As the death toll rises to more than 130 and scores are still missing in the July 4, 2025 Texas flash flood, at least three questions haunt us: Why did this happen, how could it have been prevented, and could it happen in California?

Made for Flash Floods

Some basic knowledge of the region’s geography and weather patterns helps us answer the first question. Headwaters of the Guadalupe River Basin are perfectly positioned in a region already known as “Flash Flood Ally”, within a sprawling swath across central Texas extending both west and northeast of Austin. The Guadalupe River flows toward the east and curves southeast for nearly 250 miles in a relatively narrow drainage basin from its headwaters, starting in Hill country and the Edwards Plateau west of Kerrville, spreading onto its floodplain, and finally spilling into San Antonio Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Average annual precipitation in Hill Country is about 30 inches. Average July precipitation is just over 2 inches, sandwiched between May/June and Sep/Oct peaks. (Average annual precipitation in Texas varies from 10 inches near El Paso in the far west to 60 inches around Houston in the far east, which leaves this targeted region midway between the state’s contrasting dry and wet climates.)

The surrounding Edwards Plateau is underlain by limestone rock formations and thin soils with infiltration capacities that can be quickly overwhelmed by occasional high-intensity rainfall events experienced in these parts of Texas. Sheet flow down the hillsides is rapidly concentrated into narrow channel flows at the bottom of the slopes. According to the USGS, “The Guadalupe River Basin is relatively long and narrow, with a length of approximately 237 miles and a maximum width of about 50 miles. The basin has a drainage area of approximately 6,700 square miles (mi2).” The entire basin has been growing in population to over 600,000. But those headwaters in that steeper northwestern part of the basin are most prone to flash flooding.

Texas flash flood events often begin in the Gulf of Mexico, where ocean water temperatures soar above 80°F during summer months. Such warm water evaporates into warm overlying air masses that have a high capacity to hold water vapor. (Dew points as high as 80°F are sometimes recorded along the Texas coast from summer into fall.) Those air masses are not only full of water, but are charged with tremendous amounts of stored latent heat, waiting to be released when the vapor condenses to form clouds. The muggy air columns often swirl inland into Mexico or directly into Texas, sometimes imbedded in tropical disturbances.

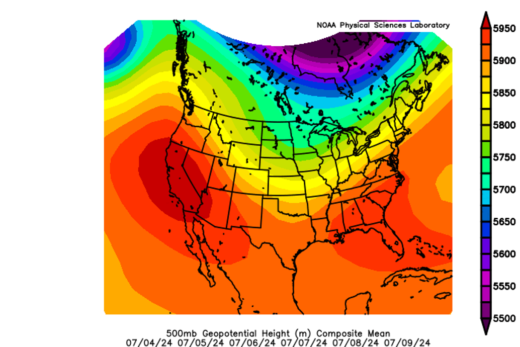

That is exactly what happened during the recent flash floods. After Tropical Storm Barry moved over land and dissipated above the Mexican highlands, its moisture teamed up with additional remnant moisture drawn in from the warm East Pacific (from the other side of southern Mexico). The juiced-up air mass drifted north and became concentrated in pockets caught in a weak unstable low-pressure circulation that stalled over central Texas. Summer surface heating and additional forced lifting up the Edwards Plateau in what is known as Hill Country (which rises up over 3,000 feet) provided the extra instability necessary to build towering severe thunderstorms and local torrential cloudbursts.

