Whether Californians have learned to love or hate them, embrace, or reject them, cars have dominated California lives and livelihoods for more than a century. They’ve shaped our state’s cultures and human (and some natural) landscapes in ways that we too often take for granted. This story recalls how we celebrated our car culture until it impacted nearly every facet of our lives, from the very air we breathe to the ground we walk on to the microclimates we sense, and how some Californians have more recently rejected the “you can’t get there from here without a car culture” to reimagine life and landscapes beyond cars.

Just more than a century ago, the typical California commute or road trip around our growing cities and outposts was by foot, streetcar, or cable car, except for those who could afford a horse and buggy or carriage. Longer cross-country trips required wagons, stages, or trains. Bicycles were also pedaled into early urban scenes, with thousands of bicyclists organizing into bicycle clubs and demanding better roads for smoother bike rides. Our fledgling California settlements and wannabe cities grew into the 20th century without widely-paved roads and parking lots to accommodate cars.

Revolutionary “horseless motor carriages” began rolling across the Golden State in the early 1900s. By 1905, there were already more than 6,000 vehicles (including motorcycles and trucks) bumbling through city streets and breaking down and getting lost and stuck on treacherous dirt roads to nowhere across the state. By 1906, the Auto Club was erecting directional road signs along crushed rock surfaces covered with oil and less-navigable dirt roads to serve those who were wealthy enough to afford their own vehicles. Auto Club members were issued ever-changing and improving road maps.

After Ford rolled out the Model T in 1908, cars became more affordable for average families (and much less expensive than the shorter-range electric cars that were already navigating city streets) and the California car culture was off to the races. By the time the $18 million State Highway Act was passed in 1910, funding was far too paltry to build the roads and other car infrastructures that the public demanded in nearly every town, city, and county. Still, the bonds funded groundbreaking and paving designed to start a continuous system of roads built to connect cities and other key points from north to south (including the birth of what we now call Hwy 101).

As the number of vehicles multiplied, there were plenty of critics. They noted the clouds of smoke belched out from unsafe vehicles that were running over defenseless pedestrians and crashing into one another, resulting in appalling rates of injury and death. But an unstoppable wave of car culture momentum took control and our relationships with cars eventually became as complicated as the people who have driven and interacted with them and the astounding varieties of automobile makes and models that have come and gone over the years.

Into the early 20th Century, advancing streetcar tracks and technologies led to more efficient electric railways in our cities, often championed by real estate speculators who profited from increasingly dependable public transportation systems connecting to their new developments. Families with the financial resources were encouraged to move farther away from city centers to find their California Dreams on bigger lots within sprawling suburbs. Volumes have been written about how these early public transportation systems, ironically, set the geographic stage and paved the way for the freeways that would replace them.

The Arroyo Seco Parkway (later renamed the Pasadena Freeway) was completed in 1940 as the state’s (and arguably the nation’s) first freeway, connecting downtown LA to Pasadena suburbs. This was just a prelude to the pavement that was increasingly spreading and thoroughly covering and sealing the ground throughout cityscapes and suburbs and then extending in long and wide paths that radiated out to more remote coastal, mountain, and desert terrains. Following WWII, mass migrations into the state and out of our inner cities (commonly referred to as “white flight”) plopped millions of mostly middle-class families into outlying suburbs. These more distant developments were financed by bread winners encouraged by the accessibility and reliability of new free-flowing highways and freeways that quickly and conveniently linked commuters to urban centers.

Those with the resources evacuated the inner cities and took their wealth with them, leaving behind those without the means. Exacerbating the segregation and inequalities, freeways and other car-culture connections to the suburbs were often built through older neighborhoods with the least political and economic power to stop them. Bifurcated working-class communities from the Bay Area to Southern California looked on as people drove through and passed by their neighborhoods to their jobs in the city in the morning and then carried their earnings out to spend in the suburbs every evening and throughout most weekends. By the mid-1900s, LA’s Bunker Hill (which once served as home to the wealthy business class) became another symbol for the new urban California. The old Victorian homes were abandoned and then razed and replaced by sleek steel and glass skyscrapers to serve as office spaces for the growing number of commuters from the suburbs. The car-culture wave impacted every California city, but LA became the poster child. Automobile worship was first tempered and then ridiculed by some as a series of seemingly insurmountable and disturbing problems developed. Stand-out San Francisco fared better and even thrived at times by offering a denser, more cosmopolitan urban experience with all the exciting, cutting-edge cultural attractions and innovations (and convenient public transportation systems) that go with it. Most other California urban centers weren’t so lucky.

