Forward: An Autobiographical Synopsis

Let me introduce myself. I am a California water drop. I condensed from billions of water vapor molecules in the air above the North Pacific Ocean to become embedded in the clouds that evolved into a large storm system. Through alternating ups and downs, and freeze and thaw cycles, I was carried in a rotating middle latitude wave cyclone as it drifted southeast and toward California. As the storm swept across the Golden State, I was forced to rise higher over the mountains and I grew as a giant ice crystal until I fell as a fluffy-turned-heavy snowflake in the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

After weeks of resting in the snowpack just above 9,000’ elevation, I emerged in the spring thaw, melting into Yosemite’s subalpine ecosystems. I flowed down the slopes under the force of gravity and merged with similar water drops until we accumulated into rivulets that merged into tributary streams that finally joined the Merced River. The river, swelling with spring’s snowmelt, cut through spectacular mountain canyons and valleys and tumbled over waterfalls. After flowing west through Yosemite Valley, I finally glided through the gentler-sloping foothill country and into the Central Valley. After maneuvering through various reservoirs and other human obstructions, I joined the larger San Joaquin River. From there, I flowed northwest on the valley floor and into the storied Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. There, I merged with Sacramento River water and gradually meandered through San Francisco Bay, under the Golden Gate, and back out to sea.

I drifted south in the cold California current and began veering to my right and farther out to sea off Baja, Mexico. Caught in the giant clockwise pinwheel that is the North Pacific Gyre, I turned farther west toward Asia and then north. My saga “ends” where it started in the North Pacific Ocean. But, my story doesn’t really “end” there any more than it “started” there, since I am playing an active role within Earth’s interconnected, perpetual water cycles.

As you follow my path in the more detailed account that follows in Parts I and II, the author will map out the many other routes I could have followed, with suggestions about how other water drops traveled in many different directions to experience their many very different fates. It is a classic California water story.

So, put on your seat belt, enjoy the ride, and don’t forget to show your appreciation, as you may run into me at any time on any day.

Preface: Following the Water and our Story

Here is a story about a drop of water that happened to pass through California during its wild ride within Earth’s great water cycles. As with other visitors to the Golden State, it undergoes many different phases and metamorphoses as it passes through an astounding variety of environments. And similar to other residents of and visitors to California, our water drop cannot remain isolated, as it often interacts and merges with other drops and its dynamic surroundings. This is a captivating story of adventure that alternates from scenes of peace and quiet solitude to extreme turbulence and chaotic violence, all powered by nature. The difference between our drop and your favorite superhero story is that this saga is plausible and our water drop and others like it are having direct and indirect impacts on all of us every hour of every day.

Our story is organized into three parts. The first part (Web Page 1) is mostly a meteorological experience that follows the water as it rides through the atmosphere above the North Pacific Ocean all the way to California and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The second part (Web Page 2) is mainly a hydrological adventure that shadows our water as gravity pulls it down the mountain slopes, into the Merced River, through Yosemite and into the Central Valley, and finally back out into the Pacific Ocean. The third part (Web Page 3) is a sort of glossary that explains some of the more technical terms and concepts used throughout this riveting saga; it is intended to provide you with a clearer understanding of the science behind the story and the scenery. When discussions deserve more detailed scientific explanations, they are flagged with “(E)” and a numbered notation in the text so that you can quickly refer to the glossary in Part III on Web Page 3, where you will find a more thorough explanation that might prove helpful.

Every day, 40 million Californians watch water flow out of their faucets or down their streets or through streams or in to various reservoirs and lakes. They might catch raindrops or snowflakes and then marvel at how water in the soil is absorbed by all the plants and animals around them for essential nourishment. Where did that water come from and where is it going? The mystery unfolds here as we follow a California water drop.

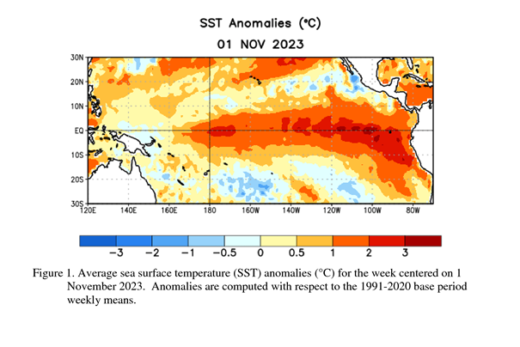

Part I: A Wild Ride to California

It all “started” in the North Pacific Ocean when surface water gained enough energy to evaporate into a passing air mass that was not yet near saturation. Another way to word this is that the air temperature was higher than its dew point temperature, so that the relative humidity remained below 100%; and so the air retained its capacity to hold more water vapor, or water in the gaseous phase (E1). Countless billions of water vapor molecules that added up to tons of H2O were absorbed by this air mass as the total amount of water vapor in the clear air (E2) increased over time. As more water molecules were absorbed, the cooler air parcels eventually approached saturation and a few variable, innocuous clouds began to condense in some of the air parcels at various altitudes in the stable air column.

Then, a very cold, dense, heavy air mass slid east off the frigid Asian continent and over the North Pacific and changed everything. It wedged under our relatively warmer and lighter air column and lifted it, creating instability and turbulence (E3). As our air mass ascended, it quickly cooled to its dew point temperature. Each of the innumerable billions of tiny water droplets organized around water-seeking condensation nuclei known as hygroscopic nuclei and our water drop was no exception. It condensed and grew and successfully competed for available moisture by forming around a tiny, suspended, salt particle (E4). As the slightly salty water drops grew in the saturated air, accelerated condensation released latent heat, adding more energy to the surrounding clouds during the change of state from vapor to liquid water drops (E5). Many of the drops, including ours, began to freeze as they were lifted to higher altitudes where temperatures were well below freezing, releasing a little more latent heat during their change of state, encouraging more vertical development in the clouds.