The National Weather Service forecast this general pattern days ahead of time and even issued flash flood watches for the region, but these were not the kind of steady and widespread precipitation events common to weather fronts or tropical storms. Many regions of Texas (and some near the worst flooding) received little or no rain, leaving those residents to wonder what was the big deal. Every local Texan has experienced this typical convective summer hit-and-miss instability. Forecasters can warn of scattered thunderstorms and severe weather, but forecast models can’t precisely pinpoint which exact hill or neighborhood will receive the drenching until the local event becomes imminent. Still, NWS tools that include increasingly accurate high-resolution models helped to forecast and follow the massive mesoscale convective system that was developing. Rain rates up to 2-4 inches/hour and local storm totals of 6-8 inches were forecast, though one spot would eventually receive up to a foot or more. Alerts were elevated to flash flood warnings hours ahead as storm locations and severities became more apparent. When individual storms further strengthened and threats increased, wording in the screeching flood warnings became more urgent and desperate, heightened to considerable elevated risk, and finally to a flash flood emergency, which is very rare. (Note the summary of these warnings at the end of this story.) But the communication didn’t make it from the NWS to the victims.

Gravity took over from there, driving cloudbursts on to the sloping surfaces; sheets of water from above landed to become sheet flow headed to the nearest rill or gully. Within minutes, headwater tributary channels that slice through Hill Country served as efficient conduits as they converged to deliver copious streamflow downhill into the Guadalupe River. Depending on the location, river levels are estimated to have increased from a mere trickle to over 25 feet in less than an hour.

Holiday camps were filled with visitors and some locals who were either out of range of the warnings or had temporarily discarded their phones to celebrate their peaceful weekend in nature. The apparent lack of weather radios and absence of sirens exacerbated the dearth of emergency information, leaving oblivious and vulnerable locals and campers in the dark until the floodwaters were surging around them and it was too late; victims didn’t even have time to make the 5- or 10-minute walk up to higher ground that would have saved them. Hundreds were first stranded and then swept away in another definition of the perfect storm. As the hours passed, peak Guadalupe River floodwaters raced downstream, but passing by populations that were receiving the warnings. Scores of upstream victims, who were incorporated into the cascading flood debris, may never be found in the massive downstream deposits. It seems somehow appropriate that, after being caught in reservoirs and behind dams, the Guadalupe’s floodwaters are headed back to the Gulf of Mexico where all this started, perhaps to evaporate again and continue the hydrologic cycle, or even to fuel the next flash flood event.

Learning from Our Mistakes

There is always a lot of finger-pointing following a disaster such as this. For instance, poorly informed individuals have even been misled with misguided stories about cloud seeding. But cloud seeding efforts have been shown to—at best—increase precipitation from preexisting rain clouds by up to 10%, while no additional precipitation is often the result. And the only company (Rainmaker) that was seeding up to a hundred miles away halted its operations two days before the storms hit. As more information pours in (and it is always easier to second-guess as Monday-morning quarterbacks), what at first seemed to be a tragic and unavoidable series of events may have been averted with some simple precautions: by making sure the camps had access and paid attention to emergency warning systems. A few functional weather radios and/or a siren (such as the one installed just downstream) may have saved hundreds of lives. Relocation of the camps slightly uphill from their previous locations and farther from the riverbed will likely be a future remedy. After all, the greatest number of lives lost were in the epicenter of “flash flood alley”, in the heart of the state that averages the greatest number of flash flood victims each year.

While it has earned our attention, this heartbreaking event represents a motivating opportunity to reevaluate where we develop on floodplains and where we live and set up camp to make sure we aren’t the next victims. And if we travel beyond communication range of the outside world, a good map and some simple research ahead of time could determine whether or not we return safely to share our adventures. It is also an opportunity to recall that for every one-degree Fahrenheit increase in temperature, our atmospheric sponge has the capacity to hold 3-4% more water vapor. In a world of increasing temperatures and hydroclimatic whiplash, what goes up must eventually come down, and this helps to explain why severe rain events and their floods are becoming more common: our atmosphere is loading with greater amounts of water and energy that must be distributed. Meanwhile, we are compelled to ask if such a tragedy could happen in California.

Are Californians the Next Victims?