Little Selby (your author) was born into this California that was growing and changing faster than anyone could grasp. Our working-class outpost on the western edge of Santa Ana was quickly surrounded by a population and economy that seemed to take off with unimaginable changes in some places while other communities suffered from abandonment. Open fields that once supported orchards and truck crops grew cookie-cutter housing tracks attracting middle-class newcomer commuters. We watched new highways and freeways blaze their way through what remained of partially-open thoroughfares or reach farther by using eminent domain to scrape away older properties and neighborhoods that got in the way, new routes erected to support millions of neophyte commuters in their single-occupancy vehicles. We didn’t realize it then, but the growth and change was wild and unprecedented.

The times were exhilarating and exciting to some winners and participants, but troubling and destructive to some perceived losers who loathed a landscape and car culture with no sense of place or permanence. And these changes required wider roads, parking, and other paved spaces that dominated an infrastructure where cars were king. You know the old Joni Mitchell line about paving paradise and putting up a parking lot? Or how about Tom Petty’s editorial regarding life in Reseda, which more correctly referred to nearby parts of the San Fernando Valley: “There’s a freeway runnin’ through the yard.”

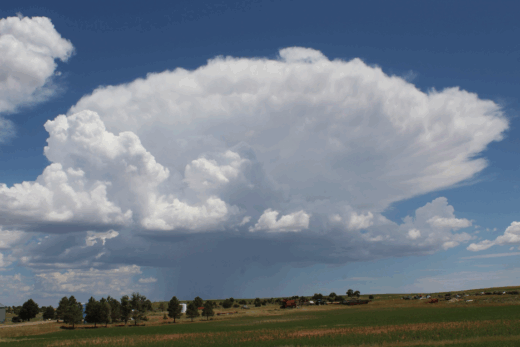

Relatively sprawling and expansive, Southern California’s coastal plains served as perfect foundations for the pavement that was stretching from the beach to the base of the mountains. As LA’s urban heat island developed into a massive urban heat basin, local and then regional microclimates warmed by at least a few degrees. Place your hand near a paved surface on any sunny afternoon or try walking barefoot across the pavement on a summer day: you will quickly sense the additional heat that now radiates through every California urban landscape. Now follow the trails into nearby undeveloped hills covered with the natural plant communities that existed before our pavement: Evapotranspiration from Mediterranean grasslands, coastal sage, chaparral, and oak and riparian woodlands keep afternoon temperatures noticeably cooler. You can also compare the hot paved surfaces to the relatively cooler afternoons common to our city parks or beneath the street trees that decorate our precious urban forests. Further proof of how pavement transforms microclimates is found in research showing how urban heat islands have become particularly extreme even across car-dominated desert cities such as Phoenix and Las Vegas, after the natural soils, cacti, and other desert scrub communities are covered by expanding suburbs. I examine these changes in more detail in my California Sky Watcher book, which will appear in a few months, published by Heyday.

By contrast, you can also sense how the San Francisco Bay Area has evaded some negative effects of our car culture. Constricted on its bumpy little 49-square-mile peninsula, San Francisco was built and cast in the 1800s without cars; and its steep, narrow streets show it. The famed cable cars, streetcars, and hostility to automobiles stand out to this day as if The City were showcasing its antithesis to LA. Beyond The City, the Bay Area’s physical geography helped drive growing differences and perceived divisions between Northern and Southern California. Enormous water bodies separated spreading megalopolises and obstructed potential freeway routes that would have otherwise connected them. Limited car lanes were directed and merged toward the few exorbitantly-expensive bridges that acted like hourglasses; the flowing traffic had to be squeezed into narrow funnels that opened toward urban landscapes on each end of a bridge. The Bay Area’s combined hilly terrain, giant bays, and other assorted and dramatic natural landscapes concentrated populations, restricted where freeways could be built, and forced other ways of imagining transportation and daily commutes.

