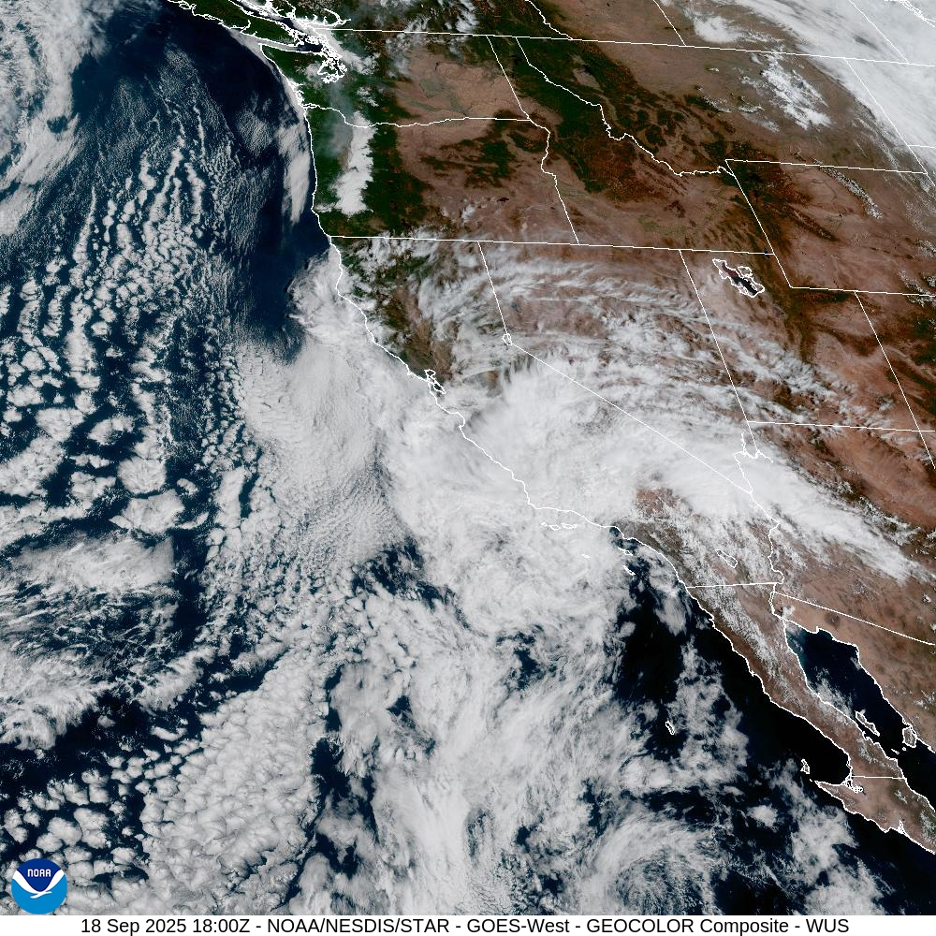

Once the monsoon door was finally open in California, the on-and-off muggy thunderstorm drama acted out through mid-September. Steamy surges were augmented when the remains of Tropical Storm Mario were pulled up from the Baja coast on September 17, spreading rare storms into the coastal hills and plains. A few mountain locations received record rainfall (for specific dates) that totaled up to 4 inches, generating deadly and destructive flash floods and debris flows that cascaded down the mountains and raced through desert washes.

A Postscript Celebrating Haboob Science

From northern Mexico and throughout the Desert Southwest, no discussion of summer thunderstorms is complete without acknowledging how they can generate some of the most bizarre weather events on Earth: haboobs. You don’t want to miss the breathtaking other-worldly haboob videos and the explanations that follow.

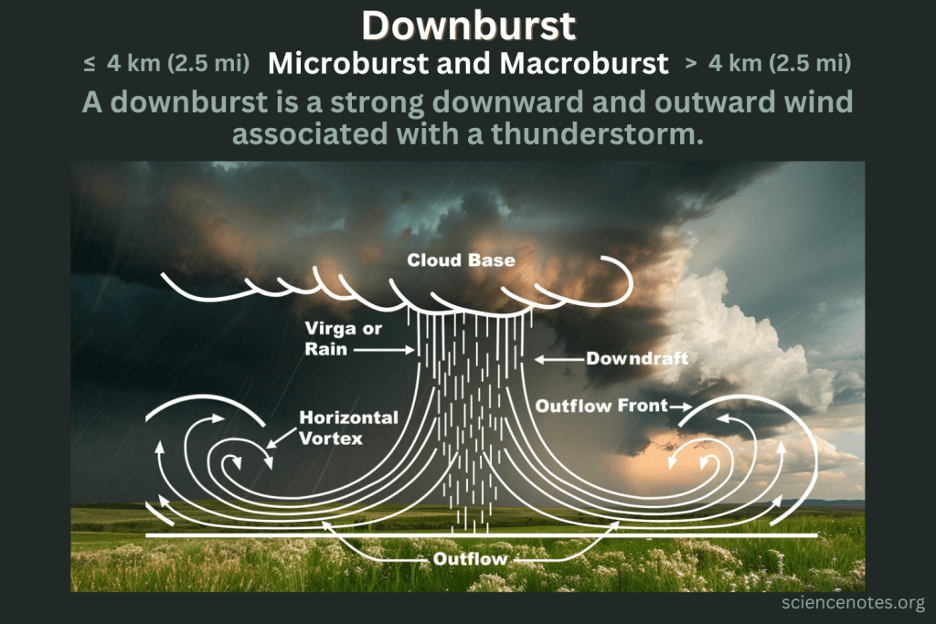

It is important to recognize that all haboobs are dust storms but not all dust storms are haboobs. Haboobs may form when violent downdrafts fall out of thunderstorms. As these cold downbursts approach the ground, they become powerful outflow winds that often push ahead of the storms for many miles. Should you be engulfed by the blinding, choking wall of apocalyptic dust, remember the National Weather Service Slogan often echoed by transportation departments: Pull Aside, Stay Alive.

Here are some haboob videos and scientific explanations. (Please excuse any annoying advertisements in some of these videos: they’re not ours, but are imbedded within the links):

This unforgettable haboob video was filmed as the erratic monsoon surged through Arizona and spread toward California, one day before Oscar Rodriguez captured his Chico lightning in our story.

Another successful storm chaser shares her unforgettable haboob experience.

Here is video of the dust storm that ravaged Burning Man, 2025.

Various videos from Arizona and Burning Man as the same monsoon surged north.

Dust storm and haboob science explained:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=THSm-I790H0

https://dust.swclimatehub.info/2.3

https://www.noaa.gov/stories/haboobs-phenomena-with-unusual-name-is-no-joke

https://research.noaa.gov/how-deadly-are-dust-storms

More haboob science:

https://www.earthdate.org/episodes/dangerous-haboobs

A simpler haboob demonstration for the younger at heart:

Radar Characteristics of Dust Storms:

https://www.weather.gov/media/psr/Dust/2020/1_Rogers_Dust_Storm_Presentation_DustWorkshop2020.pdf

As autumn closes in, leaving another summer to fade away in our rearview mirrors, I am reminded of Bob Seger’s haunting lyrics that seem appropriate to end this stormy story:

I woke last night to the sound of thunder

How far off I sat and wondered …