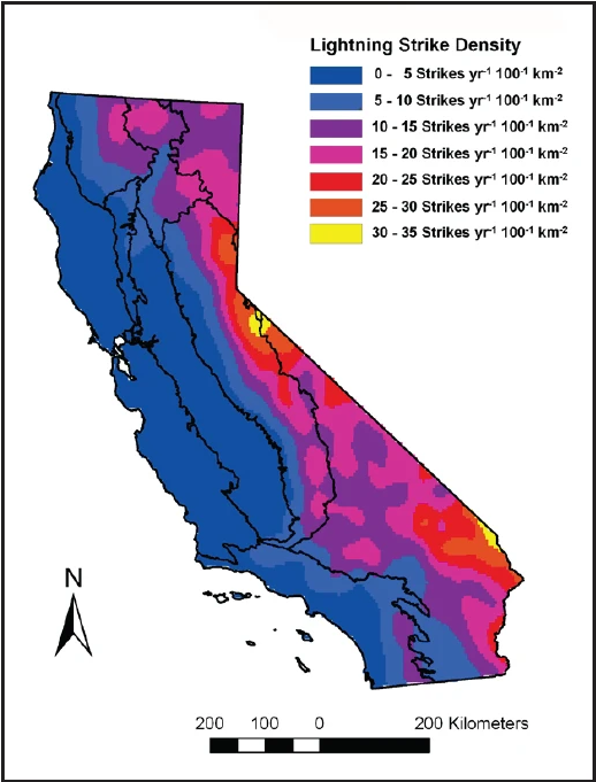

It is a bit ironic how both Texas and California exhibit landscapes that suffer from long periods of debilitating drought, punctuated by torrential downpours and catastrophic flash floods. Within hours in both states, concerns about over drafting groundwater resources, lowering water tables, and dried-up springs turn to saving victims from dangerous flooding. Our Golden State harbors a wide range of flash flood environments, especially after fires strip off protective vegetation. All 58 counties have experienced some sort of severe flooding. Look for steep slopes and a lack of vegetation in places that receive sporadic precipitation and you are in flash flood country. Add loose materials weathered on those slopes, and you are in mud and debris flow country. You will find them scattered across the southwest states and you will hear about the latest unsuspecting victims that were swept to their deaths. I have experienced my share of these violent events and I wrote about a few of them in my California Sky Watcher book. I even started my academic career by studying their impacts on landscapes around the White Mountains along the California/Nevada border. But the conditions that lead to our flash flood events are usually quite different from Texas.