From the 1960’s and 70’s and beyond, car troubles were emerging from the paved horizon and they impacted more than our urban landscapes. Exhaust that belched out of millions of vehicles without pollution controls began literally choking Californians to death, emboldening air quality management districts to exert their growing powers. Folks who didn’t develop lethal respiratory illnesses still felt the pain of ozone and other air pollutants originating from dirty vehicles. The problems were realized by kids like us who struggled to get a breath while participating in competitive sports and other recreational activities. We didn’t know that we would damage our health when exercising in smoggy air that was twice as polluted compared to today.

Like most adventurous California teens at the time, road trips for me meant escaping to the freedom of new places and open spaces. And the list of magical places to visit and experience grew as my mental maps expanded. I started driving when I was 16 so that I could get to my part-time blue-collar jobs and save some money that would lead to more independence and the great outdoors. I bought my first junk car with that money before graduating from high school. “Get your motor runnin’, head out on the highway” became a theme song for this new-found freedom as long as I could keep my car from breaking down. I tuned in my car stereo and turned up the volume to overcome the roar of wind whooshing into my open windows and past my ears as landscapes raced by and more distant and exotic places called out. What a rush! At last, I was free to break away and both figuratively and literally blaze my own trails. Fantastical vistas and the most remote trailheads were finally within my reach.

Back then, new freeway and road traffic flowed relatively freely compared to today. Global warming and anthropogenic climate change and crushing traffic gridlock had not yet entered into the public discourse. The expanding freeways and additional lanes to everywhere began resembling massive arteries and veins that gradually narrowed into capillaries to feed commuter traffic into more distant communities. When my unreliable clunker was working properly, I could smoothly zip between my jobs and college classes. I occasionally slapped my class notes on my steering wheel to cram study time into my drive time. Once, suffering from sleep deprivation and carbon monoxide poisoning from all the car exhaust, I dosed off while driving on the freeway. I woke up at what seemed to be nearly a mile later, still in my lane, stunned to realize how my steady foot on the accelerator kept my car pacing the steadily-flowing traffic. This was, literally, a car culture wake-up call that I wouldn’t forget. I realized how fortunate I was to be alive and free to make it to my job and classes that day among all the car-commuter madness. You would certainly not survive such an experience in today’s traffic that is constantly stopping and reaccelerating within much narrower lanes.

And then the traffic monster raised its ugly head. During car culture growth years, if a freeway or road got too crowded, we widened it or built another one. But the throngs of new arrivals and commuters would quickly pack the new lanes until we had to build another and then another until we began running out of places to build them and neighborhoods that would allow them. “Rush hour” commutes expanded to two or three hours for some. And so we developed dysfunctional love-hate relationships with our cars and I shared those feelings even though my commutes were never that long. As we worked our way into the final years of the last century, many commuters found themselves trapped by the very car cultures and suburban lifestyles that were supposed to liberate them. Those who couldn’t afford to move closer to their school and work were stuck in gridlock, wasting away both physically and mentally in their nearly stationary cars, poisoned by the high concentrations of air pollutants surrounding them.

For too many Californians, today’s car culture represents an inefficient loss of precious time and a deteriorating quality of life and health. Bay Area commuters have settled as far away as Stockton and other relatively inexpensive Central Valley locales. Thousands of daily commuters into the LA Basin come from more affordable lnland Empire and high desert communities. Many of them drive up to two hours to their jobs in the mornings and then another two hours back home in the evenings. Living around relatively affordable Bakersfield and working in LA County job centers has become a lifestyle for some. Residents around other growing conurbations (such as the state’s second-largest city, San Diego, and in Sacramento) have watched with trepidation over the years and revolted with movements earning names such as “Not Yet LA.” Yet, apparently irresistible car culture momentum has also overwhelmed many of those communities to commit what critics consider the same old mistakes while expecting different outcomes. Look at the gridlock that builds each weekday afternoon as commuters check out of their jobs near the coast and then cram onto freeways, jamming all lanes that point inland, toward more affordable eastern San Diego County suburbs. Listen to the sometimes-daunting daily traffic reports reverberating from Sacramento and every other major California metropolis when serious injury and fatal accidents block lanes here and shut down freeways there. The lucky ones just get stuck in traffic gridlock behind each incident. For the least fortunate, their beloved (or hated) cars turned on them to become violent high-speed killing machines when seat belts, air bags, and other safety features weren’t enough to stop the carnage.