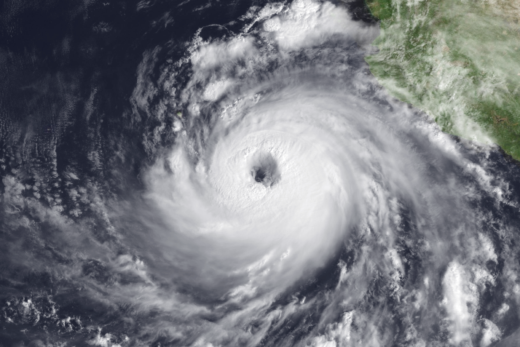

This became an unstable environment where towering clouds were organizing into a massive low pressure system with its rising air masses. The growing storm took on characteristics of a middle latitude cyclone. Our water drop-turned –ice crystal was caught in the winds spiraling into the low in a counterclockwise direction. Stronger pressure gradients pulled the ice crystal’s air parcel toward its left and into the center of low pressure, but the Coriolis effect (caused by the spinning Earth) was simultaneously pulling our ice crystal and its surrounding air parcel to its right (E6). This natural tug-of-war was joined by centripetal and frictional forces that exerted their influence as our ice crystal and its air parcel continued spiraling counterclockwise toward and around the strengthening low pressure storm. It was caught in fierce, gale-force winds as it collided with billions of other water drops and pieces of ice in the clouds. Our ice crystal alternately ascended and froze in updrafts and descended and partially melted in downdrafts; but it never made it to the surface, as opposed to some others that precipitated as snow, sleet, rain, or hail, or others that evaporated into the air before reaching the surface (E7).

Our developing middle latitude wave cyclone was considered to be an Aleutian Low since it originated near the Gulf of Alaska. It grew to more than 1,000 miles in diameter as appendages of warm and cold fronts organized and spiraled around it (E8). Upper level winds began steering the entire system east, toward the West Coast. These powerful high-altitude winds, which peak in a cylindrical core that we call the jet stream, sheared off tons of ice crystals and carried them away to the east from the top of the storm. Simultaneously, more water vapor was being absorbed and incorporated into the base of the storm from the moist environment closer to the surface. Still, our ice crystal/water drop managed to hold together and remain in the storm system. As those upper level winds shaped a deeper longwave trough in the westerlies (E9), the entire system began drifting southeast toward the West Coast. Our storm system was transporting our water drop/ice crystal to California as the wild ride continued.

As the storm approached California’s north coast, its counterclockwise rotation pulled in a plume of warmer, moist air from the subtropics up ahead of it. Our ice crystal was caught near this intrusion and it nearly melted back to become a water drop…until it swung around the low and encountered a colder air mass pulled down from the Gulf of Alaska, freezing it again. Through days of freezing and thawing and growing larger and smaller around that initial microscopic salt particle, racing around the low and across the Pacific with surrounding air parcels, our water drop/ ice crystal had somehow survived. And now it was embedded in a definitive cold front associated with the mother low, all marching across the California coast. It rode in the towering and turbulent cumulus and cumulonimbus clouds of the cold front as it swept down the coast and inland.

As the front carried up and over the Coast Ranges, embedded air masses were forced to rise even faster, creating more instability (E10). Ours became one of the tons of ice crystals that grew larger by accretion in the ascending saturated air until it was so heavy, it fell toward the ground near the Bay Area. Though many other giant crystals landed there just after melting, ours encountered another powerful updraft that lifted it higher into the clouds. It rode these clouds with the cold front all the way over the Sierra Nevada Mountains, where they were lifted even higher, up to 30,000 feet. During this orographic lifting, additional moisture attached to our ice crystal so that it finally grew too heavy (E11). And so it fell into the high country of Yosemite, crunched between tiny air pockets with billions of other snowflakes that may have similar stories (E12).

That winter storm delivered copious amounts of low-elevation rain and high-elevation snow as it swept through northern and central California. Water drops and ice crystals similar to the one we have followed soaked into soils and accumulated on surfaces from the Klamaths and Cascades, to the Coast Ranges and Sierra Nevada, and in the valleys that separated them. The cold front even held together long enough to spread lesser amounts of precipitation into thirsty southern California (E13). But as the upper level trough continued drifting east, the storm and cold front that it carried was forced up over those major mountain ranges. The rising air on the west side of the mountains squeezed out and then dumped most of the remaining moisture there in the form of orographic precipitation. In contrast, by the time the system cleared the peaks and descended down the leeward, or rainshadow, sides of the mountains, it was in disarray and moisture starved (E14). Though some showers would also fall over the mountains of the Basin and Range to the east, our ice crystal had already dropped out over Yosemite, just before the at least temporary demise of this once-powerful Pacific storm system.

Our large snowflake that fell out of the storm that winter night entered a dramatically different environment in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It settled and piled up with billions of other snowflakes and ice pellets into Yosemite’s high country, a place of solitude with a kind of striking calm and quiet that few of today’s humans will ever experience. There were no people for many miles in this mountain wilderness, where even the animals had taken shelter. It was a deafening silence, as the fluffy snow seemed to absorb any sound that dared propagate through this frigid winter wonderland. An occasional clump of snow would fall to the surface from the limbs of a nearby overburden Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) or other tree species in this subalpine forest. Our giant snowflake was eventually buried below layers of other snowflakes delivered from this and subsequent winter storms. Quiet and calm buried in more silence, squashed together, waiting for a warming sun that wouldn’t come for weeks.

But as with the other raindrops and ice crystals that fell across the state during this latest winter storm, there are plenty of surprises, dramas, and excitement to come in our story, as we follow the continuing adventures of this water drop in California.