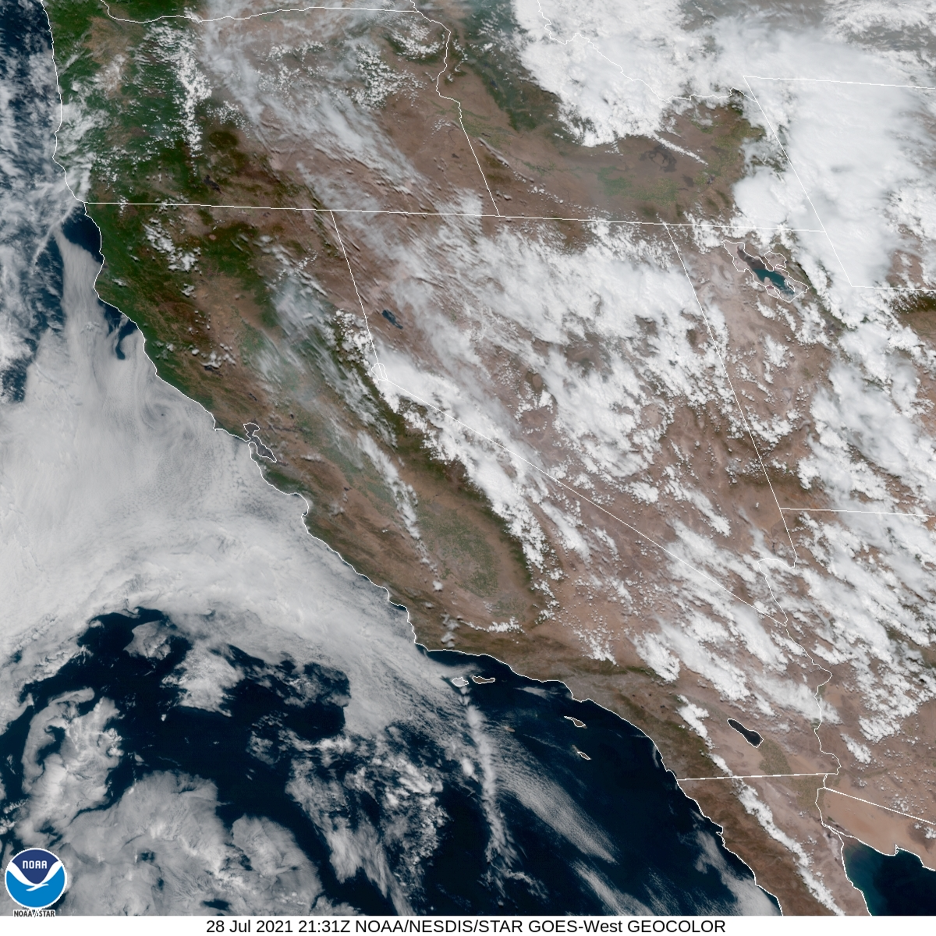

During our southwest summer “monsoon”, we only occasionally get incursions of warm, moist air masses from Mexico. Our summer moisture usually sneaks in from the Sonoran Desert or the Gulf of California rather than directly from the Gulf of Mexico, mainly impacting our inland mountains and deserts. Check out our website story from my storm chasing a few years ago. During late summer, rare tropical disturbances (check this video) might even drift up into California (such as Hilary in August, 2023) as they die out. But our “monsoon” airmasses hardly ever arrive as charged up as those Gulf of Mexico surges into Texas. So, our summer thunderstorms are usually more isolated and less severe, producing very little summer rain on the average, even in our desert and mountain areas.

These towering storms are more like afternoon and evening oddities that must build and maintain themselves above smaller specific watersheds in order to power localized flash floods and debris flows. But their rarity is also what makes them dangerous, when they unexpectedly pop up and generate violent flows that can briefly submerge canyons and cough out material on to alluvial fans before spreading into adjacent valleys. Partly cloudy with a chance of scattered afternoon thunderstorms, and a high of 105 or more, can suddenly turn into a violent two-inch cloudburst and deadly flash flood within an hour.

The aprons of alluvial fans that stretch out from the base of our inland mountains, particularly across Southern California and into the Basin and Range, are made of successive mud and debris flows, recalling thousands of years of rare but violent floods that charged out of individual drainage basins long before our developments and infrastructures covered them. On average, these summer events become wetter and more frequent as we travel east into Arizona and New Mexico. Much of the desert southwest east of the Colorado River experiences peak annual rainfall during the summer months. That is why rangers and other officials close some trails in places such as the Zion Canyon Narrows when hit-and-miss storms erupt into the forecast.

California’s greatest floods are usually associated with our winter storms’ atmospheric rivers. In contrast to the Texas summer downpours, these larger systems that sweep off the Pacific are forecast long before they come ashore so that we can prepare for them, they bring widespread rain and snow, and they may hang around for days. But the danger and damage can easily exceed many billions of dollars as flooding ravages multiple drainage basins, tests our dams and other flood control infrastructures, and spreads across hundreds of square miles of floodplains after spilling out of surrounding mountains.

California’s most powerful series of atmospheric rivers and resulting megaflood (December 1861 – February 1862) not only lasted for more than a month, but inundated many of our lowlands, including the Central Valley and Los Angeles Basin into Orange County. This event is used as an example for what researchers call the ARkStorm (Atmospheric River 1,000), which is likely to return to do more damage than “The Big One”, the massive earthquake that is overdue along the San Andreas Fault Zone. As examples, floodplains along the Yuba, Russian, and Pajaro Rivers, most rivers pouring out of the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada, and most of the Central Valley and Southern California coastal plains are all at risk. Intense downpours that become imbedded in atmospheric rivers and move over burn scars have also powered scores of local mud and debris flows, such as in Montecito in 2018, which killed 23 people. So, we can certainly learn from the Texas tragedies, but we are certainly not Texas (interpret as you wish).