The car-culture momentum balloon started deflating decades ago in some of our major cities, partly because it became too expensive and destructive to rip up neighborhoods and make way for more cars. You could argue that the revolt began way back in the 1970s when the San Francisco Bay Area committed to building and supporting efficient public transportation systems such as BART. I was a beneficiary of those attempts to get people out of their cars. When I moved to densely-packed San Francisco, it was like landing on another planet or in the Land of Oz. I quickly learned that trying to maneuver my manual transmission (AKA a clutch) while frantically bobbing my car up and down the steep, narrow streets was asking for stress and trouble. And it wasn’t necessary. So, I would leave my junky car behind for days and effortlessly ride safe and efficient buses, streetcars, and BART, with no worries about parking or traffic. And I got frequent free entertainment from the circus-like cast of characters that would unexpectedly appear on all the different public transit options. My car came in handy when leaving The City for one-day adventures over the Golden Gate Bridge to the Marin Headlands, Mt. Tam, Muir Woods, Pt. Reyes, Stinson Beach, or to points south such as Santa Cruz Mountains haunts like Big Basin Redwoods, or the scenic beaches around Pescadero, Año Nuevo, Davenport, and Santa Cruz. The car was discarded and convenient public transportation embraced during weekdays to get to graduate school and work, but the car was cherished during weekends. I’ve been the fortunate one to live, work, and play in the best of both transportation worlds.

The Bay Area’s anti-automobile movement was bolstered by the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that badly damaged or destroyed elevated two-level portions of the Embarcadero and Central Freeways. Instead of replacing them, City residents successfully fought to reclaim their views and neighborhoods. The results are seen as today’s unobstructed spectacular views of the Bay from the Embarcadero and in the parks and other public spaces along Octavia Boulevard, landscapes that were previously sliced, blocked, and dominated by massive freeway structures. During this revolutionary period, San Francisco’s late poet laureate, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, famously expressed the growing popular frustrations: “What destroys poetry of a city? Automobiles destroy it, and they destroy more than the poetry. All over America, all over Europe in fact, cities and towns are under assault by the automobile, are being literally destroyed by car culture.”

In contrast to stereotypes, Los Angeles and other parts of Southern California have also recently rejected some new freeways. It may be no surprise that the once-proposed Beverly Hills Freeway (which would have cut through some of the wealthiest communities in the state) was scrapped decades ago. And the last freeway to slice through densely-populated LA Metro neighborhoods was the 105 (Century Freeway), completed in 1993, costing more than $2 billion. Today, giant billboards advertising personal injury law firms soar over this freeway and its working-class neighborhoods that didn’t have the power to stop such a divider. But more recently, South Pasadena and surrounding communities finally blocked the long-planned extension of the 710 Freeway that would have bifurcated their neighborhoods.

And just a few years ago, after long and bitter battles, activists managed to save beloved Trestles surfing beach and San Onofre State Beach (near the border between San Diego and Orange Counties) from a massive toll road. New highways and freeways are still being proposed and debated farther out in Inland Empire and high desert exurbs, complete with the familiar clashing pro and con players fighting to gain momentum and win the hearts of residents, business leaders, and policymakers. Similar battles over what to do about cars continue in inland exurbs beyond the Bay Area that extend well into and through Central Valley cities. They pit car-friendly traditionalists, motivated by growing traffic and commuter crises, against those who see what has happened to larger conurbations closer to the coast and want to preserve what remains of the places and environments they cherish.

We must pause to pay homage here to some of the most offensive monuments demonstrating how we, in our desperation, torture ourselves when we are forced to crowd together with our cars: parking structures. Yes, multi-level parking structures save precious urban space for other activities and they decrease the extent of paved surfaces compared to sprawling parking lots. But once inside a monotonous parking structure, have you noticed that you could be anywhere at any time? It is difficult to imagine how we could build more generic and dull environments. Not only do the different sections and levels all look the same in one structure, but they look and feel no different in cities and suburbs hundreds of miles away. There is just no “there” there. As soon as we enter the gates, we lose our sense of time and place and become disconnected from the unexpected surprises waiting for us in the outside world. Day or night, rain or shine, who cares? We are suddenly surrounding by bland concrete surfaces in every dimension, as if stuck in a Twilight Zone existence. But we are forced to tolerate this loss of precious quality time and sense of place so that we can reach our desired destination, which could be government or business offices, or a clinic, college class, sporting event, amusement park, concert, store, theater, or some other mall-like experience. You can’t be blamed for suffering from a case of claustrophobia while hunting for a space to squeeze your car in to and then walking through these hardscape labyrinths. And don’t even dare start wondering what might happen during an earthquake or fire. The insults to the senses multiply when impatient drivers honk their horns and compete for the closest space and when cheap car alarms are activated to echo among the other commotions … parking structures quickly devolving into unnerving peace stealers. “It’s not a walk in the park” is the understatement for such experiences, which makes one wonder why we don’t demand better from the people who design, build, and maintain these scars on our landscapes and psyches. How about adding, at the least, a few more colorful murals or other displays of art and humanity?

As we progress through this century, you will notice valiant efforts in nearly every city to get people out of their cars. They include innovations in telecommuting, building more affordable housing near schools and jobs, and funding and encouraging the use of public transportation and safer pedestrian and bicycle right-of-ways. As example, several California cities are fishing for more resources to fund light rail and that includes new lines that are stretching across the LA area. Meanwhile, according to Public Road Data from the State of California, we now have more than 175,000 miles of maintained roads in the Golden State, with about 400,000 lane miles. The more than 14 million registered automobiles and 31 million total registered vehicles travel more than 330 billion miles each year on California roads. And according to the California Office of Traffic Safety and CHP in 2022, around 4,000 people (and 1,100 pedestrians) are killed in hundreds of thousands of accidents that result in hundreds of thousands of injuries on our state’s roads every year. We see every day how cars, and the infrastructures and landscapes we have built to accommodate them, are suddenly or in the long-run impacting all of us whether we like it or not. Even in many remote locations, the very same vehicles that give us access to the great outdoors are interrupting the peace and wild landscapes we cherish. Our bipolar love-hate relationship with cars intensifies.

And isn’t it fitting that debates about cars have become just as polarizing as most political debates these days? Listen to the advocates (often on the political right), who mostly celebrate traditional car cultures, life in the suburbs and exurbs, and the perceived libertarian independence that accompanies such lifestyles. You’d think that cars were sent to us from heaven above. And for those living in the most rural and remote regions of the state, cars and trucks continue to represent necessary tools for survival. By contrast, listen to the pundits on the opposite side (often from the political left and clustered in our urban centers) echo the criticisms and sentiments of the late revolutionary writer Lawrence Ferlinghetti. You’d think cars were instruments of the devil.

What are your experiences with and views about cars? Do you think they represent freedom and independence or are they killing us and destroying California lives and landscapes? A little of both? I’ve chased the California Dream across our state on foot, on my bike, in my car, and on all types of public transportation; and I’ve been fortunate to have lived and learned from all of these experiences, celebrating in and sometimes suffering from very different transportation worlds. But I’m also now fortunate to live in a city (Santa Monica) where I have transportation options that include hopping on my bike and pedaling in almost any direction along our many relatively safe bike routes. Our ability to build bridges and pathways toward a brighter and more efficient transportation future depends on a better understanding of the important rolls all of these options (and that includes our traditional cars and newer EVs) have played and will play as we attempt to steer toward better living and working environments.

View this animation illustrating how roads were paved across much of celebrated car-culture poster child LA County until there was no more room for them. The authors suggested that demand on those roads has been growing for nearly 40 years as more cars were crammed into limited transportation infrastructures. Check out their other maps showing historical growth in LA County.

Here are some traditional maps showing major California highways.

And: https://www.tripinfo.com/maps/ca

This impressive interactive GIS site classifies our highways and roads. You can click to choose a wide range of valuable information related to this story.

Finally, as a bonus for navigating through this story, you are invited to breeze through the following colorful photo essays that showcase classic California cars and transportation landscapes. The first set (click to page 2) skips around California’s landscapes made for cars and some that have rejected cars. The second set (click to page 3) celebrates various classic cars that I have recently photographed to illustrate some of California’s car art and culture history.

Thank you for a great essay about cars and California! I’m looking forward to the day when driving won’t be a necessity of life in L.A.