What we share with Texas are the increasing amounts of moisture and energy in our atmosphere, warning us how such extreme events are becoming more likely each year. Instead of building developments in harm’s way, we can prepare by leaving spreading basins open at the base of our mountain ranges to catch runoff and allow the pooled water to gradually soak into our aquifers. We can also build more debris basins at strategic locations along water courses to catch debris flows before they invade our settlements and destroy infrastructures. We also share serious concerns about how recent budget cuts and layoffs at NOAA and the National Weather Service will lead to the unnecessary loss of life and property in the future. Let’s all hope that we will be smart enough to prepare for the coming extreme weather events so we won’t have to write future stories about similar tragedies in California.

Continue below to find some additional sources and a timeline of the Texas flood warnings.

Relevant links:

Guadalupe River Rainwater Harvesting

From InFRM: Interagency Flood Risk Management/USGS

Daniel Swain Video at Weather West

Some California Links:

Note how the first two videos look hauntingly similar to the Guadalupe, Texas flash flood.

The Whitewater River flooded after Tropical Storm Hilary (August, 2023) dropped torrential rains on the San Bernardino Mountains.

Here’s dramatic video showing what resulted when a relatively warm atmospheric river dumped heavy rain on low-elevation Sierra Nevada snowpacks (March 10, 2023), all part of a series of deluges that eventually broke California’s twenty-plus-years megadrought.

A Story about the Megaflood of 1862 and preparing for another.

Burned Watershed Geohazards from the California Department of Conservation.

Central Valley Flood Protection Plan

National Weather Service Budget Cut Impacts

Late July Update: Summer monsoon thunderstorms continued to generate flash flooding across New Mexico into late July, 2025. The mountain village of Ruidoso was repeatedly flooded when heavy cloudbursts poured over upstream burn scars. Here are just two examples of videos floating around out there.

Here is a summary (from media sources) of some emergency warnings from the National Weather Service leading up to and during the Guadalupe River flash flood event:

Thursday, July 3

The National Weather Service had issued several flood watches for counties in central Texas on Thursday, July 3, warning of the possibility of rain and flash flooding through Friday, but these were not emergency alerts.

11:41 p.m., Bandera County — NWS sends a warning about potentially “life threatening” flash flooding of creeks and streams for residents of central Bandera County, the neighboring county to the south of Kerr County and Camp Mystic. The message includes some standard NWS flash flooding language: “Turn around, don’t drown when encountering flooded roads. Most flood deaths occur in vehicles. Be especially cautious at night when it is harder to recognize the dangers of flooding. In hilly terrain there are hundreds of low water crossings which are potentially dangerous in heavy rain. Do not attempt to cross flooded roads. Find an alternate route.”

Friday, July 4

1:14 a.m., Bandera and Kerr Counties — This message, the first one for Kerr County, included some of the same standard NWS flash flooding language as the warning sent to Bandera about an hour and a half before.

1:53 a.m., Bandera County — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier first warning to Bandera County (but not Kerr).

3:35 a.m., Bandera and Kerr Counties — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to the two counties, but in the warning language it adds: “It is important to know where you are relative to streams, rivers, or creeks which can become killers in heavy rains. Campers and hikers should avoid streams or creeks.”

4:03 a.m., Bandera and Kerr Counties — This NWS message, covering the area that includes Camp Mystic, repeats much of the earlier message but is the first to add this more urgent wording: “This is a PARTICULARLY DANGEROUS SITUATION. SEEK HIGHER GROUND NOW!” and “Move to higher ground now! This is an extremely dangerous and life-threatening situation. Do not attempt to travel unless you are fleeing an area subject to flooding or under an evacuation order.”

4:03 a.m. — The National Weather Service in Austin/San Antonio issues a Flash Flood Emergency, stating: “At 403 AM CDT, Doppler radar and automated rain gauges indicated thunderstorms producing heavy rain. Numerous low water crossings as well as the Guadalupe River at Hunt are flooding. Between 4 and 10 inches of rain have fallen. The expected rainfall rate is 2 to 4 inches in 1 hour. Additional rainfall amounts of 2 to 4 inches are possible in the warned area. Flash flooding is already occurring.”

5:34 a.m., Kerr County — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to Kerr County, which includes Camp Mystic. “This is a FLASH FLOOD EMERGENCY for the Guadalupe River from Hunt through Kerrvile and Center Point. This is a PARTICULARLY DANGEROUS SITUATION. SEEK HIGHER GROUND NOW!” and “Move to higher ground now! This is an extremely dangerous and life-threatening situation.”

6:06 a.m., Bandera and Kerr Counties — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to both counties. It reads in part: “Local law enforcement reported numerous low water crossings flooded and major flooding occurring along the Guadalupe River with rescues taking place. Between 5 and 10 inches of rain have fallen. Additional rainfall amounts up to 2 inches are possible in the warned area. Flash flooding is already occurring. This is a FLASH FLOOD EMERGENCY for South-central Kerr County, including Hunt. This is a PARTICULARLY DANGEROUS SITUATION. SEEK HIGHER GROUND NOW!”

6:27 a.m., Kerr County — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to Kerr County, saying “This is a FLASH FLOOD EMERGENCY” and “SEEK HIGHER GROUND NOW!”

The Guadalupe River reached its peak level of about 36 feet at around 7 a.m. Friday, July 4.

7:24 a.m., Kerr and Kendall Counties — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to Kerr County and neighboring Kendall County, to the east. It reads in part: “A large and deadly flood wave is moving down the Guadalupe River. Flash flooding is already occurring. This is a FLASH FLOOD EMERGENCY for THE GUADALUPE RIVER FROM CENTER POINT TO SISTERDALE. This is a PARTICULARLY DANGEROUS SITUATION. SEEK HIGHER GROUND NOW!”

8:47 a.m., Kerr County — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to Kerr County.

9:04 a.m., Bandera and Kerr Counties — NWS sends a repeat of its earlier warning to these two counties.

Several repeat warnings followed, especially for downstream locations, as peak flooding spread southeast out of Hill Country.

The following additional images (you may recognize some from previous stories on our webpage or in my book) illustrate summer thunderstorm impacts in California’s deserts.

THE END

This was very interesting and informative. Speaking of the NWS warnings that didn’t go out to Kerr county until after 3am, I would be interested to know if by the 3:30am warning it was tragically too late. I mean, clearly the warning infrastructure was compromised, how high was the water at midnight? 1am? 2am? 3am? And why did they wait so long to report from 1am -3am to Kerr county?

Really enjoyed the CA section. I can’t even imagine a monsoon in CA. That’s crazy! We can’t even handle a drizzle without an increase in motor accidents in SoCal, let alone 2 month shower. I wonder if our many and various mountain ranges play a bigger role in why we aren’t typically known as flash flood ally. Texas is pretty flat in most places, there isn’t a lot of obstruction like in CA for as big as our state is.

Anyway, thanks for this read. I will have to re-read to get a better handle on it, but you laid it out very well and dare I say, beautifully in some areas. Are you a writer? 😉

Hello Amber:

Just now checking through our comments section on our website and saw that yours got lost among the junk ads. Sorry! But I just added another story, so check it out when yo get a chance. Enjoy what should be a long string of sunny days!

Bill Selby

wselby@smc.edu

https://www.rediscoveringthegoldenstate.com